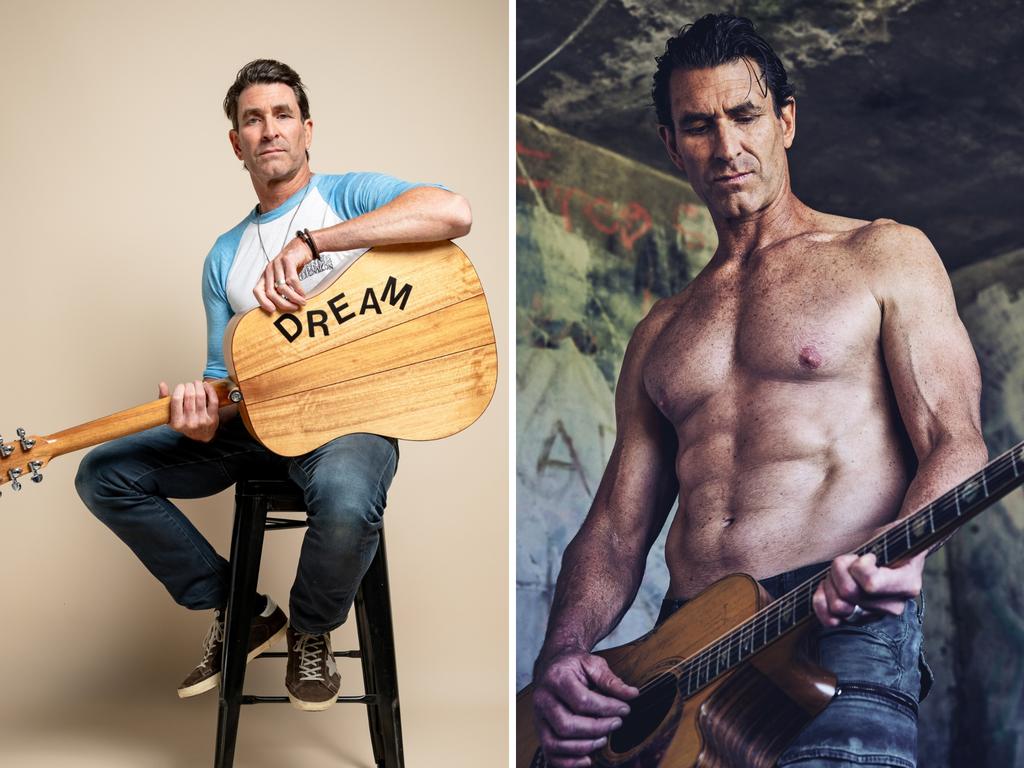

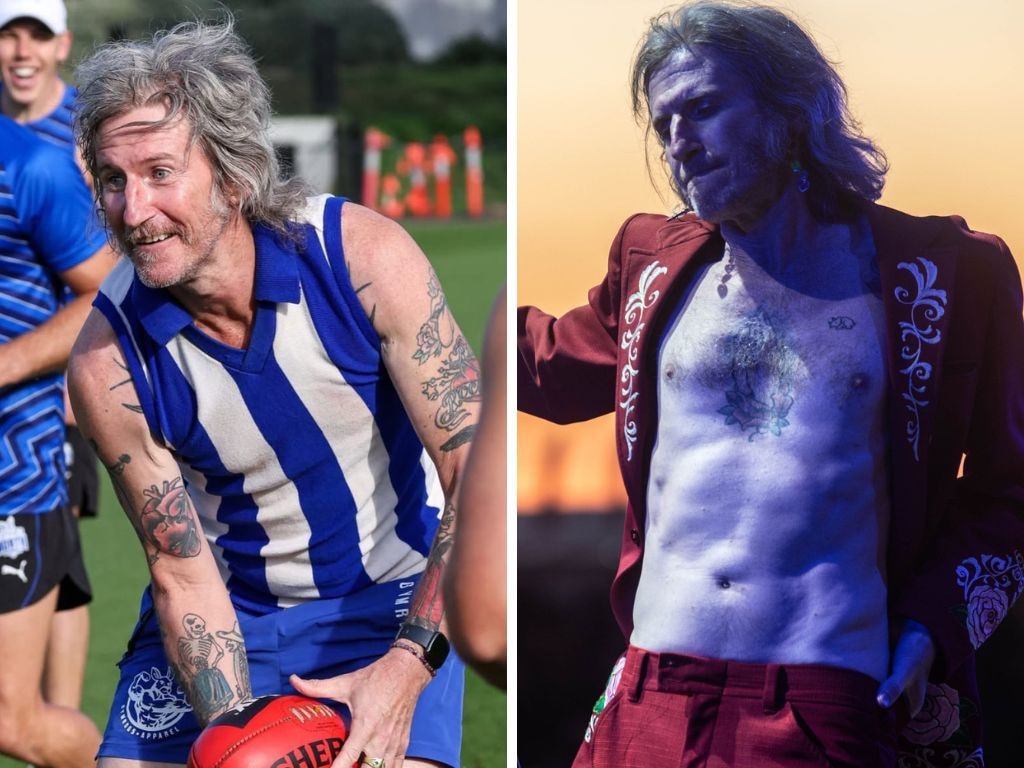

Jimmy Barnes talks addiction, chronic pain and meditating with forest monks

The rock singer, songwriter and author, 69, speaks on fitness, wellbeing, alcohol and drug use and managing severe pain on Cold Chisel’s most recent tour.

Singer, songwriter and author Jimmy Barnes, 69, speaks with The Australian about fitness, wellbeing, meditating with forest monks and managing hip pain on Cold Chisel’s most recent tour, as well as what he's learned about alcohol and drug use across his career, and how these themes coalesce on the songs of his 21st solo album, Defiant.

What was your relationship with exercise as a younger man, Jimmy?

I was always pretty fit as a young fella. Even when I first joined Cold Chisel (in 1973, aged 16), I was training and playing soccer all the time. I was a lazy striker; I was one of those guys who always happened to be in the right place at the right time, which is the story of my life, really (laughs).

My father was a boxer, so I did boxing as a young man; we used to run and work out a lot. When I joined the band, my working out became more club- and pub-based. A few years into Cold Chisel, I took up martial arts – so as wild as I was, I was also training at the same time. I actually stopped martial arts because I got really good at it. At the time, a Scotsman with a bad temper and a drinking problem wasn’t a good person to have a black belt, you know? (laughs) I thought I was better off to find a gentle thing to do with my time.

From there, I did yoga for a long time, I played golf, and did lots of walking and swimming. I’d done some injuries to my back through martial arts and jumping around on stage, so yoga was becoming difficult; for quite a long time now, I’ve been doing pilates – I have a reformer in my house – until I started having surgery for my hip. So I haven’t been able do it for about three years, but I’m literally in the process of getting back into that now. Over those past three years, I’ve been swimming; whenever I’m not recovering from surgery, I’ve been in the water. I really like the idea of swimming, because I like the meditative motion of it: you’re in your own head, there’s no distractions. It’s only you, and you’re in your mind. So I’ve always been reasonably fit, and considering the lifestyle that I’ve lived, that’s why I’ve been able to continue to do it for so long. I think that’s what saved my life, really.

Come to think of it, isn’t the title of your debut solo album a soccer term (Bodyswerve, 1984)?

Yeah, that’s where you lean one way and then you go the other; it’s a bit of “sleight of hand” sort of thing, if you’re trying to pass someone with a soccer ball. Bodyswerving was something I used to use socially when I was a young man in Cold Chisel, because quite often there’d be hundreds of people who just wanted to get hammered (with me) and you’d say, “Oh yeah, I’ll meet you at the bar” – and then you’d go somewhere else, so you’d bodyswerve them. (laughs)

All of the above might surprise those who’ve stereotyped you as a wild rock star who never gave a damn about your health – but clearly, that’s not true.

I had to do it to survive what I was doing to myself, living the lifestyle on the road. I remember touring America in the ’80s – in the height of the wild, wild days – and being on a bus for five or six hours overnight, and then being stuck at a venue all day, you’d just go crazy. Either that, or you’d drink yourself to death. We would literally arrive at the ZZ Top (show) or whatever gig we were playing, and then we’d train for four hours. I had a karate instructor with me who was a good mate of mine, Noel (Watson); we’d get up and we’d run miles, do bag work, we’d be sparring. So I trained hard, but at the same time I was beating myself up in many other ways, as well; (the exercise) was almost counteracting it, but I think that kept me alive during all that time.

What about the more modern term of “wellbeing” – what does that word mean to you?

Physical fitness and wellbeing are two different things. I think wellbeing is a lot more of a state of mind. Part of it’s about your body; now I’m much more in tune with wellbeing than I am with just fitness. These days, it’s much more holistic. Over the years, there was periods where I tried to look after my mental health, because I was struggling with it for so long. I would try to meditate, which was very difficult for me, because I was ADHD and bloody hyperactive. One of the things about meditating is that it allows you to process other thoughts; it’s like clearing space out of your hard drive, and then other things can go through, and you can deal with things. There’s a lot of stuff I didn’t want to have to process, so meditating was always difficult for me. But in 1986, I started meditating. There’s a monastery in Bundanoon (NSW) called the Sunnataram Monastery, which is (run by) Thai Buddhist forest monks. Because of (my wife) Jane’s Thai heritage, she knew this monastery, and I used to go out there quite a few nights a week and meditate with the monks.

They’d give you Dhamma talks, where they’d tell you how to deal with life, spirituality, all that sort of stuff. But then we’d meditate for an hour, and I found even just the act of sitting and meditating helped calm my nervous disposition, and helped take the edge off of all my worries. (Indian-American writer and speaker) Deepak Chopra is a dear friend of mine; he used to come to Australia, and I’d go sing at his conventions, and I spent a couple of weeks in Goa (India) with Deepak; we ended up meditating eight hours a day. I also went to northern Thailand, past Chiang Rai, and meditated with monks in caves, up in the hills.

Unfortunately, I didn’t do all these things at the same time; I’d either be doing that, or I’d be training, or I’d be drinking. These days, wellbeing for me is trying to encompass a bit of all of that stuff at the same time. I think it is about balance. I don’t want to be a saint, or a monk, or whatever – but if I can keep a good balance on being able to eat good food, and socialise with my friends and my family, and not be writing myself off, I think that’s all part of wellbeing.

Congratulations on your new album, Defiant, on which you’re singing beautifully, just as you were on the Cold Chisel tour last year. What’s your relationship with your voice today?

I’m a better singer now. I think the process of writing all these books – particularly Working Class Boy (2016) and Working Class Man (2017) – allowed me to break down a lot of barriers; a lot of things that were stopping me from dealing with my emotions and feelings. I’m not so traumatised anymore. Because of writing those stories and purging myself of all that stuff, it’s allowed me to be able to feel, and not be overwhelmed by feelings as much. When you’re singing, you want to find those emotions in yourself. In the past, when Don (Walker, Cold Chisel songwriter and pianist) wanted me to sing a song and wanted me to be angry, it was really easy for me to be angry. If he wanted me to be scared, it was really easy for me to be scared; if he wanted me to love, I could feel love. But the problem with it was, I would be overwhelmed by all those feelings, and it would take over. These days now, as a singer, I feel I can tap into those emotions; I can actually use the trauma of the past, and things that I’ve done wrong and right, to allow me to access those feelings a lot easier, which makes me a better singer.

In the latter half of that Cold Chisel tour late last year, I believe you were in pain from your temporary hip replacement. What helped get you through that?

Over the past three years I’ve had three hip replacements, all on the same side. The first one was really good, but unfortunately for me I got a staph infection; it went into my blood, my hip, my heart and also into my back. So within three years, I’ve had those hip replacements, a back surgery and open-heart surgery, and that was most of it due to the staph infection. Anybody who’s having surgery, the thing you’ve got to do is pay attention to the doctors and the physios: they tell you what to do. I tend to be a bit gung ho, and so I had to really fight myself not to do too much. But I’d get up the mornings and I’d do a series of exercises with rubber bands, with light weights and stuff like that, until I could get in the water. Swimming was the thing that got me through most of it, really. Once I was able to get in the water, then I could work my hip, work my joints, and still get fitness happening. Cycling is good; I bought a Peloton, which was a good thing, but it’s hard work. I much prefer swimming to riding the bike.

But because I was in so much pain on that Chisel tour, I had a physio on tour with us, and at that point I’d already got the staph infection in the first hip, and had it replaced with a temporary hip. In that, the ball joint was smaller because they were going to take it out again – and so the problem with that is, if I had moved, fallen or tripped the wrong way, I could have popped it out very easily, which would have been disastrous in the middle of a tour. There was nothing I could have done; I would have been in hospital. So every night I had a physio strap me up like a mummy. It was really heavily strapped, like a football player, to keep that hip in place and also to remind me so I didn’t turn or jump on it the wrong way.

Even in saying that, although it was strapped so severely, I still managed to jump on it a few times, because I’d forget in the middle of singing. The problem was, it was my left hip; when I sing, I lean on my front foot, and a lot of my weight is on that front foot. That’s how I engage my diaphragm; I’ve sung like that for 50 years. They were trying to get me not to sing like that, which was difficult. I tried singing off my right leg, but it was like having your shoes on the wrong feet, so I found myself constantly drifting back and singing on (the left). It was a good thing I was strapped up; the physio got me through that tour. And plus, it was so much fun.

It’s amazing to think that was all going on behind the scenes, and none of the punters had a clue you were in such a pained state.

It was pretty incredible, but you’ve got to remember, when you do a performance like that, there’s a lot of adrenaline involved. I’m nervous from four or five hours before a show, and the closer it gets to the show, the more my adrenaline’s running. By an hour before the show, I felt no pain; they had to nail me down to strap me up. I was ready to go. I was fine on stage, I could charge it – but as soon as the adrenaline started wearing off at the end of the show, when I’d walk off, it would start to hurt. At night, I’d go home, I’d have hot baths and be icing it. Then I’d be up the next morning to see the physio: get massaged, get strapped, and then ready for the next show. It was the same every day; it was a routine.

You’ve experienced a lot of pain in your life, and you’ve shared a lot of that with your audience through your songs, your books, and through interviews like this. What have you learned about managing physical pain, Jimmy?

They say some people have a high threshold for pain. I think I’m pretty good like that; I can push through when I have to. I think that just comes from stubborn Scottish genes. I’m defiant. (laughs) Hate to say it, but that’s one of the reasons why I called the record that. I’m pretty defiant and I find that when things hurt, I can tend to push through it, which is a good thing – but it also means you can do yourself an injury if you’re not careful. It’s a fine balancing line.

I think if you’re doing something you love, and it’s something you need to do and love to do, you’ll find a way to do it. For me, when I had the temporary hip put in after I got the staph infection, they said to me, “It’ll be six months until you sing”. I was literally on tour with Cold Chisel in seven weeks. (laughs) It was pretty intense, and they were all freaking out, but it was just because I had to do it, and I wanted to do it, and because it all happened out of my control, the last thing I wanted to do was let all the punters down, or the band down. So I just said, “No, I’m going to get through this”. I worked hard: number one was listening to the doctors. I did everything they said, and as soon as they said, “You could try and push a bit harder”, I did. But I didn’t push too hard, too early.

How’s the new hip feeling on stage so far?

I did one the other night, Blues on Broadbeach (May 18), and that was the first show since January. It was great until I came off, and I’ve been sore for two days, but I’ve been back in the pool this morning, and I swam 20 laps. I’m feeling a little stiff and sore, but it’s good. Because it’s the third hip on the same side, that means there’s a lot of scar tissue there; they said it’s going to take a little longer than normal. I thought I’d be up and all pain gone in seven weeks, but it’s probably going to take another seven or so. But I can time it, and loosen it up and exercise it, and I know all the right things to do, so that I can get through the upcoming shows.

I’m really dying to do the Defiant stuff (in concert). There’s a couple of reasons: one, because I wrote these songs especially for playing live. When I was writing the songs and constructing the record, I was thinking, “I want to do songs that I could just slot straight in my set”. The other thing is, a bunch of these songs I wrote while I was lying in the hospital bed. I was writing lyrics and even melodies into my phone while I’m thinking, “This is what I want to get out and do”. The songs mean a lot to me, so I think just the sheer will of wanting to be on tour, and wanting to do what I love, is going to help me get through it.

Your past alcohol and substance use is well documented – “the guy that I was back then”, as you describe it in New Day, the first single from Defiant. What’s your relationship with drugs and alcohol today?

It’s a thing that I look at and I wonder how I got through it, I really do. For me, because it was so entwined with trauma, pain, childhood abuse and all that sort of stuff, it was even harder to battle. I thought I could beat anything, and I thought “drugs will never run me” – but they overran my life, and took over me. My relationship with them is that it’s one of those things where, if I started taking drugs now, I’d be gone. One would be too many – and not enough, at the same time.

So I don’t take any drugs. I’m even wary of painkillers; when I was in hospital having heart surgery, they wanted to put me on (the opioid) Endone. After two days, I said, “No, I don’t want it”, and I took Panadol. I’m very careful with it. I drink whiskey very rarely now, just as a toast thing, as a Scotsman – but I can’t drink it (often) because it’s a slippery slope for me, as well. I just feel better in my head, and in my heart, if I keep away from it.

You’re also not the kind of guy to preach at anyone else about their own usage, right?

No, I don’t care what anybody else does. Everybody to their own – and listen, I’ve seen people out there who can take drugs and do all that, have a good time, control it and walk away from them. But I’ve seen a lot of people who do get damaged by them. If anybody asked me for advice, I’d tell them to avoid it.

I used to wear it as a badge of honour that I drank so much and all that sort of stuff, but I think that was really silly. It was this weird bravado thing that I had about beating my chest, because I didn’t like who I was. And the more I changed myself, the better I liked myself – but in the end, it just got worse and worse, so I didn’t like myself at all.

Anybody out there, be careful with them – but everybody’s different. I’m one of those people, I like being at parties where people can do what they want: they can take drugs, they can drink, they can do anything they want around me. It doesn’t affect me; I don’t feel like I’m missing out, and I don’t feel like lecturing anybody. (laughs)

Lastly: at 69, and with a bunch of major operations under your belt in recent years, is it fair to say you’re more grateful for the times of good health than at any other point in your life so far?

Oh, absolutely. I’m really thankful to all the people at the hospital. I was critical quite a few times there, with sepsis and the staph infection in my heart, and all that. I thought I was going to die a few times there. I’m really thankful that I had so much care and love, and I’m thankful that we have such great medical care in Australia; if I was in America, I’d be dead by now. I’m also thankful that I’ve worked out that it’s never too late to change, you know? When you’ve been hammering yourself for 50 years, you think, “What’s the point? The damage is done”. But every day I change, every day I get better, every day I feel better, and every day I’m stronger.

It’s never too late to change your habits; it’s never too late to change what you do, say sorry, and move ahead. You can always make a fresh start, and New Day is a song about that: every day, if you pick yourself up, you can say, “I want to change this and make it better”. It might never be the same as it was, or what you wanted. But it can be better.

Defiant is released on Friday, June 6 via Mushroom Music. Jimmy Barnes’ tour begins in Adelaide (June 7) and ends in Canberra (June 28). Tickets: frontiertouring.com/jimmybarnes

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout