The turning point for all strong women? It’s not motherhood

While this is obviously a lot of pressure to place on a 13-year-old and an approach not recommended in today’s parenting handbooks, I remember my heart expanding with pride. My parents thought I could do anything. In their minds, gender would not limit the fulfilment of my potential beyond the structural inequalities my young mind was yet to fathom. If Princess Leia could lead a rebellion, so could I.

I am not an academic, an activist or an expert on feminism, womanhood and identity. There are indicators of social and economic health that remind us how far women have come, and how very far we have to go. For some women – First Nations women, for example – the playing field is completely different and much harder. But I am a woman who has some experience of life and I have some words, so I can speak of my own story.

It’s easy to reduce my experience of womanhood to marriage, mothering and the usual anecdotes: I haven’t slept properly for 17 years; I do too much laundry and often not enough; my husband and I have a spreadsheet on the fridge with equitable roles for family members; sometimes those roles don’t feel so equitable to one or both of us and we argue.

These are important data points. There is humour, anger, respect and love in the quotidian moments of a marriage. There is all this and more in motherhood. But marriage and motherhood are not the places where I learned to be a feminist or where I developed my identity as a woman. Feminism, womanhood and I started long ago, the journey is ongoing and the lessons from the past help me navigate the future.

As a child, my identity was attached to my quirks, my achievements and my family, rather than my gender. I had a preternaturally large vocabulary and spoke like an Enid Blyton book. I could not hit or catch balls but, in my mind, I was highly skilled with a lightsaber. I spent a lot of time in my mind. I rarely went anywhere without a posse of cousins. To this day, Sri Lankan Tamils can remember my lineage but not necessarily my first name.

As a teenager, the achievements and quirks of all girls became subsumed in the harsh and sometimes brutalising assessments of our bodies, faces, hair, clothes, crushes and what we did on the weekend when our parents weren’t looking. The inadequacies of our bodies were overwhelming, and the strength of our characters became obsolete. Friends were suddenly more alluring than family. Although friends could be cruel, family was embarrassing and that was worse.

Our identities as women were forged in the crucible of high school, and in particular, the shitshow that is Year 9. I’ve had one daughter and three sons walk through its fires, and while my research has yielded inconclusive results about the worst year for boys, the worst year for girls is unequivocally Year 9. Every generation of woman in Australia I’ve spoken to concurs.

Something happened in Year 9 – sex, drugs and an amping up of the survival/killer instinct. I remember sitting in class on a Monday morning while the girls around me described in detail their weekend activities. I was riveted, nauseated and anatomically confused. My knowledge of the human body was extensive because my parents are doctors, and their idea of small talk is to explain how the systems of the body work.

But they are also Sri Lankan Tamil, and their lessons had completely bypassed the reproductive system for more than a decade. In an era before Google, I had my best friend, whose growing sexual knowledge was only surpassed by her knowledge of Middle Earth, something we stopped talking about in Year 9.

It’s that pain and confusion that is my strongest memory of Year 9. It was my first insight into the complexity and competition of womanhood. My closest friends and I had less and less to talk about. Moving from girlhood to the early stages of womanhood meant strained friendships, the prospect of breaking up with girls I’d known since childhood, and the uncertainty of who I’d have left.

It also meant that girls who were once nice or neutral became vicious. To this day, I remember the things they said to me 35 years ago in high school, but I cannot remember what we had for dinner last week. I also remember how other girls taught me to duck and weave out of the way (resistance was futile). The predator was fast, but the prey wasn’t stupid.

In my high school years, while my friends were going out, I felt locked up. While they were in undisclosed locations on a Saturday night, I was at home watching a marathon of 21 Jump Street and LA Law with my family. When there was/is kissing on television, we were/are all told to avert our eyes (well into our 40s). Womanhood during my high school years was represented by the physicality of Alien’s Ripley, the intellectualism of the X-Files’ Scully and the sexual confidence of Madonna.

As a teenager, I wanted contradictory things: I loved the safety of a conservative Tamil household and had no desire to leave it, but I wanted the freedom to leave it. I wanted to be able to choose. I wanted to be included in my friends’ weekend plans because I loved them, but I didn’t want to go. I was jealous of their experiences but, when I looked up new words in the Encyclopedia Britannica, I was horrified by them.

In our community, notions of virtue, chastity and cleanliness applied to girls but not to boys. As girls, we were assessed on the modesty of our clothing and behaviour. We were subjected to a suffocating level of community scrutiny that boys escaped. A woman’s reputation was “no less brittle than it is beautiful” (we all over-identified with Jane Austen, not as a clever critique of past social mores but a representation of our present ones). Agency in life, the universe and marriage could not be taken for granted. This gendered approach exists in many cultures across many eras, it wasn’t peculiar to ours. It was controlling and claustrophobic for girls of my generation. We wanted to explore the expanding horizons of adulthood but found Tamil womanhood was getting in the way.

It was also loving and liberating. I have always felt part of something larger than myself; something collective and empowering. As a teenager, I remember my parents, family and community making me feel safe and confident to do anything, to be anything. The fact I was not allowed to go anywhere was mitigated by the television, the public library, a Video Ezy membership, and an active imagination. Also, the many cousins.

My generation was the first to be raised in the refuge of Australia. My family was the migrant paradox – keen to contribute to their new home, to fit in (and remain unnoticed) but also afraid that we would completely assimilate. They often clung to cultural practices – including the gendered ones – that even in Sri Lanka have changed or been discarded. We existed in a cultural time capsule. As a parent, I have adapted to ignore the cultural constraints placed on girls.

Some of my adaptations are not especially profound. For example, my daughter is attired in clothing, piercings and a tattoo that in “my day” would have triggered a nationwide Aunty Alarm, calling for immediate intervention by any Tamil, related or otherwise. When I look at my child, I am instead relieved, because I know her well enough to know she respects her body and is comfortable with how she looks. I am inspired by her self-expression.

Some of my adaptations are profoundly personal.

For example, my daughter is encouraged to go to temple on any day of the month, except on the day a new Star Wars movie comes out. Women bleed therefore we can conceive. If old Hindu men want more Hindu babies then this singularly female ability should be deified, not used to degrade us.

Some of my adaptations are more subtle because the battleground is, too. In the home, Tamil women (regardless of their careers) are the presumed primary carer, like women of many cultural backgrounds. We are the Special Forces of domestic work, highly sensitised and alert, trained to react immediately to every call for food, homework support and clean underwear. However, in assuming this role, women are sequestered from valuable interactions. When we are at the stove, the laundry or Kumon, we are far away from the debates, the banter, the arguments, the jokes and the conversations that deepen our relationships and sharpen our minds. We are drained of opportunity to pursue other passions, activities, our careers or even “just” to rest. As many women know, this is no small thing.

My husband, who undoubtedly married me for my mind, my skill with a lightsaber and my sense of humour, did not enter our marriage with Tamil expectations of Tamil women. I did. It’s the operating system installed at the factory and reinforced by the world around me that benefits from my labour. Over time, I’ve learned to deprogram and delete some of these expectations of myself so that I do not pass them onto my daughter.

We have a domestic roster so that labour is distributed fairly and without reference to gender. When I instinctively respond to a task, I try to challenge myself. I try to ask: “What would Annabel Crabb or bell hooks do? What would the Tamil Goddess Shankari do, rather than the Tamil woman Shankari?”, as well as, “What would my aunties do?” Like my aunties, I take enormous pride in feeding and tending to my children. It is their (and therefore my) love language. But I use their forced migration from Sri Lanka as an opportunity to interrogate and guide my actions.

For years, I’ve also reached into this cultural time capsule, learning so much from it to navigate the minefield of modern parenting. Through the emancipation of my own womanhood, I can finally see the wisdom of culture and can choose what to use.

My parents taught me that Hinduism invented feminism. (Sidebar: Tamils think we invented everything useful.) The scriptures tell us the female divine energy is equal to the male divine energy, and together these two halves form one whole. I am named after the Supreme Goddess, Shankari, who can create and destroy worlds as effectively as any god. This is the catechism I try to teach our children, our sons more so than our daughter because she already knows this.

One of the first prayers Hindu children, both girls and boys, are taught is Maathru Devo Bhava, Pithru Devo Bhava. Your mother is your God. Your father is your God. First your mother. What she does and who she is is revered. My father, a feminist and a Hindu, taught us this prayer. My mother, a feminist and our primary parent, role-modelled it. The positioning of the word “mother” gives it power in an inherently patriarchal world order that too easily makes invisible the contributions of women. It is not wordplay, it is a tactical reminder articulated thousands of years ago. I remember it well.

I’ve grown up watching Tamil people survive hardship – persecution, war and migration. They work hard to move large extended families to safety. They navigate new countries and cultures, retrain and redo qualifications in new systems. They don’t give up. The men and the women simply do not give up.

Tamil culture has taught me I am born into a community – an ecosystem – of family and friends, whose ties go back generations to a place that future generations will never regard as home and are unlikely to regard as homeland. However, wherever we are in the world, somehow we know each other, we belong to each other, and we help each other. I am never alone. My children will never be alone.

In diasporic community life, social mores and gender power eventually changed, in part because Tamil parents were telling their teenage daughters there was space for them in surgeries and wherever else they wanted to be, and mostly because their daughters (at every age) were claiming space for themselves.

In high school, things also changed. I graduated Year 12 with the same girlfriends I made in primary school. We hid in the library and created imaginary worlds. We learned how to assert ourselves in the real one. They believed in me then as now. We still talk about the Dune adaptation, the disappointment of Johnny Depp, our jobs, children and partners, our shared past, hopes for the future and everything in between. It is a lifelong bond.

The first thing I learned about womanhood was from an ancient religion and a loving family. Women are powerful – we are worshipped, feared, loved and respected. The second thing I learned about womanhood was from other girl-women – I needed to put my armour on to go to high school, and friends are everything. I’m grateful for all those lessons.

Big Ideas

The stories Trent Dalton is most proud of

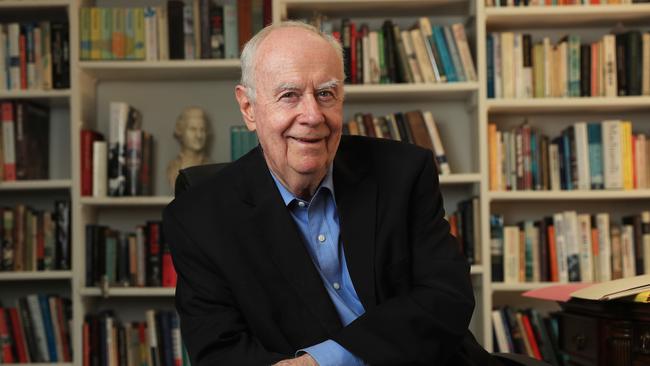

For 23 years, as a working journalist, I have been documenting Australians who simply refuse to succumb to whatever pervading darkness threatens to blacken their light. These stories are the keepers.

The trendy disparagement of science is un-Australian

Richard Scolyer and Georgina Long faced the worst possible scenario when Richard was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer. The melanoma researchers fell back on their medical knowledge to make a brave decision.

The turning point for all strong women? It’s not motherhood

It’s the pain and confusion that is my strongest memory of the worst year in the lives of all women, I’m sure. It was my first insight into the complexity and competition of womanhood.

The balance is broken: What now for democracy?

Radical shifts in social order; technologies that shape as foe rather than friend; erosion of faith; an end to truth and facts. The strength of our good society is about to be put to the test.

‘No one is disadvantaged just because they are Indigenous’

No meaningful change comes from selling ourselves short through guilt politics. It comes from understanding our history in its entirety.

Ideas are the source of all power in human affairs

Political power may grow out of the barrel of a gun but it is an idea that compels someone to pull the trigger, to raise an army, to start a war.

There is no choice: a Holocaust survivor’s view of courage

A difficult choice is speaking out against the populist but morally reprehensible behaviour of the crowd. If the tipping point between democracy and anarchy is to be avoided, we, you and I, need the courage to fight for our democracy.

What 1184 days’ jail has taught me about liberty

The Australian journalist who was detained for more than three years in China reflects on the true value of freedom.

60 most influential people of the past six decades

To celebrate The Australian’s 60th anniversary, this masthead has brought together a list of those who have had an impact on all our lives.

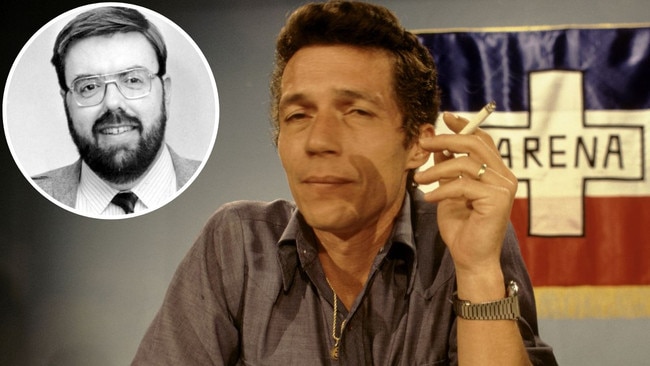

Cold, furious: The most evil man I have ever met

Getting to interview this man was challenging. He hated ‘gringo’ journalists and had vowed he’d never talk to one again. All of my peers warned me he goes crazy if you ask him about the death squads. But I had to try.

As a teenager, I vividly remember my father showing me the door of the family surgery. There was a sign that bore his name, my mother’s and their medical qualifications, earned despite ethnic conflict, forced migration and the challenges of a new country. He said, pointing to the sign, “There’s space for you, too.” My mother smiled and nodded her agreement.