The true story of the love of an Aboriginal woman

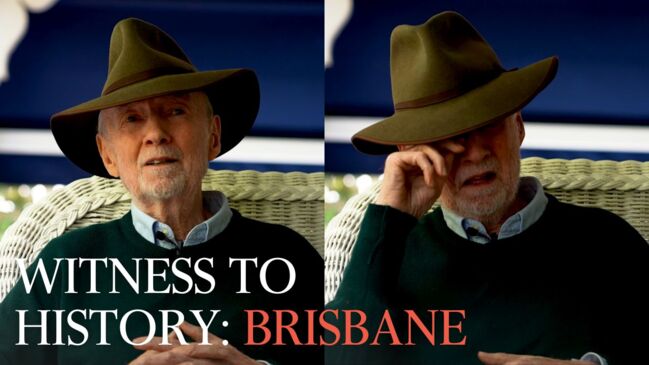

The story of a marriage forbidden revealed systemic racism and led to a life-long connection. For our 60th birthday, Hugh Lunn recalls this touching story.

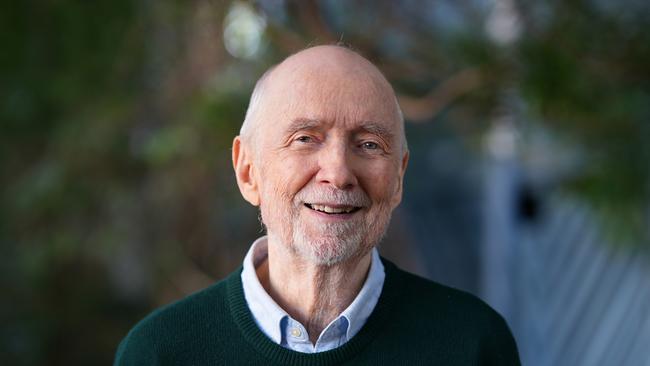

During the 1970s and 80s I was referred to in Sydney as “The Australian’s foreign correspondent in Queensland”. Partly because I’d worked as a foreign correspondent in unusual places such as Indonesia, Vietnam, Red China, Hong Kong and West Papua, but also because Australians see Queensland as another country. A place with stories that could never come from anywhere else.

Like my story about three Indigenous men who were sentenced to 18 months’ jail for killing a cow when their families were hungry. One was almost blind, supporting seven kids under 11, and had no previous convictions. One was supporting 10 children and had not previously been convicted of a similar offence. The third, an 18-year-old unemployed youth, had once stolen poultry worth $20. Their appeal was unsuccessful with three judges agreeing the sentences should stand. Chief Justice Hanger added: “If there were any error in it at all, it was on the light side.’’

So I called my story, Was it a Fair Cow?

This article was photocopied and handed out in Brisbane’s Queen Street. Years later, in 1981, it prompted a public servant to come and see me at The Australian’s Brisbane office. He said the government’s own files showed Aboriginal people being treated even worse.

He wanted to tell someone, and thought I’d be interested.

I replied: “Yes, but don’t use your name. Let’s give you a pseudonym, say … oh … Chris Prince.’’

Months later my secretary, Lee Watters, said: “There’s a Chris Prince on the phone but he won’t say what he wants.’’

Too busy.

Lee left, but came back: “He insists you know him: Chris Prince?’’

“Never heard of him.’’

Lee insisted: “Something’s going on. You should talk to him.’’

I took the call, and the next day picked up two thick files from an agreed spot: just two of the 50,000 files on Indigenous people held by the Queensland government department in George Street.

One was about a young Aboriginal woman who fell in love with a young white man she had met on a steam train in April 1938. Two months later, the man wrote to the Native Affairs Minister, who oversaw the Chief Protector of Aboriginals, asking permission to marry, writing: “We are very devoted to each other.’’

Many more letters and reports followed, until police were sent to investigate if the man had “communist tendencies”.

After years of indecision the couple had a baby. “The baby is very dark,” said a report sent back to George Street. That was enough.

“The marriage is not desirable,” the file concluded.

I tracked down the now elderly woman, living alone in a small fibro home on the outskirts of Toowoomba. When I mentioned the thwarted love affair she became distressed. “How do you know this? No one knows this!’’

I realised, too late, that I should never have interfered in her life. Thus I wrote the article without using her name, although it weakened the story. To protect the identity of the baby boy, I said the baby was a girl.

The story had a huge effect on The Australian’s editor, Les Hollings, who rang to say: “What have we done? What have we done to our Aborigines?”

So I wrote a series of four articles on just what we had done. The thwarted love story was only one example.

After the woman’s story appeared, she turned up in my office dressed in gloves and a hat, saying a movie should be made starring her niece.

It almost happened.

When they saw my story, a Griffith University student film unit filmed the niece on an old train, and interviewed the woman and me. But their work disappeared when someone taped over the video!

Years later, I arrived home to see a large Indigenous man my age sitting in the dark on my front steps, waiting.

I somehow knew it was the baby boy. What could he want? University of Queensland Press had published my story in a book, Queenslanders. Could I sign a copy?

Two years later he was back on my steps again. This time, his mother was dying in the Princess Alexandra Hospital. I offered my condolences but he replied: “You don’t understand. You have to be there for her death because you told the story of her life.”

At the hospital, a dozen relatives filed silently out of the room without looking at us. Although semi-comatose and sweating profusely, this woman – who had been stopped in ripe life from marrying her sweetheart, the father of her only child, the man she still loved – held my hand as her baby boy wiped her brow, telling her: “He’s here, Mum. He’s here now, the man who told your life. He’s here.”

As it happened

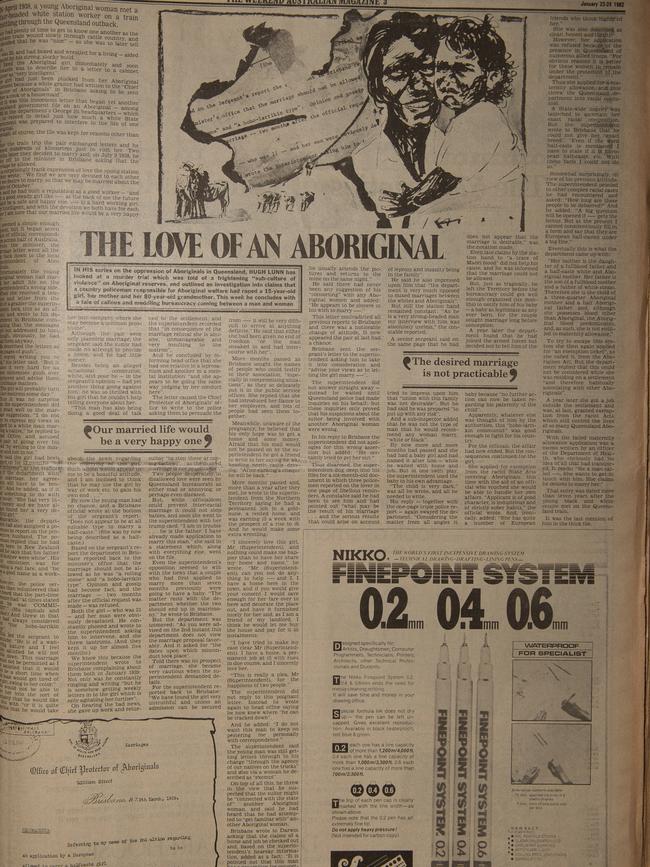

An extract from Hugh Lunn’s story on callous and meddling bureaucracy coming between a man and woman, published January 23-24, 1982

In April 1938, a young Aboriginal woman met a fair-headed white station worker on a train rattling through the Queensland outback.

They had plenty of time to get to know one another as the old steam train wound slowly through cattle country, and she decided that he was “nice” – as she was to later tell police.

He was 25, and had boxed and wrestled for a living – aided no doubt by his strong, stocky build.

He liked the Aboriginal girl immediately and soon afterwards was to describe her in a letter to a cabinet minister as “very intelligent”.

The girl had just been plucked from her Aboriginal settlement because a white grazier had written to the Chief Protector of Aboriginals in Brisbane asking to be sent “either a cook or a housemaid”.

And it was this innocuous letter that began yet another Queensland government file on an Aboriginal – among 50,000 in the department’s George St headquarters – which was to record in detail just how much a white State government was prepared to interfere in the life of one Aboriginal. Though, of course, the file was kept for reasons other than this.

After the train trip the pair exchanged letters and he covered hundreds of kilometres just to visit her. Two months later they decided to marry and, on July 9, 1938, he wrote to the minister in Brisbane asking that the marriage be allowed.

In a surprisingly frank expression of love, the young station worker wrote: “We find we are very devoted to each other and we desire to marry, so that we may be married about the middle of October.”

He said he had built a reputation as a good worker – “and with a good steady girl like ____ at the back of me the future should be a safe and happy one. ____ is a hard working girl, very intelligent, and with the devotion we both have for each other I am sure that our married life would be a very happy one.”

It seemed a simple enough request, but it began seven years of official correspondence across half of Australia.

60th Anniversary Witnesses to history

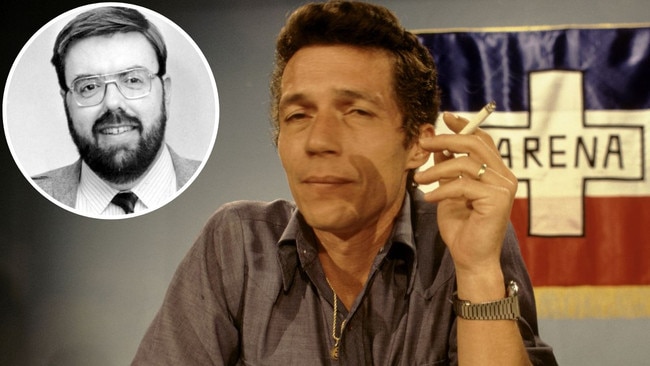

For a journalist, no story comes close to this one

The Australian’s former US correspondent was outside the Capitol on the day an angry mob invaded, urged on by Donald Trump.

Simple instructions: ‘Wear a ballistic helmet and a bulletproof vest’

The kibbutzim might have been tiny villages but they were the model, in miniature, for how a future Israel could have looked next to its Palestinian neighbours. By all rights, our reporter shouldn’t have made it there. But he did.

A large Indigenous man on my porch had an unexpected message

The story of a marriage forbidden revealed systemic racism and led to a life-long connection. For our 60th birthday, Hugh Lunn recalls this touching story.

Inside story: How Osama bin Laden hid in plain sight

The Australian’s then-South Asian correspondent had numerous run-ins with armed Pakistani police while covering the story of the decade. But nothing they could dish out could have been worse than having to tell the editor she’d been kicked out.

Cold, furious: The most evil man I have ever met

Getting to interview this man was challenging. He hated ‘gringo’ journalists and had vowed he’d never talk to one again. All of my peers warned me he goes crazy if you ask him about the death squads. But I had to try.

‘Stop the presses’: breaking the news of new pope

When the wisps of white smoke billowed from the Vatican chimney, The Australian newspaper had long been put to bed. Our correspondent couldn’t wait another day to file. We share this story for our 60th anniversary.

The first big yarn to take a toll on Hedley Thomas

Being sent to cover the bloody overthrow of the communist regime in Romania was a seminal experience for a young reporter who would become one of The Australian’s most highly acclaimed journalists.

At the scene of the story that gripped the world

Reporting from the muddy mouth of the cave complex as a monsoon loomed, it felt crushingly inevitable we would be relaying grim news about a trapped junior soccer team. But then came a sudden turn.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout