After the year from hell, Mick Fanning confronts his traumas

In a single year he lost his marriage and his brother, and suffered a terrifying shark attack. Now Mick Fanning has found a way to confront his traumas.

The nightmare is mostly the same every time. He’s back in the water on his surfboard and he’s waiting for a wave and he knows it’s Jeffreys Bay, South Africa, where all the madness began in 2015 and if he knows where he is in the dream then he knows what’s coming. Death. A splash behind him because that’s how it happened in real life. He turns around on his board and what he sees is the end of the ride. The end of all good things. A finale to an impossibly full life of only 39 years. The most brutal conclusion imaginable wrapped inside an ocean monster six metres long, weighing two tonnes, with an open mouth that is red, the colour of blood, and white, the colour of teeth.

And then he wakes and he realises he’s still alive. Still in one piece. Same ol’ unassuming, uncomplaining, knockabout, sun-bleached Gold Coast surfing genius Mick Fanning, flat on his back and sucking deep breaths in the darkness of early morning, sweaty head full of dreaming, beating heart too full of muscle remembering.

“I mean, it’s like I’m in the actual position I was in,” Fanning says. “It’s a reality dream. You sort of learn your body can do so many things to make things real and not real and I just had to learn, ‘OK, that moment’s been done. It’s not real. These dreams are just coming back’.”

He shakes his head in the cool winter air of Coolangatta, shivers with his hands in the pockets of a black winter coat, seated at a cafe table beside the footpath of a bustling post-morning-surf dining precinct. “I still have this PTSD where, if people splash behind me, it freaks me out,” he says. He chuckles when he says this. It’s not the laugh of a man trying to put on a brave face. It’s the laugh of a man trying to make sense of the absurd; a man grappling with a trauma that he realises he avoided confronting for close to five years.

A local couple stroll past the cafe and a man – mid-50s maybe – lets his partner walk on as he stands on the spot and shamelessly stares at Fanning, who is eating his breakfast and talking quietly about his vulnerabilities. The man, standing one metre away, smiles without saying a word and settles into his staring, props his foot, rests his hand on his thigh. He stays like this for 30 or 40 long seconds until Fanning raises his head and gives the stranger a warm smile. “How’s it goin’?” Fanning nods, politely.

“Good, how are you?” the man smiles, shaking his head with slow-dawning awe, as though he’s looking at the Mona Lisa and she just lit a cigarette before his eyes. “Good,” Fanning says.

The man does not move, does not stop staring. Ten more long seconds before, mercifully, the man’s partner snaps him out of his apparent stupor and drags him on along the footpath.

“Sorry,” the man says, shaking his head, coming to his senses. “Goodbye.”

“No worries,” Fanning says, waving.

“That happen often?” I ask.

Fanning shrugs his shoulders. He doesn’t say no. Call it the Mick Fanning effect.

“Who you interviewing in Coolangatta?” asked a young soldier at a Covid-19 border checkpoint not far from here. “Mick Fanning,” I said.

“Duuuuude!” the soldier said. “That’s one helluva flex!” Then the soldier punched his open palm in tribute to the central figure in the greatest pub story ever told. Mick Fanning. The bloke who punched a great white shark and lived to tell the tale.

Billboards and TV ads turned that moment into a punchline. In truth, it was a near-death experience that his mother, Elizabeth Osborne, believes will be forever tied with a leg rope to deeper, more complex traumas her youngest son experienced in 2015, the toughest year of his life. She believes the dreams are tied to that year, too. And the dreams are about more than great white sharks.

The retired three-time world champion – the man many pro surfers consider the most gifted turner of a board to ever ride one – forks through a plate of eggs and smashed avocado. This is his neighbourhood. This is home. A parking ranger with a bag of dog snacks gives a treat to Fanning’s best friend at his feet, Harper, a Belgian Shepherd- black Labrador cross. Fanning offers a hearty thanks. Then softly, philosophically, he unpacks the legacy of that mad day in Jeffreys Bay, July 19, 2015. The J-Bay Open. The final of the sixth event on the World Surf League Championship Tour that Fanning felt certain he was going to win.

Elizabeth Osborne was back home in Australia watching a live feed of the final on TV. Four minutes into the final she watched a huge shark surface behind her son. As Fanning punched and kicked instinctively at the shark, a gasping and petrified Elizabeth reached for the screen. A mother’s instinct. No sense in it beyond unconditional love. She was trying to reach inside the television and pull her boy out of the water. Because she’d lost one son already. Mick’s older brother, Sean, who died in a car accident; the boy she could still see clearly in her mind teaching Mick to surf on a pink boogie board under the Missingham Bridge at Ballina, northern NSW. “I just thought to myself in that moment, ‘No, the universe can’t be this cruel, I’ve already lost one son’,” she recalls. Months later, she watched a KFC commercial parodying the shark attack. A Fanning lookalike raising a great white triumphantly above his head as he casually surfs a right break. Some twisted link between her son’s misfortune and the “crunch” of a new chicken burger. The ad made Elizabeth physically ill.

“I didn’t realise how big of a deal that moment was even the next day,” Fanning says. “All these people are trying to do interviews with me and I’m like, ‘I’m good, I’m good’. I actually had to go to the airport but then people from CNN and places like that show up, ‘Oh, can we do an interview?’ I’m like, ‘I can’t, I’ve got to go to the airport’. And it all started dawning on me as we were flying home.”

A thought clear as day. No matter what I do, for all that I’ve achieved in my sport, I will be remembered for that shark.

“I was sitting next to a lady on the flight home and she’s like, ‘Did you hear about that shark attack in Jeffreys Bay?’ I said, ‘Oh, yeah’, and she didn’t realise and then she peeked at the paper and there I was on the front page and she looked over and went, ‘I’m so sorry’.” And he wasn’t sure if she meant sorry for the moment that just happened or sorry for the storm that was to come.

“The media scrum in Sydney was just next-level,” Fanning says. “I wanted to just hang out and be with family and friends and sort out what was going on but I couldn’t even leave my house. I had live television crews at the front of the house and then for a month or so I had paparazzi following me around. It was just stupid.”

Walking through another airport he was stopped by an old man he’d never met before who crystallised his new-found lot in life. “This old dude, I don’t know if he’d ever been to the beach in his life, he’s like, ‘You’re the shark guy’.” But he didn’t want to be the shark guy. Nobody wants to be the shark guy. Fanning sought advice from a friend, David Gyngell, former Channel 9 CEO. He asked Gyngell why there was so much interest in that moment. Gyngell summed it up with a single word. “Sharks,” he said. Then he summed it up with another word: “Ratings.”

“Gynge was just like, ‘Look, mate, it’s unfortunate but every time you bring up the word “shark” people are so attracted to it’. He sort of put it to me that way and that was a good thing where it’s like, ‘OK, well, I’m not going to take this personally’. Let’s just get through this period.”

Fanning granted 60 Minutes an exclusive insight into the shark encounter, hoping it would quench the world’s thirst for details. And the funny thing about that is, he says, it was watching that 60 Minutes footage again more recently that triggered the early morning nightmares. “I thought I was doing pretty good,” he says. “And then I watched this footage. There was a camera coming up from behind me and that sparked it all again.”

Shark POV, the cameraman’s shot list might have said. Apex predator point of view. Shark cam. All stalker-like and moody and dangerous.

Fanning might have howled at the enforced drama of it all if his heart wasn’t beating so fast. He knew in that moment the story of Mick Fanning and that great white shark wasn’t over. He’d left that moment in Jeffreys Bay behind but it hadn’t left him. There was healing to be done. There was work to be done. “And you just really have to work on these things,” he says.

It’s winter 2020 and even in the single biggest news year of 21st-century Australia sharks are still stealing headlines. On the day we’re talking, surfers across Australia’s east coast are reeling from four shark attacks in the past five weeks. A 15-year-old died after being attacked at Wooli Beach on the NSW north coast. Further north, a 36-year-old man was fatally attacked while spearfishing off Fraser Island. Off the notoriously shark-prone coast of northern NSW – where Mick Fanning’s older brothers first showed him how to surf – a 3m shark fatally attacked a 60-year-old man at Salt Beach, near Kingscliff. In one of the more alarming incidents of shark attack on record, a 10-year-old boy was dragged from a fishing boat by a suspected great white shark off Tasmania’s north-west coast. Miraculously, the boy survived after his father leapt into the ocean after him, scaring the shark away.

With every attack, Mick Fanning has heard a new and speculative take on the motivations and movements of sharks from beachside surfers he’s known all his life and total strangers who never hold back from sharing their insights. Wild conspiracy theories from 10-year-olds. Questionable accounts from salty 80-year-olds with longboards under their arms telling him why that South African shark singled him out in his year from hell. He heard enough of these opinions along the way to realise each one had been formed and influenced by each individual’s relationship with the ocean and the creatures that call it home.

“It’s a matter of what sort of encounters you’ve had,” he says. “Some people are like, ‘Cull them’; other people are like, ‘Just leave them, they’re in their habitat’. Some people are split down the line where they’re like, ‘Oh, if there’s a bad one, maybe investigate that one bad one and take it out’.” He shakes his head. “It’s just a real touchy subject... Everyone’s got their own opinion. I, personally, didn’t know exactly how I felt about it. And I decided I had to work on that.”

For the past year or so he’s been travelling the world with a filmmaking team, talking to world- leading shark scientists. What’s emerged from all that globetrotting field work is a two-part National Geographic documentary called Save This Shark that’s as much about exploring the wondrous evolution and ecology of sharks as it is about the deep emotional business Mick Fanning had left unfinished since 2015. “Mick didn’t actually say at the beginning whether he liked sharks or didn’t like them,” says producer Michael Lawrence. “He didn’t tell us what he felt. We just started the journey and we followed him all the way through.”

“I wanted to go in clean slate and just ask the questions,” Fanning says. “I didn’t have any agendas. It was just about, ‘Let’s get the real story across and see what’s actually happening out there’.”

The documentary sees him join research trips with scientists and shark conservationists across the world. He explores the work of Dr Neil Hammerschlag, director of the University of Miami’s renowned Shark Research and Conservation Program, debunking common shark misconceptions, measuring impacts of human behaviour and climate on shark populations. Groundbreaking shark ecologist Dr Charlie Huveneers from Flinders University takes him cage-diving with great whites off Port Lincoln. If Fanning had any lingering fear of sharks after the encounter in J-Bay then he faces them head on, nose-to-nose, in the documentary. Other scenes see him swimming cageless and free with tiger sharks and hammerheads. It’s harrowing to watch at times, akin to observing someone cure their fear of heights by hanging from a high-rise window. In one unsettling moment Fanning finds himself surrounded by five deadly tiger sharks approaching from too many terrifying black corners at the bottom of the ocean. “Pretty weird,” he says. “There was this one called Butt Face. For some reason, he just kept coming at me and I had to push him off four or five times. And this was no little dream sequence.”

With each dive in the film he emerges pale and shaken and then, eventually, reflective. Changed, even. “I feel like the more that you’re around sharks and the more you see them in their natural habitats, you sort of understand them a lot more.” All that the world saw in the J-Bay encounter, he says, was the 10 or so seconds when a great white shark met a surfer in the water. “You didn’t see it cruising for the 23 hours and 59 minutes of every other part of its day. So, yeah, it’s good to understand them and good to just watch them and watch the way they react to things.”

Make no mistake, he saw the power and terror of sharks down there, too. His own deep diving research makes him laugh now at the perceived heroism of his attempts at punching the J-Bay shark. “I was so insignificant to that shark,” he says. “I try to explain to people that when a shark wants to do something, it doesn’t matter what you do. People say, ‘Punch this or punch that’. Bullshit. It’s pretty much doing whatever the hell it wants to do and if you get away from it, then you’re OK. You’re lucky. If it wants you, you’re gone.”

By the documentary’s end, viewers are left under no illusions as to which side of the shark debate fence Fanning sits. “They’re such magical, majestic and misunderstood creatures,” he says.

Deep creatures, he says. Intense creatures. Survivors over hundreds of millions of years of evolution. The most poignant moment of the doco sees Fanning travel to the Bahamas to dive with Cristina Zenato, a renowned shark conservationist sometimes mystically referred to as “the shark whisperer” and “the mother of sharks”. Fanning might have raised his eyebrows at such terms prior to sharing the bottom of an ocean with her surrounded by fully grown reef sharks, one of which he saw “calmed to sleep” by Cristina before she placed it in Fanning’s lap underwater like a sleeping baby, so still and comfortable in his arms that he was able to lean down and kiss it.

“I don’t know how she does it,” Fanning says. “There’s a few people in the world, they can kind of hypnotise them and put them to sleep. She learnt it 25 years ago from her mentor. It’s not really asleep as such, it’s kind of just sitting there, relaxed. Think of it as a cat sitting on your lap.” He shakes his head at the memory of that moment.

“Mick would come up after every dive and give us a little debrief in the boat of what he saw down there,” recalls producer Michael Lawrence. “But when he came up from that dive he just went inside and sat down alone. And everyone just left him alone for about 15 minutes.”

“I was processing,” Fanning recalls. “I needed to go through it and figure out, ‘OK, what just happened?’” He sits in silence for a moment. He doesn’t quite know how to articulate it in a way that won’t sound foolish but there’s no way around the truth of what he saw.

When he saw Cristina nursing all those reef sharks down there with such care and such know-how, all he saw was his own mum. He saw Elizabeth. “And it sort of felt like my childhood in a way,” he says. “Like watching my mum dealing with all of us kids growing up.” He saw his three older brothers, Sean, Eddie and Peter. He saw his sister, Rachel. He saw his whole life at the bottom of the ocean and he saw the worst year of it, 2015, the year that keeps returning to him in his dreams.

“You made me what I am, Mum.” Elizabeth Osborne has lost count of how many times she’s received that text message back from her youngest son. A text to her boy to congratulate him on another world surfing championship. “You made me what I am, Mum.” A text about him being named Australian surfer of the year for the ninth time. “You made me what I am, Mum.” A text about how proud she is of how he’s moved into retirement. “You made me what I am, Mum.”

Everything about Mick Fanning runs deep. He connects deeply to his friends. He loves his family deeply. He loves surfing deeply. He loves the ocean deeply because he knows how many times it saved him and he doesn’t mean the time he got lucky with the shark. He’s certain that deep feeling for the ocean contributed to his success in surfing. He’s certain the people he loves contributed far more. He remembers every last person who ever helped him along the way and he regularly cries at the briefest thought of these people. He feels deeply and when his heart breaks it shatters into pieces.

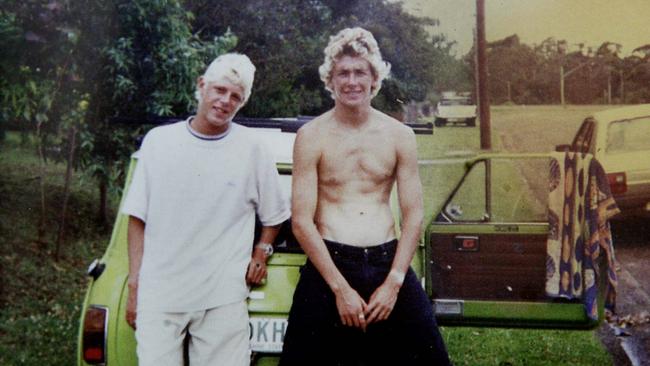

He was two years old when his mum and dad split up. He was 17 years old when Sean died in the car accident. They’d been at a party together. Mick walked home. Sean hopped in a car with friends and never made it home.

“He stayed in his room for a week when Sean passed away,” Elizabeth says. “He just sat in the dark.” His father, John, came over to grieve with family. “Mick just stayed in his room and wouldn’t come out for anybody,” Elizabeth says. “And then he finally came out one day and we were both in the loungeroom, John and I, and he just fell on us.” Tears well in her eyes at the memory of this. “I can see the beauty in that now,” she says.

The year 2015 began for Mick Fanning with the end of his marriage to Karissa Dalton. The J-Bay shark surfaced in the middle of that year and the year ended with the sudden death of his brother Peter at the age of 43.

We analyse our dreams at our peril but it’s not a stretch to see the recurring nightmares of that great white shark surfacing behind him as the past resurfacing to haunt Mick Fanning. “Oh, definitely,” Elizabeth says. “Definitely. It was a difficult year. His wife left him in February, and then the shark attack, and then Pete died. The whole year was a tragedy. When Karissa left, he didn’t tell the family. I knew, and it was terrible. He never told the family exactly how hard that was. He was absolutely devastated and it took him a long time to get over that. And then the shark attack was this terrible incident. It’s funny, in the scheme of things the shark attack was just an incident. But the rest of that year was a tragedy. There was so much in Mick’s life that was tragic. And, of course, then Peter passed away. He had hyperthyroid problems in his heart. Everyone tried to say it was a drug overdose but it wasn’t. Peter loved Mick to death. I had to tell Mick at 4am in the morning that Peter had passed away. He made me a cup of coffee. He was looking after me.”

The only reason Mick Fanning learnt to surf was to spend more time with his heroes, his older brothers. The universe declared he was going to be one of the greatest surfers who ever lived and then the universe took away two of the biggest reasons for him to surf.

When Elizabeth saw the documentary footage of her youngest son sitting peacefully underwater with the reef shark in his lap, she saw something deeper than a man investigating the strange behaviours of sharks. She saw a full-circle moment. She saw her boy healing himself in the most improbable way. Embrace the shark, she told herself, embrace the nightmare. Accept the nightmare, she told herself, accept the year from hell. “I cried in that moment,” Elizabeth says.

Fanning takes a deep breath at the cafe table in Coolangatta. “It was the toughest year of my life, personally,” he says. “I went through divorce, then had a shark attack and then, at the end of it, lost my brother.” He nods his head in silence. “Yeah, I was at the bottom,” he says. “I had nothing to give, to anyone or anything.”

A local woman passes the cafe with a dog of her own that inspects Harper’s rear end; the woman smiles knowingly at Fanning like they’ve been thrown into such an encounter before.

“Hello,” Mick says. “You well?”

The woman nods. “Baby here yet?” she asks.

“Nah, not yet,” he smiles. “Still waiting.”

In February, Fanning made public the news he was both engaged to and having a baby with his partner since 2017, Breeana Randall, a Californian speech therapist. “They met because he left a coat behind somewhere and she took it back to him and that was it,” says Elizabeth. “We were anxious at first, but Bree is such a beautiful girl.”

A fortnight after this chat in Coolangatta, the couple will welcome Xander Dean Fanning into the world, weighing 3.31kg. “Dada loves you beyond words,” Fanning will post on Instagram.

They’ll be beautiful parents, Elizabeth says. Xander will learn the values of hard work and discipline because Mick learnt these things the hard way. “Mick had nothing,” Elizabeth says. “Nothing. He was lucky to get a hand-me-down.”

“I guess, when it comes to my own kids, I’ll just be trying to teach them what I’ve learnt in life,” Fanning says. “I’m not going to have all the answers so I’m going to be doing investigation and learning with my kid along the way.”

He won’t force surfing on Xander. He won’t show him a single surfing video or trophy from the glory years unless Xander asks. He won’t show his kid the shark encounter, but he will share what he’s learnt about sharks along the way. Surf long enough in the ocean, he says, and you can sense when something’s not right in the water. There were many times in Fanning’s career when he sensed the presence of sharks. He always fought through his instinct to take flight and kept on surfing. He stayed in the water. Not anymore. Too much respect for the creatures. Too much respect for fate. “Trust your instincts,” he says. “You get a bad feeling, get the hell out of there.” Same applies to life, he says. Pick your wave. Know when to ride it and when to swim like hell away from it.

“The first 39 years of my life has been a rollercoaster with some incredible highs and some incredible lows,” he says. “I’m not sure what the next 39 years will be like and that’s good.”

As Fanning talks, a woman passes the cafe table, not noticing the three-time surfing world champion seated to her left.

“Hey, Mum,” Fanning says.

Elizabeth stops and beams at her son. She lives nearby. They hug. “How’s Bree?” Elizabeth asks.

“She’s good,” Fanning says.

“She’s ready to roll,” Elizabeth says, excitedly.

“The scans yesterday said [the baby is] in the right position,” Fanning says. Elizabeth cups her hands, barely able to contain herself.

They talk briefly about the future. How excited Elizabeth is to see the next phase of her youngest son’s life, the most enriching phase yet. “This is going to be a wonderful experience,” she says. “He’s going to make a great dad.”

She nods. “We had the agony,” she says. “The deep agony. We’ll have the ecstasy, too.”

They talk some more, then Fanning stands up and reaches into his pocket for his car keys. “I’ve gotta get going,” he says. He gives his mum another hug then grips Harper’s leash and starts to walk off. Elizabeth doesn’t take her eyes from her boy.

“Love you darlin’,” she says.

Fanning stops and turns around again.

“Love ya Mum.”

Save This Shark airs on National Geographic Australia, September 15.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout