The first big yarn to take a toll on Hedley Thomas

Being sent to cover the bloody overthrow of the communist regime in Romania was a seminal experience for a young reporter who would become one of The Australian’s most highly acclaimed journalists.

It is a few days before Christmas 1989 in London and I’m in a room filled with long shelves for editions of Rupert Murdoch’s newspapers, sent in air-bags every day from Australia.

The Australian has pole position. It is slightly more exalted in its place on the shelves than editions of The Daily Telegraph, The Courier-Mail, The Herald Sun, The Advertiser, The Mercury and The Northern Territory News.

At 22, I must be the luckiest young journalist in the world. Still pinching myself at being transferred from Brisbane to be a foreign correspondent in News Limited’s London Bureau in Vauxhall Bridge Road, Pimlico, a short walk from Westminster.

Technology isn’t TikTok; it’s a fax machine. When it whirrs into action with requests sent by the newspaper editors in Australia, I want to be nearby to snaffle ideas for the most exciting assignments.

The editors send requests like these:

# “Please send 2000 words overnight on how the Queen, Prince Philip, Charles and Diana will spend Christmas.”

# “Can someone do a long read on why everyone in Britain either loves or hates Rolf Harris?”

# “Why is Cat Stevens a Muslim and calling himself Yusuf Islam? Urgently seeking lengthy feature on this leap of faith.”

We believe some of the more dull requests are from editors so riven with envy of our postings in London, they ask for stories likely to put us in our place.

At the time, I briefly and hopefully believe I have this job because I’ve been talent-spotted as a young fellow who might have some potential as a reporter when he grows up.

My bureau colleague James McCullough – The Australian’s late, great and garrulous finance writer – cheerfully sets me straight.

He reckons I’ve been sent because I’m cheap – modest salary, housing allowance of 45 quid a week, and no family in tow. The truth is, I would have worked for nothing to experience the opportunities a posting like this delivers.

My flight to London was only my second trip overseas. The first had come only months earlier – a four-day “junket” to Guam. With such threadbare international experience before I unexpectedly became a “foreign correspondent”, it’s no wonder I suffered gut-wrenching bouts of impostor syndrome.

My fears related to the frequency of bylines in Australia’s newspapers. If I was having a purple patch – something I could influence by grabbing those requests on the fax machine – life as a foreign correspondent was wonderful. A lean period with few bylines led to fears of being “found out”, and of being recalled to Brisbane.

A few days before Christmas 1989, a sensible but risky request rolled out of the fax machine. I grabbed it.

Romania and its hardline Communist Party leadership were unravelling.

There were violent street demonstrations. The downtrodden people wanted their tyrannical ruler, Nicolae Ceausescu, to quit after 24 years of Stalinist dictatorship. Throughout Eastern Europe, communism was in retreat and democracy in early flower. It looked like Romania’s time had come.

The editor in Australia asked: Would it not be a good idea for one of the bureau’s correspondents to go to Bucharest to cover the seeds of potential revolution?

With bureau chief Murray Hedgcock’s sage advice to stay safe, I grabbed a small atlas, trousered a wad of cash from the office safe, copied a folder of clippings about Romania from The Times, and printed all the latest wire stories. They foreshadowed a bloody Romanian Christmas.

The British Airways flight that afternoon put me in Istanbul. I had overshot Bucharest by about 900km. Romania’s borders were closed amid sporadic fighting and a spiral into revolution – this meant airspace was also off limits. As I passed check-in counters and airport screens showing every flight to Bucharest as cancelled, my luck changed. In Istanbul’s chaotically crowded airport, I literally ran into Nicolas Rothwell, The Australian’s brilliant multilingual Europe correspondent and intellectual who had lived out of a suitcase through 1989 reporting from Poland, East Germany, Bulgaria and Hungary as the Eastern Bloc crumbled.

Nicolas appeared happy to see me. Perhaps because he was out of cash after weeks on assignment in Eastern Europe – and I had brought plenty from London. Nicolas organised tickets on a flight to Budapest in Hungary, and negotiated with a driver to take us to the Romanian border.

At every opportunity he tuned into the BBC World Service on his military-grade radio. We heard grave reports of indiscriminate killings. Ceausescu and his loyalists were killing the people in a desperate bid to cling to power.

There was tension and foreboding at the border. A gaggle of American journalists loudly debated their next move. Nicolas and I quietly left after he persuaded a Czechoslovakian Red Cross convoy to take us across the border. Shortly before noon on Christmas Eve in the Romanian town of Arad we boarded a train to the capital, Bucharest.

Through the shortwave radio we kept up with the BBC’s hourly broadcasts. They were grim. There were reports of civilian deaths in the hundreds, perhaps thousands, across Romania’s countryside, towns and cities. In all the places our train was stopping.

I thought about how I had ended up here. What I knew about war reporting could fit on a postcard. I tried to disguise my fear.

As the almost-empty train chugged across Transylvania, we shared bread, cheese and a bottle of Bulgarian wine. We made nervous small talk with our new-found friend, Peter Hitchens, of London’s Daily Express, the brother of Christopher Hitchens.

Fierce battles with civilians and students involving the military and the political police known as the Securitate were being waged in Bucharest where the train would end its journey.

I filed this at the time:

Our train rumbled into Bucharest about 11pm and almost immediately we were surrounded by armed students, most of whom knew somebody who had been killed in the fighting on the streets of the capital.

The dead were piling up in the city’s morgues and hospitals.

The courage of the students, many no more than 22 years old, was uplifting.

Once outside, they put themselves between me and the most likely line of gun-fire as we ran half-crouched towards the Intercontinental Hotel.

Throughout the night, the rat-tat-tat and shelling continued.

On Christmas Day, the brave students led me around the city, past makeshift shrines to the fallen, past patches of snow stained by blood, past the tanks, the headquarters of the megalomaniac Ceausescu, twitchy soldiers, and snipers’ nests, and the charred remains of family cars and houses.

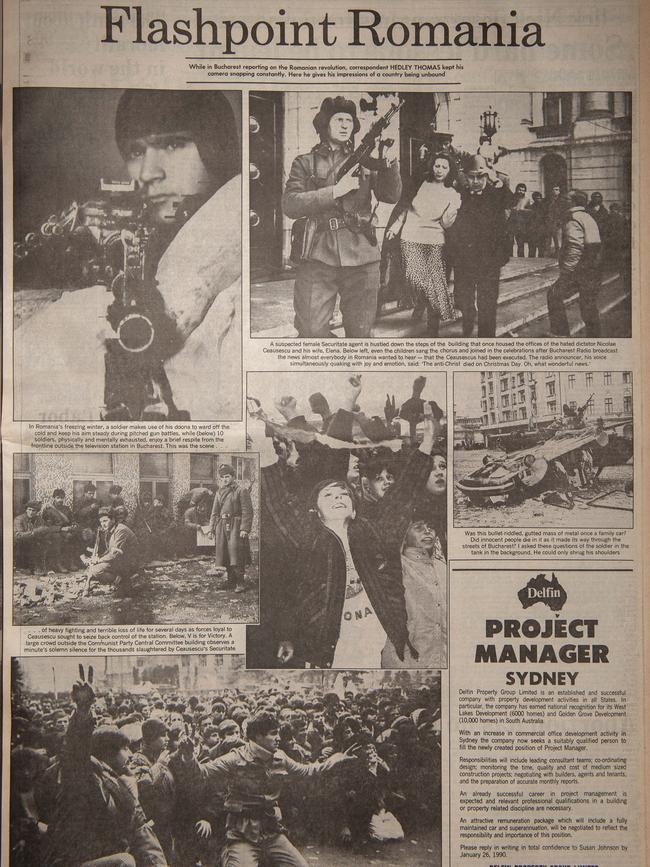

Late in the evening a jubilant announcer on Bucharest radio made a stunning declaration. He said: “The anti-Christ died on Christmas Day! Oh what wonderful news.”

Having lost the military’s support, Ceausescu and his wife, Elena, self-proclaimed father and mother of an impoverished people, were accused of genocide and fraud in a secret trial.

They were executed by firing squad as Elena screamed that her accusers could go to hell. After years of misery, and days of indiscriminate killing, celebrations erupted.

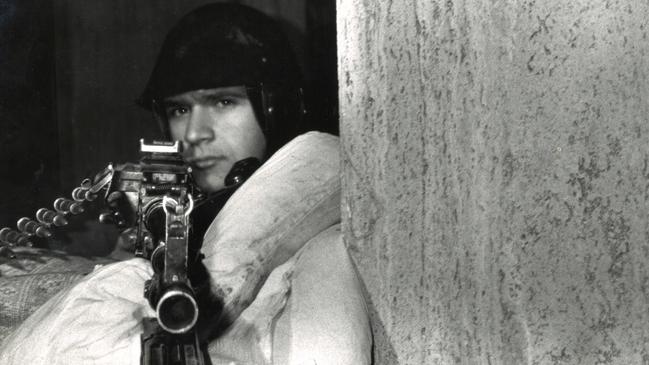

The scenes were deeply moving. I photographed and documented as much of it as possible. The photographs I took were leapt on by The Australian and published across a whole page in the weekend edition.

By December 30, the world’s interest in the violent overthrow of the cobbler’s apprentice-cum-dictator president was waning. The appetite of our editors for stories from the fall of another communist domino was temporarily satisfied.

I paid a local to drive us to the Bulgarian border. Nicolas was exhausted and unwell. It was time for me to step up and help. I dragged our bags over the bridge above the Danube before organising the next leg of our journey to Turkey, on to Istanbul and to the airport for my immediate return flight to London.

Arriving in the late afternoon of New Year’s Eve, there was time to return quickly to the flat in Clapham, shower, change, and go out to celebrate with friends to usher in the start of 1990.

But strangely, or so it seemed at the time, I found it difficult to turn off the fresh experiences of Romania. It was hard to join in a night of cheerful partying at the Café Royal on Regent Street.

For years afterwards, I wondered why I had needed to quietly slip away from the party. Why I lay down under a big table in a darkened and empty upstairs conference room, away from the dancing and cheering, while I recalled images from the streets of Bucharest as my friends drank champagne and sang verses from the Scottish folk song Auld Lang Syne.

I didn’t understand back then that reporting on carnage, seeing death and destruction, trying to make sense of it, can take a toll. At 22, all I had wanted to do was race off to the next story.

The London posting overlapped with revolutions across Eastern Europe and conflict in the Middle East. It put me in Berlin as the wall came down in November 1989. In Jordan and on the Iraqi border during the first Gulf War.

In Spain and the island of Majorca on a successful chase for a runaway Australian businessman fleeing creditors, Christopher Skase. The Great Skase Chase, as the headlines declared.

In Scotland for British Open golf tournaments and long walks following professional golfers Greg Norman and Wayne Grady around the heather. At Wimbledon for the tennis. And in Paris for the French Open.

For the past 25 years, home has been Brisbane and for most of that time I’ve investigated and reported for The Australian.

I’ve grown up with this newspaper. As a boy I watched my parents carefully turn the broadsheet pages and devour every story. My Air Force pilot father’s fascination with the paper must have contributed on some level to my passion for it and for journalism.

The Australian has shaped our values. It has taught me to take calculated risks, always be curious, trust my instincts, obsess over the factual detail, and avoid groupthink. It has backed me to the hilt in every story and investigation.

In 2018, when my old Queensland flatmate Paul “Boris” Whittaker (now Sky News chief executive) was editor-in-chief of The Australian, the newspaper indulged my idea for a leap into the unknown – podcasting – to investigate and produce a series about the disappearance of a Sydney mother of two, Lyn Dawson.

A podcast series which would say her husband, Chris, had been allowed to get away with Lyn’s 1982 murder.

We called it The Teacher’s Pet. We took enormous legal, journalistic and financial risks to bring it out.

It culminated in 2022 in the Supreme Court in Sydney with Chris Dawson’s conviction, 40 years after he killed Lyn. There have been almost 100 million downloads of the original podcast and the related series called The Teacher’s Trial. It helped to achieve justice and became the most consumed story in News Corp’s history.

It would not have been possible without The Australian.

As it happened

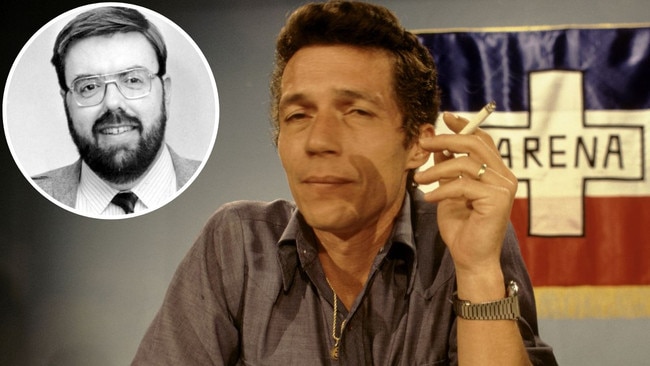

The Australian’s Nicolas Rothwell, in Bucharest with Hedley Thomas, filed on the death of a dictator for this story, published January 6-7, 1990

The long, brutal life of Nicolae Ceausescu, Romania’s dictator for the past 24 years, came to its appointed end early yesterday when he and his wife Elena were executed on charges of taking the lives of thousands of people.

So ends the reign of Eastern Europe’s most extreme, most sanguinary Stalinist tyrant – a leader who imposed medieval privations and sufferings on his subjects, all the while indulging himself in the lifestyle of the Roman emperors as whose latter-day heir he styled himself.

But behind the death of the tyrant remains a nation still convulsed by civil war and the stench of conflict, and a capital torn in two by the pressures of joy and grief.

The corridors of Romania’s Central Committee building – heart of darkness of the former regime – are still soaked with blood and strewn with shards of glass.

Tanks and armoured cars stand guard as vast crowds celebrate the downfall of Ceausescu, while the dreadful secrets of the dictator are coming to light at last.

As fighting began to abate in Bucharest yesterday, it became clear the resistance of Ceausescu’s elite Securitate secret police was being gradually wiped out by the Romanian army.

The people of the capital staged a mass rally before the Central Committee building.

Inside, amidst wreckage from the battles that have raged in the building throughout the past five days, Professor Dimitri Masilu, one of the leaders of the National Salvation Front, outlined his program for the country’s political future.

In the great avenues of Bucharest the mood is one of victory mingled with mourning. Altars have been raised to the victims of the revolution. Before them, people stand sobbing helplessly, holding photos of their dead children, and crossing themselves over and over.

60th Anniversary Witnesses to history

For a journalist, no story comes close to this one

The Australian’s former US correspondent was outside the Capitol on the day an angry mob invaded, urged on by Donald Trump.

Simple instructions: ‘Wear a ballistic helmet and a bulletproof vest’

The kibbutzim might have been tiny villages but they were the model, in miniature, for how a future Israel could have looked next to its Palestinian neighbours. By all rights, our reporter shouldn’t have made it there. But he did.

A large Indigenous man on my porch had an unexpected message

The story of a marriage forbidden revealed systemic racism and led to a life-long connection. For our 60th birthday, Hugh Lunn recalls this touching story.

Inside story: How Osama bin Laden hid in plain sight

The Australian’s then-South Asian correspondent had numerous run-ins with armed Pakistani police while covering the story of the decade. But nothing they could dish out could have been worse than having to tell the editor she’d been kicked out.

Cold, furious: The most evil man I have ever met

Getting to interview this man was challenging. He hated ‘gringo’ journalists and had vowed he’d never talk to one again. All of my peers warned me he goes crazy if you ask him about the death squads. But I had to try.

‘Stop the presses’: breaking the news of new pope

When the wisps of white smoke billowed from the Vatican chimney, The Australian newspaper had long been put to bed. Our correspondent couldn’t wait another day to file. We share this story for our 60th anniversary.

The first big yarn to take a toll on Hedley Thomas

Being sent to cover the bloody overthrow of the communist regime in Romania was a seminal experience for a young reporter who would become one of The Australian’s most highly acclaimed journalists.

At the scene of the story that gripped the world

Reporting from the muddy mouth of the cave complex as a monsoon loomed, it felt crushingly inevitable we would be relaying grim news about a trapped junior soccer team. But then came a sudden turn.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout