Simple instructions: ‘Wear a ballistic helmet and a bulletproof vest’

The kibbutzim might have been tiny villages but they were the model, in miniature, for how a future Israel could have looked next to its Palestinian neighbours. By all rights, our reporter shouldn’t have made it there. But he did.

So much of my time in Israel was spent thinking about the paradox of the southern villages – the kibbutzim, as they’re called. You might think that’s a peculiar point to dwell upon. What about the egregious security failures of October 7 or the plight of the hostages or the geopolitical radiation measurable in curies?

All worthy and important matters, none of them more so than the hostages. But it’s the liminal space along Israel’s southwestern borders that kept shouldering its way into my consciousness; the communities that flourished at a jogging distance from mortal danger, positioned at the demarcation line between a messy Jewish democracy and a genocidal Islamic autocracy under Hamas.

The mere existence of these villages under flight paths of rocket fire would be easier to explain if the residents were religious ideologues laying claim to a God-given right. Or if they were ultra-nationalists bent on thumbing their noses at the Palestinians. But they were neither.

They were farmers and peaceniks; liberal, secular, avowedly unpretentious in their sandals and loose-fitting clothes. Until October 7, they had cultivated friendships with their neighbours in Gaza, the 18,000-odd workers given permits to cross the border each day, some of whom took jobs on the kibbutzim and earned eight times the monthly Gazan salary of 1200 shekels.

But living with missile fire paled against the dread of infiltration. It’s why men slept with handguns beneath their pillows – a noble but feeble backstop, because when all was said and done, their pistols were no match for the Kalashnikovs and belt-fed machine guns brought in their hundreds across the border.

Why live under these conditions? We know it was trying for some. Shiri and Yarden Bibas, kidnapped from Nir Oz with their red-headed children, one-year-old Kfir and four-year-old Ariel – arguably the most renowned hostages in Israel – were fed up with the rockets. Their plan was to drive north on the morning of October 7 and search for a home near the Jordanian border, the Hashemite Kingdom having kept its peace with Israel since 1994.

Then you meet a guy like Maor Moravia, a married father and lifelong devotee of Kfar Aza, a kibbutz huddled three kilometres from Gaza in a region known as the “Envelope” because of its proximity to the shelling. Moravia and his family survived October 7 by hiding for 20 hours in a safe room until the army arrived: “As long as Hamas is able to do this again it’s very hard to see myself going back there.”

We meet in a garden of the Shefayim Hotel, near the coastal city of Netanya, where shell-shocked survivors were transplanted in the hours after the massacre. Soldiers gave Moravia and his family five minutes to grab everything they could (he chides himself for taking house keys, saying: “Keys for what? I can’t open anything with it”) before rushing them under fire to an extraction point.

It seems only fitting, days afterward, when a ministry official informs me I’ve been granted entry to Kfar Aza, to get a message to Moravia and ask if he’d like anything brought back. By this time a neighbour has already returned to the village and retrieved essential items for him. His wife has a request, however, if we’re going to Kfar Aza. She’d really like a flower from their garden, if that’s possible.

The Shuva Crossing is a staging point just outside Kfar Aza, and at this range it would take five seconds for an unguided Hamas rocket to fly on its demented path and come crashing at my feet. Plenty of the missiles don’t even make it this far; they loop around and explode back in Gaza. About one in four, by the Israel Defence Forces’ estimate.

There’s no Iron Dome defence system here, which is why a soldier points to a ditch alongside the roadway if we suddenly need to lie prone. The even smarter money, he says, is to run into the fields. “Just stay away from cars,” he warns. “They become shrapnel.”

Access to this closed military zone required daily prodding of embassy and military officials, or advisers in the Netanyahu administration. Something like 2500 foreign journalists arrived in Israel after October 7 and the unambiguous priority had been to favour those from American and British outlets. It’s all part of the parallel war being waged for hearts, with Benjamin Netanyahu’s first foreign interviews granted to Fox News and CNN. “If you worked for the Washington Post you’d get whatever you want,” says a senior Netanyahu administration official.

So by all rights, I shouldn’t have made it inside Kfar Aza for months. I can only assume my edge on the press pack came from nudging one particularly high-ranking IDF official whose number I cadged along the journey, the pestering of whom probably led to the WhatsApp message received on the morning of October 18, eight days after my arrival in Israel. The instructions were simple: “Shuva Crossing. 1300. Wear a ballistic helmet and a bulletproof vest.”

To arrive in Kfar Aza is to be greeted by eucalyptus trees swaying in the breeze, planted decades ago to drain the marshes that once stifled the desert agriculture. It’s early afternoon, and the heat is like a kiln. Beyond the security gate are Kandinsky bursts of colour from the sculptures and murals adorning the bus stops. Children’s bicycles, mounted for decoration, pop with splashes of green and yellow. It’s hardly the scene of carnage I expected.

But a stray bullet casing is enough to pierce the reverie, then the sight of a tattered ballistic vest drying in the sun. There’s broken glass crunching underfoot, and soon a Jeep Cherokee spattered with holes so large even the untrained eye would know they weren’t caused by a handgun.

But it’s never the shot-up car or the stench of bodies or the carcass of an exploded truck that pinches the soul like the found relics from before – the welcome mat, the sassy fridge magnet, the fragrant lemon tree in full bloom. No such totems, of course, in the houses vaporised by what the IDF says was thermobaric weapons. Israeli archeologists sifted on hand and knee to help with victim identification here, searching for a stray tooth or a fragment of bone in the ash heaps.

Three months will pass before I cross into the Gazan city of Khan Younis, and it’s by chance that I find a soldier named “Tsori”, from Kfar Aza, who sheltered in a basement on October 7 with his wife and two children, a toddler and a newborn.

“God saved him,” says a fellow trooper, acting as our translator, and he confirms that hunting down militants is freighted with an extra layer of significance for Tsori. “It’s his mission in life to be here.”

We’re trudging back to the Jeeps when another soldier bursts forth to say something. “I’d like to just put it on record,” he says of Tsori, “that he’s fearless and has killed more terrorists than all of us.”

And this is it, right? Killing bad guys is supposed to lay the pathway for Israelis to return to the southern districts and revive their beloved kibbutzim. Already a tentative trickle has started in Sderot, an Israeli city inside the envelope attacked on October 7, and the same will eventually happen in a rebuilt Kfar Aza, too.

And still, that nagging question of living under threat. It can’t just be down to the cheaper housing or the distance from noise and traffic. If an answer exists at all, it has to be in the fragile dream of statehood that Israelis have been gripping to since 1948. The kibbutzim might have been tiny villages but they were the model, in miniature, for how a future Israel could have looked next to its Palestinian neighbours; their relationships unclouded by politics, both sides made passive in cooperation, in greater wealth, in higher living standards, the binding agents for a better life.

As it happened

Yoni Bashan’s report from the devastated kibbutz, Kfar Aza, was published October 20, 2023

It’s been two weeks since Hamas terrorists rampaged through southern Israel on a campaign of mass slaughter of civilians. Two weeks, yet inside the village of Kfar Aza, the nauseating smell of incinerated tyres, of singed clothing and melted plastic, of smouldering wreckage still hits you like a blaze when the wind decides to stir.

Two weeks, but it could be an hour. Untouched houses are preserved in time, school bags and shoes left by the door as though everyone’s just stepped out for a minute. Like it’s still early on Saturday, October 7, and gunmen haven’t crept into the village yet … But turn a corner and reality rises with the breeze to puncture the senses, a stench of decay, of dead dogs, of food left rotting in abandoned refrigerators.

Gone are the corpses but everything else is here; the terrorists’ pathway traceable from a busted security gate to cars shot up with Kalashnikov rifles, to crumpled paragliders that flew them in, and homes scorched using thermobaric weapons.

Not the entire home; mostly just the concrete safe rooms where residents sheltered. To witness these charred, broken husks … is to understand the terrorists always planned for maximum civilian carnage – that this was never going to be an engagement between territorial armies. Whether it was Kfar Aza or Nirim or Nahal Oz or Be’eri, civilians were always the bounty.

These were attacks that arrived in waves, ending with hostages captured and Gaza residents flooding in to loot homes with impunity. It’s why women’s clothing was left strewn in the middle of the streets in Kfar Aza, and why electrical appliances and furniture are missing. Vehicles are gone, of course. Even cows were taken across the border.

Reclaiming the village involved a painstaking military operation. Hence the letter “C” sprayed on doorways to confirm the building was “cleared”. They were still being secured one week after the attacks.

60th Anniversary Witnesses to history

For a journalist, no story comes close to this one

The Australian’s former US correspondent was outside the Capitol on the day an angry mob invaded, urged on by Donald Trump.

Simple instructions: ‘Wear a ballistic helmet and a bulletproof vest’

The kibbutzim might have been tiny villages but they were the model, in miniature, for how a future Israel could have looked next to its Palestinian neighbours. By all rights, our reporter shouldn’t have made it there. But he did.

A large Indigenous man on my porch had an unexpected message

The story of a marriage forbidden revealed systemic racism and led to a life-long connection. For our 60th birthday, Hugh Lunn recalls this touching story.

Inside story: How Osama bin Laden hid in plain sight

The Australian’s then-South Asian correspondent had numerous run-ins with armed Pakistani police while covering the story of the decade. But nothing they could dish out could have been worse than having to tell the editor she’d been kicked out.

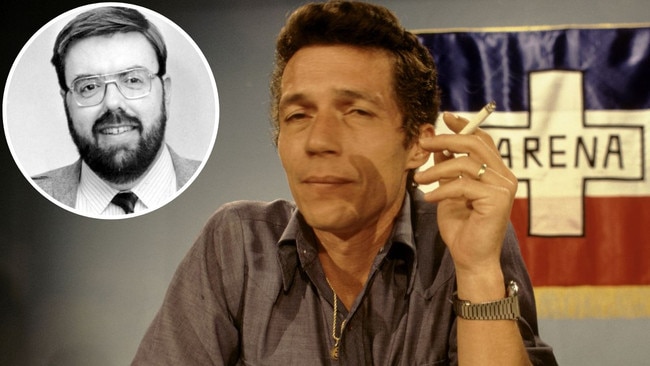

Cold, furious: The most evil man I have ever met

Getting to interview this man was challenging. He hated ‘gringo’ journalists and had vowed he’d never talk to one again. All of my peers warned me he goes crazy if you ask him about the death squads. But I had to try.

‘Stop the presses’: breaking the news of new pope

When the wisps of white smoke billowed from the Vatican chimney, The Australian newspaper had long been put to bed. Our correspondent couldn’t wait another day to file. We share this story for our 60th anniversary.

The first big yarn to take a toll on Hedley Thomas

Being sent to cover the bloody overthrow of the communist regime in Romania was a seminal experience for a young reporter who would become one of The Australian’s most highly acclaimed journalists.

At the scene of the story that gripped the world

Reporting from the muddy mouth of the cave complex as a monsoon loomed, it felt crushingly inevitable we would be relaying grim news about a trapped junior soccer team. But then came a sudden turn.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout