The balance is broken: What now for democracy?

Radical shifts in social order; technologies that shape as foe rather than friend; erosion of faith; an end to truth and facts. The strength of our good society is about to be put to the test.

The pace of life is intensifying. Everybody is subject to the tyranny of the present. The rapidity of social change is empowering yet demoralising. The risk is that cultural fractures will only deepen.

Democratic politics with its parliamentary traditions and lengthy deliberations was not made for this emerging world.

That is a frightening idea. Yet it is best seen as a challenge for our better judgments. Australia’s record as a vibrant democracy, a healthy economy and a dynamic multicultural nation should invest us with confidence for the future. What does the next 60 years of The Australian newspaper foretell?

It points to a 21st century narrative of escalating technological change, greater economic and social fragmentation, a contest of moral and intellectual ideas, and an age defined by the contradiction between immense opportunity and deeper risk.

The stakes involved in human life will become greater. Can nuclear war be prevented? Will global warming impose intolerable restrictions? Will Western democracies sink into domestic disturbances? Will technology’s gains overshadow its negatives for human life? Can the next pandemic be effectively beaten? Can national rivalries be contained short of destructive wars? How will the world manage tensions between entrenched secularism and religious faith?

The call upon individuals will require greater imagination, personal courage and social responsibility. Technology will deliver economic progress, but the bigger job is achieving levels of income equity that underpin a good society. Liberal capitalism will be on trial – its record since the 2008-09 global financial crisis has been inadequate with massive inequalities and the loss of trust in political and corporate elites.

The social challenges will be akin to a hurricane and without precedent in human history. American social psychologist Jonathan Haidt recently described how childhood has been reinvented, for the worse, by Big Tech. In his book The Anxious Generation, Haidt outlines the rewiring of childhood, saying technology has harmed young people and society, exposed children to dangerous content, undermined their autonomy and rearranged their lives – in the interest of profit and tolerated by politicians.

But the future threat to the social order runs deeper. Haidt warns “it’s hard for citizens to play their role in a democracy when we cannot establish shared facts” and offers the dire assessment that “I don’t think we will again have shared facts or shared truth”. What is the future of rational discourse to resolve differences? The risk is that persuasion dies and is replaced by technological intimidation.

The challenges will be material and spiritual. Pivotal to the future is the question: what do we believe, and what does Australia believe? A nation without belief is a nation in trouble. The task is to ensure multiculturalism, now fundamental to Australia’s identity, becomes a unifying and not dividing theme. The present upsurge in anti-Semitism – with one group of Australians preaching hatred and exclusion to another group of Australians – is a warning about the future and what needs to be curbed or eliminated. “Strength in diversity” must become the guiding slogan.

Australia will face the fraught task of dealing with a largely post-Christian future. At present there is almost no discussion about its ramifications. The 2021 census revealed a nation where religious decline had been precipitous, with less than half the population identifying as Christians. The numbers had virtually fallen off a cliff – from 88 per cent of the population in 1966 to 52 per cent in 2016 to 43.9 per cent in 2021. Those professing “no religion” had risen to 38.9 per cent, nearly two-fifths of the country.

For some, Australia is becoming a nation of secular modernity; for others, it is regressing to indifferent paganism. It was the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche who argued liberal society operated on assumptions derived from Christian morality. “Christianity is a system, a whole view of things thought out together,” he said. “By breaking one main concept out of it, the faith in God, one breaks the whole.”

Is this to be our fate? Might there be a Christian revival? Or will Australia find a new source of spiritualism that denies the drift to narcissistic individualism?

The social contract in Australia – and other Western democracies – must be renewed. That demands a new settlement between liberal capitalism and liberal democracy. Capitalism for the few will mean a failed society. Democracy can only thrive with a model of capitalism that works for the entire community. The story of the past decade has been unsustainable wealth and income increases for the top 1 per cent.

That constitutes a challenge for Australia and all Western democracies. It is made urgent by the long-run alternative model of authoritarian capitalism now spearheaded from Beijing. Its epic propaganda has it that liberal democracy, along with American power, has seen its best days and is on the pathway to decline.

This question will be resolved in the next 15 years, with decisive consequences for the world. Much depends upon whether the United States, the leading exponent of liberal capitalism, can pull off the double act: get its own house in order and demonstrate a superior economic model to China. Australia, and the world, will be caught in this wash.

In a strategic and psychological sense Australia is tied to the US, more deeply than people realise. These bonds have intensified since the Howard prime ministership. They scaled a new peak with Scott Morrison’s negotiation of the AUKUS agreement involving Australia, the US and UK to equip Australia with a nuclear submarine capability, with deliveries into the 2050s – a bipartisan position now under the carriage of the Albanese Labor Government.

Deeper technological and defence-force integration between Australia and the US is likely to run for decades, with strategic dividends for Australia but greater exposure to the vicissitudes of US policy and the prospect Australia will be a US alliance ally in any military conflict with China. That means Australia has a critical interest in ensuring US-China rivalry can be contained short of open conflict, a situation that would be a disaster for the region and the world.

The quality of future US political leadership will be of paramount concern for Australia. At the same time, Australia will assume more responsibility as the metropolitan power in its region of the South Pacific. The central task for foreign policy will be management of China relations, since China will remain Australia’s major trading partner into the indefinite future while aspiring to become the regional hegemon – an outcome fraught with risks for Australian sovereignty.

Nationalism, state power and government intervention in the economy are the emerging dominant narratives. In the West, public scepticism of big business runs deep. The Biden administration has changed the direction of US policy, tying renewable energy and security against China into an era of resurgent state power and big-spending government. The 50-year phase of free markets, globalisation and the Reagan-Thatcher legacy is heading into historical eclipse.

Daniel Henninger in The Wall Street Journal recently said: “What we’re seeing is the inexorable rise of state capitalism, a system that deploys the state’s authority and money to force acquiescence to its version of social organisation.”

In his recent book The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism, Financial Times economics editor Martin Wolf said: “The health of our societies depends on sustaining a delicate balance between the economic and the political, the individual and the collective, the national and the global. But that balance is broken.” Wolf said liberal democracy and global capitalism “that were triumphant three decades ago have lost legitimacy” – a far-reaching challenge to Western nations.

Australia has a dual role in the coming century. It needs to enhance its success and offer a model to other nations. Indeed, this has always been Australia’s purpose. It has a rich and deep tradition on which to draw.

Democracy took root in Australia as fast as any nation on earth. That was our legacy from being a British colony founded in 1788 after the American Revolution and the year before the French Revolution. With no aristocratic class as an obstacle, Australia became a democracy before Britain, achieved its nationhood by a democratic vote of the people, and avoided the internal disruptions that have plagued other nations such as the US.

But the challenges of the 21st century are unprecedented. They will test the resilience of Australian democracy, the strength of its political leadership and the relationship between the elites and the people. What is needed, more than ever, is the quality of Australian Exceptionalism – those special ingredients that have made Australia so successful and which demand renewal for the coming epoch.

What might that epoch bring forth?

The transition from the industrial age to the digital age will frame much of the future course of Western and Australian politics. The technological story is riven with a paradox – it empowers each individual as a personal communications centre, yet it constitutes an unprecedented invasion of the human mind by the Big Tech companies through their phones, social media and artificial intelligence.

In this world, human beings are the product. Several years ago, billionaire investor George Soros warned that Big Tech was undermining open society and threatening human integrity: “Something very harmful and maybe irreversible is happening to human attention in the digital age. Social media companies are inducing people to give up their autonomy.”

In January this year Soros went further, warning of the “mortal danger” of China’s Xi Jinping deploying the instruments of artificial intelligence to control the behaviour of citizens in a totalitarian state. Offering an alarming diagnosis, Soros said: “We can be sure of one thing: AI helps closed societies and poses a mortal threat to open societies.”

Democracies will need to counter malign actors using AI to disrupt and corrode fair elections and open debate. Every democracy, including Australia, needs to be on the cutting edge of this struggle, assessing not only the potential damage from AI, but also its potential gains from data sorting, government programs and policy efficiencies.

This suggests an emerging world of deeper complexity – the domains of work and recreation, truth and fantasy, creativity and imitation, will become more fused and blurred. The upshot is likely to be a more fractured politics, with more pluralism, single-issue campaigns, massive struggles over information and misinformation, shifting alliances and the prospect the major parties of government in Australia – the Coalition and Labor – will come under more pressure and lose more support. The shape of government is sure to change.

Consider that at the 1949 federal election, the major parties won 96 per cent of the primary vote – testament to the conformity of the industrial age – while at the 2022 election they were reduced to 68 per cent of the primary vote. It was a 70-year period, but that’s a massive trend. It has changed our democracy, but if the trend continues, it points to a greater change in coming years.

Democracy gave great status to political parties, but as democracy evolves, the structure of political parties will change. Former prime minister John Howard says Australian politics has evolved to a 30-30-40 model. That means the major parties can each rely on only 30 per cent of the vote, while 40 per cent of people float among the main parties, smaller parties and independents.

There are two reinforcing dynamics at work: the main parties are less representative of the country, and the country has changed, making it harder for the parties to be representative. Australia, like other Western societies, is becoming a more culturally fractured nation. That’s because our shared values are being torn apart. The contemporary narrative is disagreement not only over tax and spending – the agenda of economics – but the core cultural questions concerning life, death, education, human relations, faith and personal responsibility.

Given politics is downstream of culture, that suggests a more turbulent politics. The social task – the challenge for human nature – will become the successful management of disagreement. Current omens are not encouraging. It will require the rediscovery of tolerance, which is the key to the liberal order and a stable society, a task that should not be beyond us.

In many ways Australia’s “make or break” transition is to clean energy. If this is driven by progressive climate ideologues the future will be grim, disruptive and dangerous. Australia has been a beneficiary for decades of fossil fuel-based cheap energy – that demands a transition where the balance is struck between environmental and economic interests. Shutting down old energy ahead of reliable clean-energy generation will be the hallmark of unforgiving political folly. If there is a serious risk facing the nation, misjudging the energy story is it.

Despite vast changes, core truths will remain: the first truth is that the good society needs the good economy. For Australia, that means a better productivity performance to run in parallel with its immigration policies. Economic growth is not enough; the engine of productivity is essential to drive higher wages and better incomes. That means an economy that is flexible but competitive, able to shift to new areas of comparative advantage.

The second truth is that the good society depends upon its family life. Families will vary in nature, shape and size, but the socialisation of children – from the home to the classroom to the playing field to their understanding of virtue – is the ultimate factor in deciding what happens to our democratic politics.

Big Ideas

The stories Trent Dalton is most proud of

For 23 years, as a working journalist, I have been documenting Australians who simply refuse to succumb to whatever pervading darkness threatens to blacken their light. These stories are the keepers.

The trendy disparagement of science is un-Australian

Richard Scolyer and Georgina Long faced the worst possible scenario when Richard was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer. The melanoma researchers fell back on their medical knowledge to make a brave decision.

The turning point for all strong women? It’s not motherhood

It’s the pain and confusion that is my strongest memory of the worst year in the lives of all women, I’m sure. It was my first insight into the complexity and competition of womanhood.

The balance is broken: What now for democracy?

Radical shifts in social order; technologies that shape as foe rather than friend; erosion of faith; an end to truth and facts. The strength of our good society is about to be put to the test.

‘No one is disadvantaged just because they are Indigenous’

No meaningful change comes from selling ourselves short through guilt politics. It comes from understanding our history in its entirety.

Ideas are the source of all power in human affairs

Political power may grow out of the barrel of a gun but it is an idea that compels someone to pull the trigger, to raise an army, to start a war.

There is no choice: a Holocaust survivor’s view of courage

A difficult choice is speaking out against the populist but morally reprehensible behaviour of the crowd. If the tipping point between democracy and anarchy is to be avoided, we, you and I, need the courage to fight for our democracy.

What 1184 days’ jail has taught me about liberty

The Australian journalist who was detained for more than three years in China reflects on the true value of freedom.

60 most influential people of the past six decades

To celebrate The Australian’s 60th anniversary, this masthead has brought together a list of those who have had an impact on all our lives.

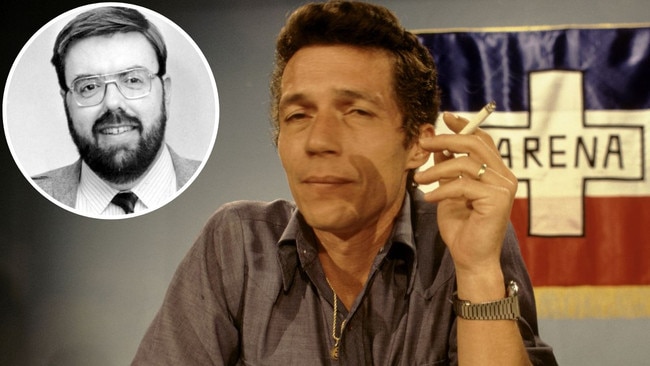

Cold, furious: The most evil man I have ever met

Getting to interview this man was challenging. He hated ‘gringo’ journalists and had vowed he’d never talk to one again. All of my peers warned me he goes crazy if you ask him about the death squads. But I had to try.

The epic political challenge of the 21st century is not only to show democracy still works, but also to keep democracy alive as the functioning model of our contemporary societies. Despite our guaranteed technological advances, our lives and communities cannot progress without viable democratic systems.