Cheng Lei: What 1184 days’ jail has taught me about liberty

The Australian journalist who was detained for more than three years in China reflects on the true value of freedom.

When you are locked up, you become obsessed with freedom.

I thought about freedom for 1184 days. Because freedom is like health – losing it is more acutely felt than having it.

Freedom of the mind can unchain the psyche.

When you have nothing except freedom of thought, it rewires and kick-starts the brain. I wanted to be the person who could think herself in the ocean, while in a cell.

When the doors were locked, my mind roamed to infinity.

Books took me to crazy fights in Costa Rica, to climb Everest with George Mallory, to find nourishment in friendship in Guernsey during resistance, to be mesmerised by a willy-willy in the outback.

Imagination gave me the key to make each day different, to create fun.

Officers used to upbraid me for laughing. They’d open the door and look me up and down: “What are you so happy about?”

It felt like they were imprisoned, so bound by indoctrination they couldn’t squeeze joy from life.

* * *

In Chinese, the words for “freedom” are zi you, which literally means “self as you are”. But as I ruminated in the grey reality of the cell, I had not been “self as I am” even before August 13, 2020 – the day I was locked up.

Like many others who work and live in China, or even those who deal with China, I had already surrendered many freedoms.

We gave up the freedom to criticise the government or its leaders. (In detention, the No 1 rule was not against fighting or even weapon-making, it was against vilifying the government and its leaders.)

We gave up the freedom to protest because we all held vested interests – our jobs, our assets, our trade.

We accepted that the locals had even less freedom. That human rights lawyers were locked up and their families intimidated by the secret police. That there was heavy media censorship about what to report, what not to report, and how to report.

That in Chinese art and literature, the noose of state control got tighter every year.

* * *

‘The best way to keep a prisoner from escaping is to make sure he never knows he’s in prison.’

– Dostoevsky

China is a locked paradise. It is safe and efficient and increasingly prosperous; the light shows on the cities’ main buildings are magnificent; massive sporting games are run faultlessly; everybody seems to be going somewhere, doing something; the news is always upbeat.

If you are a visitor, you can have a great time biking around the alleys, trying the food, talking to locals, taking the high-speed train, cooing at the pandas, gawking at old geezers doing tai-chi in the park and old ladies dancing en masse in red pantaloons.

If you are a young local, you’ve grown up with nothing else but the rhetoric that your nation is finally getting its act together and the international establishment doesn’t like it. You want to stand up to Western nations’ bullying and show that your version of freedom is better.

If you are a trading partner, you feel very fortunate. The country buys so much and pays on time; its politics are stable (frighteningly so).

The more you’re seduced by what you see, the more willingly you surrender your freedom.

You start to make excuses for the regime, seeing the liberties as expendable for the sake of better, say, pandemic control. You doubt the ability of China’s billion-plus citizens to handle freedom; better let the central government decide.

You forget that you are on a massive movie set, seeing a facade of freedom where everyone dons invisible straitjackets and velvet handcuffs.

Live there a bit longer and you find you cannot use the apps you are used to. Talk to locals about how they feel about the government and their anger and find they are scared, disillusioned, or they disappear.

Try to protest or petition and you would be roughed up. Try to access certain content online or use any of a growing lexicon of sensitive words and your social media is blocked.

Ask artists and writers and performers about their creative process and you are shocked by the restrictions. Seek out civil rights lawyers and chances are they’re in jail – and you are not allowed to visit.

Ask journalists how much freedom they have in reporting and they may laugh and weep at the same time.

Ask the families of Chinese journalists who report for international organisations and you find they are often harassed by the secret police.

Do all of the above and you will already have been visited by my friends from the Ministry of State Security.

And if you are lucky enough to become a long-term guest of the MSS’s free accommodation, you will experience first-hand how worthless individual freedoms are against the state machinery.

On the 35th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre, my son asked me what the June 4th incident was all about. I explained how in 1989 Chinese people went through the most unafraid seven weeks in recent history. How the crackdown that followed instilled fear and disillusionment.

And how the regime vowed never to let civil liberties get close to that again.

Now you cannot go to Tiananmen Square without ID checks, without being scrutinised on massive banks of screens, without rubbing shoulders with plainclothes police.

The regime wants the have-nots to become the have-somethings so they’ll have something to lose by rebelling.

China has conducted the most successful mass brainwashing experiment to date: somehow, cutting back on personal freedom has been recognised as good governance.

* * *

When I regained my physical freedom, I felt reborn. I saw and heard and smelled and tasted again.

Life was even bigger and brighter than I had imagined.

More interesting was the journey of mental liberation. I still had vestiges of the restraints in the subconscious. In the middle of sleep, after leaving an arm out of the covers, I would fret for a moment that I had broken the rules.

When I laughed too loudly, I mentally checked myself before realising I was not in that place anymore.

On so many levels, I could not help the comparison – Australia: freedom, China: not.

I saw how accessible politicians were (even China took advantage of it, to wit the meeting of Paul Keating and Wang Yi).

Look at how easy it is to get into government buildings. How easy it is to find out information.

How easy it is to have your views heard.

How easy it is to show your discontent.

How easy it is for the media to tell the truth.

The media in China spread lies about me – that my parents were uneducated, pressured me financially and that’s why I sold out China for money from Australia and America until a slip of the tongue on-air exposed my long-term embedded spy status.

The smear campaign even came to Australia when the Chinese media here translated the made-up stories.

Because dictators often start out as freedom fighters, they are far more suspicious of free thought and speech and gatherings – it is how they got into power.

Under China’s freedom, the media and cultural arts are controlled for the “stability” of the country, criticism is disallowed for the “security” of the nation, protests are banned for the “harmony” of the society, religion is allowed only under the auspices of the CCP. How many truly believe giving up those freedoms is worth it? How many pretend to drink the Kool-aid and save up for immigration?

Western democracies are in a conundrum.

Disengage and the locked paradise withdraws further, tightens alliances with similar countries, uses propaganda to widen the “us against them” rift.

Engage and there is the battle of ideology, which China seems more unwilling to concede on.

How to deal with China when it’s unapologetic about curtailing civil liberties?

* * *

Initially in incarceration, I could not move without the permission of two guards who were constantly by me. When I was transferred to detention, I could get up and walk in the cell! That felt liberating.

Even though I was physically restricted at all times, the small mercy was that I had freedom to think.

Not so in my parents’ generation, who had to recite political mantras publicly every day, who kept no diaries because the Red Guards could use them as evidence of counter-revolutionary thought.

For years after they arrived in Australia, Mum and Dad revelled in being able to bag China without looking over their shoulders.

When Russian opposition figure Alexei Navalny died, I grappled with the question: which regime is less free, one in which an opposition voice is quashed and people openly grieve or not being able to see opposition at all?

Freedom needs a counterpoint. Richard Branson once spent a night in jail for dodging taxes, after which he said “everyone should spend at least a night in jail”, meaning otherwise you’re not aware of the treasure that is freedom.

So 1184 nights may be overdoing it, but nowhere did I cherish freedom more than in incarceration. Nowhere did I realise more clearly how we squander freedom.

All of my cell mates regretted not having travelled more, shown more love to their loved ones, done things they’d dreamt of doing.

Nobody thought they should have bought a bigger house or made more money.

Now, the moment I am in stasis, I ask myself – am I doing justice to my hard-won freedom? Am I living the way I would if I knew I wouldn’t be free one day?

Am I learning all I can in case one day I lose access to knowledge?

Am I moving closer to my dreams in case one day there is no horizon to dream against?

Paradoxically, when you have nothing, you are free. As soon as you have something to lose, you lose courage to change.

It’s also true that as soon as you love someone, you cannot just walk away, up and change.

But these can be the shackles that give our lives meaning. As Charles Bukowski asks, “When nobody wakes you up in the morning, and when nobody waits for you at night, and when you can do whatever you want, what do you call it, freedom or loneliness?”

* * *

The contrast in freedom was never clearer than when Chinese Premier Li Qiang visited Australia in mid-June, when I was accorded much more importance than warranted by Chinese diplomats – blocking me from the cameras or blocking me from covering a meeting. In full view of other journalists. Flouting protocol.

To Western countries, this was unthinkable, unbelievable and unacceptable.

To the Chinese it is par for the course. From Mao’s “Politicians run the newspapers” to Xi’s “The media’s name is the CCP” – what are journalists but political puppets?

The brazenness of the diplomats’ behaviour says volumes about how international criticism is secondary to domestic optics. Perhaps the worry was: if an ex-con spy can cover leaders’ meetings, what does that say about her crime and the system that convicted her?

What ensued was an international media flurry compared with total blackout in China – the Chinese internet is a prison against truth.

Even when Chinese people move out of China, the fear remains.

Recently I was in Canberra to moderate a discussion where the interpreter quit from fear of interpreting my panel guest’s comments which were likely to be anti-CCP.

The common perception is that the slightest association with someone seen as anti-China is dangerous and harmful.

As far as authoritarian states go, China is the most tricky.

It is more subtle than Russia, far more appealing and successful than Iran, North Korea or Cuba.

It is difficult to see China in its totality. There are aspects of its control that seem attractive.

Order. Efficiency. As China loves to brag, “We can do big things together”.

As long as small pockets of dissent are quashed; made examples of.

As long as the masses don’t experience real freedom and have no alternative.

We must help people shake off the insidious fear by speaking up in defence of personal freedom, within Australia and outside its borders.

If we let the fear eat our words as well, one day we’ll be so comfortable in our self-censored virtual cells we won’t even feel it; we’ll forget what freedom feels like.

If freedom is our statement about humanity, what are we saying?

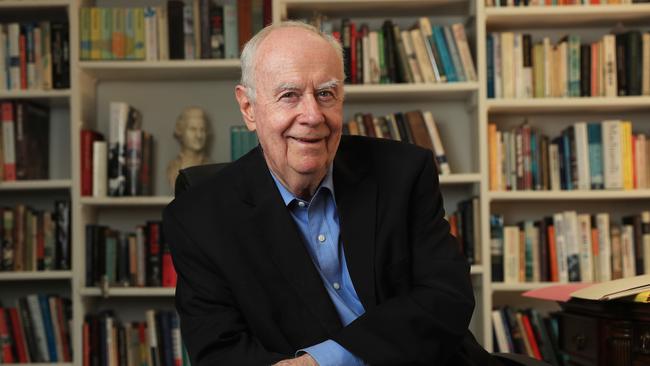

Cheng Lei is a China-born Australian TV journalist who worked in China and Singapore for 18 years for CNBC and China’s state TV English channel. She spent three years and two months in prison in China on trumped-up espionage charges. She works as a presenter for Sky News Australia

Big Ideas

The stories Trent Dalton is most proud of

For 23 years, as a working journalist, I have been documenting Australians who simply refuse to succumb to whatever pervading darkness threatens to blacken their light. These stories are the keepers.

The trendy disparagement of science is un-Australian

Richard Scolyer and Georgina Long faced the worst possible scenario when Richard was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer. The melanoma researchers fell back on their medical knowledge to make a brave decision.

The turning point for all strong women? It’s not motherhood

It’s the pain and confusion that is my strongest memory of the worst year in the lives of all women, I’m sure. It was my first insight into the complexity and competition of womanhood.

The balance is broken: What now for democracy?

Radical shifts in social order; technologies that shape as foe rather than friend; erosion of faith; an end to truth and facts. The strength of our good society is about to be put to the test.

‘No one is disadvantaged just because they are Indigenous’

No meaningful change comes from selling ourselves short through guilt politics. It comes from understanding our history in its entirety.

Ideas are the source of all power in human affairs

Political power may grow out of the barrel of a gun but it is an idea that compels someone to pull the trigger, to raise an army, to start a war.

There is no choice: a Holocaust survivor’s view of courage

A difficult choice is speaking out against the populist but morally reprehensible behaviour of the crowd. If the tipping point between democracy and anarchy is to be avoided, we, you and I, need the courage to fight for our democracy.

What 1184 days’ jail has taught me about liberty

The Australian journalist who was detained for more than three years in China reflects on the true value of freedom.

60 most influential people of the past six decades

To celebrate The Australian’s 60th anniversary, this masthead has brought together a list of those who have had an impact on all our lives.

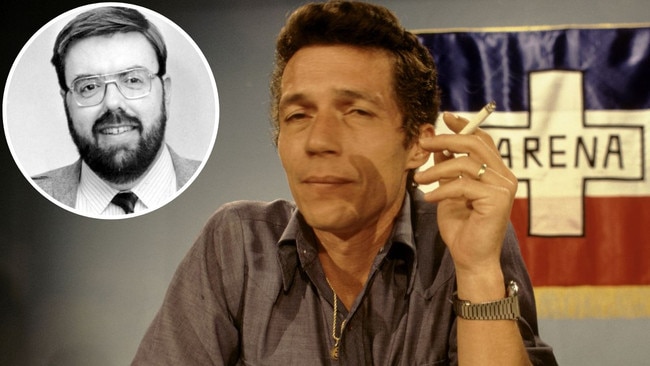

Cold, furious: The most evil man I have ever met

Getting to interview this man was challenging. He hated ‘gringo’ journalists and had vowed he’d never talk to one again. All of my peers warned me he goes crazy if you ask him about the death squads. But I had to try.

Loss is the best teacher.