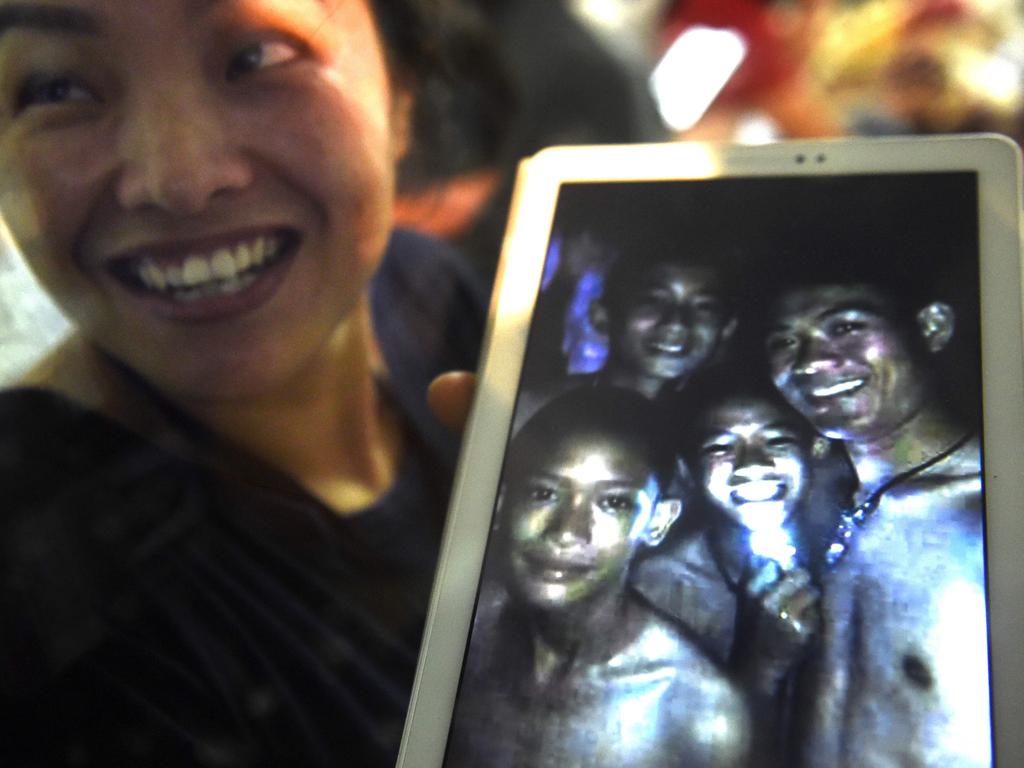

At the scene of the story that gripped the world

Reporting from the muddy mouth of the cave complex as a monsoon loomed, it felt crushingly inevitable we would be relaying grim news about a trapped junior soccer team. But then came a sudden turn.

I was ankle deep in mud and battling never-ending deadlines as rain poured through the tarpaulin onto my head and nearby power cables installed for a media pack that had vastly outgrown its makeshift home. I grabbed a poncho, threw it over me and my laptop, and kept writing.

Had a downpour ever been less welcome? The deluge that day sent muddy rivulets streaming down the hillside and into the mouth of a cave where an army of people was racing to pull off what would become one of the most celebrated rescues in modern history.

There had been six days of unprecedented international effort since 12 young Thai footballers and their 25-year-old coach were found alive in northern Thailand’s Tham Luang cave complex, and suddenly the rescue appeared to stall.

I had arrived hours after their miraculous discovery on a muddy rise inside the flooded cave on Monday, July 2, in 2018, but awoke the following Saturday before dawn to torrential rain on the roof of my $9 a night hotel room. My heart dropped.

The night before, a Thai military commander had told a huge global media pack gathered outside the cave he was praying for three more days of respite – just three – from a looming monsoon that could reverse a week of Herculean endeavour.

A maze of guide ropes and pulleys had been engineered inside the cave to aid a rescue bid everyone thought would start on Saturday. Dozens of oxygen tanks were in place along a 3.2km route – half of it completely submerged and pitch black – in preparation for a rescue plan that, at first, had sounded so preposterous that even Elon Musk’s “kiddy submarine” had, for a brief moment, made more sense.

Then a former Thai Navy SEAL, Saman Gunan, drowned in the cave on Friday after losing his mouthpiece in the most treacherous section, a narrow, flooded S-bend tunnel just 37cm high.

Now it seemed the weather gods had spurned the prayers of an entire country, and millions more across the globe who had spent the week monitoring phones, computers, televisions, newspapers and radios for updates. Would rain sink this incredible rescue? Had authorities lost their nerve after Gunan’s death?

In reality, the operation paused just long enough to allow Australian anaesthetist and cave diver Richard Harris to fly in with long-time dive partner Craig Challen and assess whether the boys could be put to sleep for the rescue.

The answer was yes.

All 13 would be zonked out on ketamine for the potentially deadly extraction, despite the denials of the then Thai prime minister Prayuth Chan-ocha – one of numerous red herrings fed to media that week.

“If we don’t start now we might lose the chance,” Chiang Rai governor Narongsak Osottanakorn, the face of the operation, admitted that night.

By Sunday morning it was on, and the marathon turned into a sprint. From start to finish the Thai cave rescue was that rarest of media events; a positive news story in a year of disasters, and the world could not get enough of it. Everyone seemed to want to talk about it. Strangers reached out on Twitter and Facebook from across the globe and around the clock. All asked the same question: can it succeed?

I wrote thousands of words that week, one of the most intense of my career, but until rescuers pulled all 13 out alive three days later I would not have dared to guess. Privately – if a sentiment shared among hundreds of journalists can be considered private – I thought if even half of them survived it would be a triumph of sorts.

Yet against those odds it felt like the world was pulling together in the most primal of common goals – the protection of children. Even Donald Trump was tweeting words of encouragement. It was impossible not to get swept up in it all.

If the first of many miracles was that the boys were found, the second was the Thai junta allowing foreign military and civilian specialists with greater experience to take the lead.

Updates from Governor Narongsak came daily – if often very late – but they were never enough to satisfy the global appetite for a story that had everything: pathos, suspense, heroes, even mysticism.

I had spent the week raking that corner of the Golden Triangle for insights into how these wiry provincial boys had survived 10 days without food or water, and how a united nations team of civilian and military rescuers planned to extract them.

The Wild Boars had spent their week recovering inside the cave, eating power gels while begging for pad kra pao, and being taught how to dive.

Above, hundreds of volunteers searched for a safer alternative; another entrance or “chimney” through which the boys could be hauled up. None was found. Others plugged holes in the cave roof and dammed rivers to stop the water from rising. A billion litres was pumped from the cave, creating life-saving air pockets.

Like everyone there I was powering on three-in-one coffees and bowls of noodles served by locals who had raced to the site with gas rings to fortify desperate families camped there since June 23, when their boys had not returned from soccer practice. Soon the Thai imperial kitchen would take over as the rescue force expanded.

An operation that began with a team of Thai Navy Seals had grown to almost 10,000, turning a remote tourist site into something more like a 24-hour movie set thrumming with cameras, lights, muddy extras in gumboots and cautious optimism.

The race against the weather only heightened the frenzy for information, but the story’s heroes – cavers with a penchant for dark, solitary places – were not easy celebrities. Dozens of tarpaulins were strung up to accommodate workers, media and food providers, but the cave mouth in front of us was screened off, frustratingly – if understandably – out of bounds to media, as rescuers moved in and out.

Ranger huts and offices were repurposed as rescue headquarters hosting convoys of Thai VIPs, who regularly came speeding in for meetings with counterparts from 16 other nations.

A hundred specialist cave divers flew in from across the world, all eager to play a part.

There were even attempts to lay phone cable to where the boys were being prepared for what lay ahead, and – although no one said so – for 13 families at the edge of their mental and emotional limits to speak to their children for perhaps the last time. When that failed, the divers ferried notes between the boys and their parents.

“I am waiting for you in front of the cave,” one mother wrote to her son. “I want to hug you and I want you to not give up. I want you to believe that you can do it. I love you more than anything else.”

I cried over those letters – I still do – wondering if this rare story of hope would end with me mining fresh grief for a front-page story.

Then, on Sunday, another miracle. All media had that morning been moved to a new media camp in a carpark in Mae Sai, 10km from the cave.

We sat there all day, working phones, swapping theories, yelling information across desks, searching for a sign that finally came late in the afternoon with the sudden cacophony of helicopters and ambulance sirens.

One after another, agonising hours apart, authorities confirmed the first four boys had been successfully dived out of the cave. Alive!

Only as that first confirmation came through did I realise how invested I had become in a happy ending. Although it felt too early to cheer, as others did, my own rising excitement leapt out from The Australian’s live blog and news pages with every fresh rescue over those three days.

It took 11 hours to extract the first four boys then nine hours on Monday as rescuers fine-tuned the operation. The last five came out on Tuesday and, when they did, I felt overwhelming elation and relief.

A day later, The Australian, The Guardian and The Sydney Morning Herald broke in unison the story of how the pumps failed as rescuers packed up inside the cave, forcing dozens to run for their lives from a wave of water.

For many Thais, it underscored the mystical forces behind the boys’ survival; just as those same forces would also explain tragedies still to unfold.

Wild Boars captain Duangphet “Dom” Promthep, who turned 13 inside the cave, committed suicide in February 2023 in a British boarding school known for turning out professional footballers – five months after leaving Thailand in a blaze of publicity.

The pressure of unwanted fame had driven him to the other side of the world where loneliness and despair had taken hold, his mother told me in Mae Sai, three months later.

Her inconsolable grief would ultimately make the front page.

As it happened

For 17 days, the world was gripped by the story of the boys in the cave. The Australian’s Amanda Hodge was one of the first to report on their rescue, published July 11, 2018

A crack team of international cave divers last night completed one of the most extraordinary underground rescue missions ever attempted, pulling the last of 12 young Thai footballers and their coach to safety from deep inside a flooded cave complex in northern Thailand. Shortly before 10pm, Thai Navy SEALs confirmed the final four boys and their 25-year-old coach from the Wild Boars soccer team had been freed from Tham Luang cave after 17 days trapped in pitch darkness on a small sandy slope just above the waterline, 3.2km inside the winding cavern.

“Thai navy SEALs confirm ALL 12 boys and coach now out of cave. An incredible, an extraordinary rescue mission,” the SEALs said in a tweet. “Congratulations to the hundreds of people involved in this effort. Now for the three navy SEALs and one medic. Hooyah.

“12 wild pigs and coaches out of the cave. Safe everyone. This time, waiting to pick up 4 Frogs. We are not sure if this is a miracle, a science, or what.”

Late last night the three SEALs and a medic were reported to be on their way out of the cave also. Relatives of the boys waiting outside the cave thanked rescuers.

But at the house where coach Ekkapol “Ake” Chantawong lives with his grandmother, the news of the rescue had not yet filtered through. A call from The Australian was the first his family knew of his rescue.

“I am so happy,” Ake’s aunt Umporn Sriwichai said as cheers could be heard in the background. “I want to jump in the air. I have been waiting and watching the news and when he arrives at the hospital I will go.”

Songpol Kanthawong, one of only two members of the Wild Boars team who did not go to the Tham Luang caves on June 23, told The Australian he was watching television when he heard the news and was “glad” his friends were all safe.

More Coverage

60th Anniversary Witnesses to history

For a journalist, no story comes close to this one

Simple instructions: ‘Wear a ballistic helmet and a bulletproof vest’

A large Indigenous man on my porch had an unexpected message

Inside story: How Osama bin Laden hid in plain sight

Cold, furious: The most evil man I have ever met

‘Stop the presses’: breaking the news of new pope

The first big yarn to take a toll on Hedley Thomas

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout