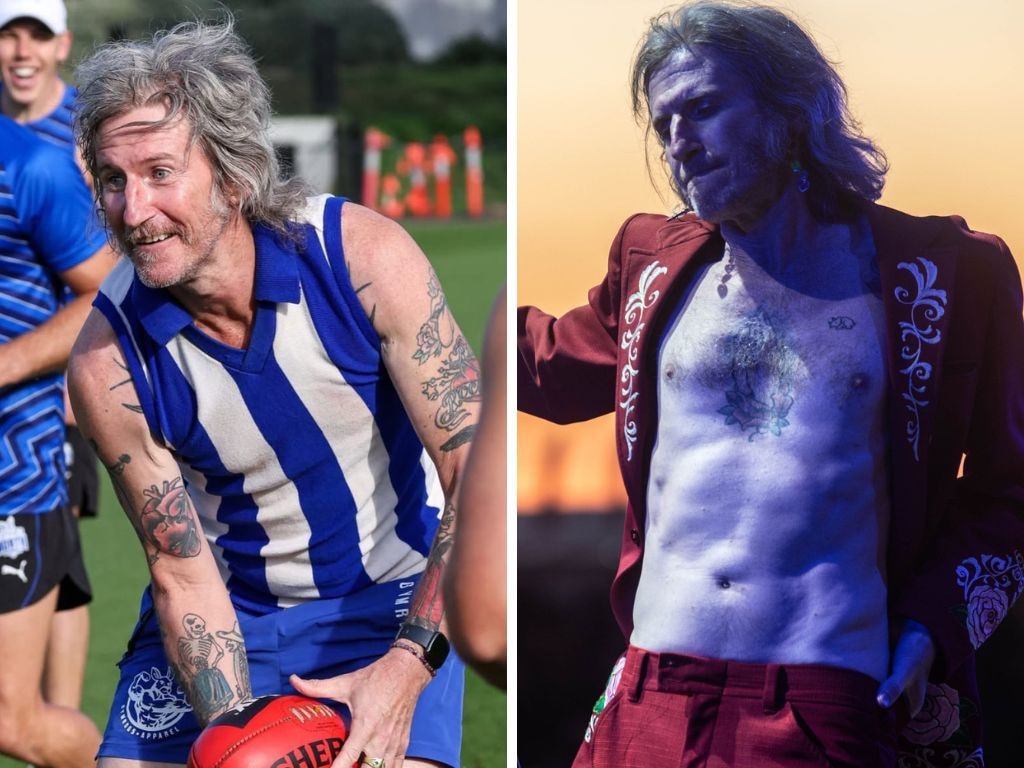

Pete Murray on health, fitness and life lessons from his dad’s early death

Ahead of an extensive solo acoustic tour, the award-winning singer-songwriter talks about pacing himself while on the road, admiring Paul McCartney’s longevity, overcoming career roadblocks and learning lessons from the early death of his father.

Pete Murray, 55, is an APRA Award-winning singer-songwriter based in Byron Bay. Ahead of an extensive solo acoustic tour, he talks to The Australian about pacing himself while on the road, admiring Paul McCartney’s onstage longevity, overcoming career roadblocks and learning hard lessons from the early death of his father.

Pete, you’re soon to undertake a 56-date national tour. What have you learned about how to take care of yourself while touring?

I think eating well and sleeping well are the two big things – and not drinking so much. I’ve done a tour before where I haven’t had any alcohol at all – not that I’m big drinker anyway – but it’s quite nice to have no alcohol at all when you’re performing. It’s the travel that takes it out of you: the long drives, the flights and the early mornings of getting up and going to the next place. Then you check into your hotel, do your sound check, come back and have dinner, play your gig at the venue and come back. You really don’t get any time to relax: maybe an hour before the show, but then you’ve got guests and friends that want to catch up with you, so it’s a very tricky time to do that.

Do you enjoy being in that rhythm of constant motion?

Yeah, it’s something that I’ve been doing for a long time now. I quite like being on the road; I like touring. Some musicians can’t stand it. I love performing. I think it’s great fun with the travel, getting out and about, seeing different places. But it’s taxing, and the negative things are that you’re away from family. That’s the tricky thing, I guess: you’re not there to help out at home. But it’s my job; that’s what I do. Years ago, I was looking for a job that would allow me to travel the world and earn money from it. That’s what this is, and I’m very fortunate to be doing music. It’s a very small percentage of artists – especially in Australia – that actually can make a living out of it. I feel like I’m very blessed that I can do that, and I don’t take that lightly any day. Whenever you’re touring, you want to be grateful that everything’s working well.

How will you pace yourself across those 56 shows?

This tour starts in early May and finishes in mid-September. It’s pretty much every weekend you’re performing: Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday, come home for three days, and then go again. You definitely have to pace yourself. Maybe the last weekend, I might allow myself to loosen up a little bit, have a couple of drinks and relax a bit. But before that, my biggest concern is losing my voice. I eat good food, and I try to go to the gym whenever I can as well. But I’ve always been that way: as soon as I get overseas, the first morning I arrive, I’ll go to the gym straight away at the hotel and do something. You just feel better when you’re doing it – keeping healthy and keeping fit – rather than not doing it.

In terms of exercise, what are you fond of?

I do weights training, but not heavy stuff; I kind of do it in a cardiovascular way, where I’m having short breaks in between reps. I might have a minute between each set, but I’ll keep going along. Your heart rate’s up while you’re working out, so you’re still getting some fitness out of it, and you’re also getting some strength as well. For me, that’s the best way: in 20 or 30 minutes, I can get in a really good workout, and then I’m done. You want to be basically in and out quickly, because time’s not on your side.

Do you play sport?

When I was younger, I did swimming, athletics, and then football: I played rugby league, then I played rugby union when I got a bit older. Athletics is probably my favourite sport. I used to run fours and eights [400m and 800m]. That’s super hard work; the 800m is the greatest race, I think, because it’s tactical, but it’s almost a sprint as well. It’s such a challenge. I used to love training for it, and that helped my rugby as well. When I came across to rugby, I was a chance of making the Australian Sevens team because I was so fit. I still had skills with the footy, but I was so much fitter than the other guys. I could go the whole game, whereas the others would start to blow up, so that was my advantage. But individual sports, I find, are great, because you can’t rely on anyone else. You’re the one that’s got to compete and win the race. It’s probably a bit more fun in a team sport, but I felt like doing the individual sport was more challenging and more rewarding for me, if you did have success.

In the 20-plus years you’ve been working as a well-known musician, you’ve always appeared to be fit and healthy. Has that been important for you to maintain?

Oh, definitely. I love sport, I still keep fit, and I think probably the reason why I’ve had some success in music is I’ve had the same mentality of what I did in sport: if you want to be successful, you’ve got to keep training. But there’s a love for that, too: I love feeling fit. I don’t like feeling unfit, and drinking heaps, I don’t feel good after that. My body can’t take it too much, which I’m sort of happy about. It’s the same philosophy going into music: you’ve got to work hard at it. That’s getting better at songwriting, but also just keeping fit and healthy. I always want to be that; I want to be playing on stage when I’m 80. It takes it out of you, doing that: Paul McCartney, at the moment, looks incredible. He’s 82, and he just did this massive tour. To see him still going at that age is pretty amazing. But I wouldn’t want to do it any other way. If I miss three days in a row from going to the gym, I feel like I’m losing out. I’ve gotta get there! [laughs]

What about the mental health side of things? How do you stay mentally fit while on tour?

I’ve always been fairly good at that. My dad died when I was 18; he was only 47. There were a few tough years for me there; I had to learn how to deal with that, move on and get things going. I find that you’ve got to talk to people if there’s any dramas with how you’re feeling. I think that’s probably the biggest problem that guys have: they just close up and don’t talk if they’ve got any issues. I like to talk if there’s something that’s bothering me; I don’t hold it in too much.

But look, I’m doing what I love, so in most cases, it’s all pretty good; pretty positive. I’ve had to work hard to get to that point. Even when starting music, that was a very hard, very challenging period of my life, trying to make music happen. I started quite late: I didn’t pick up a guitar until I was 22, and I didn’t record my first independent album until I was 30. I started to doubt everything that I was doing, and that was a very hard few years of trying to believe in yourself when you were thinking, “This isn’t going to work. What am I going to do now?”

During that time, when you were continually running into roadblocks with your music, what kept you going?

I’m glad you said “roadblocks”, because I use “roadblocks” all the time. Musicians have that, you know? I remember when I was mid-20s, I had some mates who were starting up a band, and they asked me to manage them, which I did for a while before I was doing my own [solo] stuff. I remember going to this managers’ forum with [industry association] QMusic in Brisbane, and the lady there – Rose, I remember her name quite clearly – she said, “Right there’s three things you need to be successful in the music business!” I had my pen and paper out, ready to write, and she said, “Persistence. Persistence. Persistence.”

It made sense, because no-one’s ever going to get people going, “You’re awesome! This is great! Come on through! This is going to happen!” That never happens. Every time, no matter who you are, lots of people are going to say “no” to you. “You’re too old. It’s not good enough. You don’t look pretty enough,” or whatever it might be. It’s that self-belief and it’s that persistence that you have to keep going with, to make this successful. It’s the guys who hit the wall and go, “I can’t do this anymore,” and they give up; there’s a lot of talented people that don’t make it in music. For me, I think it’s probably the hardest business in the world to try and crack. To have success in it is very difficult; to even have a career in it is even harder, so hats off to anyone that has a career in music.

I ended up getting signed to a label [Sony Music] at 32, so there was a few years there where I was going, “What am I doing? All my other mates are getting good jobs and good money, and I’ve got nothing.” I couldn’t even buy myself lunch. I’d be looking in the cupboard for a can of baked beans and a bit of pasta to try and put something together.

But when you get through that, I guess it makes the success more rewarding, because you’ve done it the hard way. There’s all these sacrifices you’ve made that people aren’t aware of; they just suddenly see that you’ve had success, and you’ve “instantly” done well. That’s the mental strain and the stress that everyone goes through, trying to make that happen. And it can be very depressing, because you’re on these highs and lows: you’ll play a show where there’s a great crowd there, and the next show you play, there’s no-one there, and you start to doubt: “What’s happening?”

Your chart-topping 2003 album Feeler, and its single So Beautiful, is what helped you break through to a national audience. Was that experience gratifying?

I struggled after Feeler. I just didn’t think it was good enough. It was just me that thought that; it was having all this success, and I still didn’t get it. I just didn’t know why people liked it. I liked playing the songs live, but couldn’t listen to the album from start to finish; I couldn’t do it. I remember getting a text from Darren Middleton from Powderfinger one day in about 2011 going, “Mate, I just listened to Feeler – what a great album!” And I was sitting there thinking, “Is it? Is this a good album? I haven’t even heard it.” I recorded it, but didn’t listen to it. And at that time, eight years later, I put it on from start to finish – and at the end, for the first time, I was like, “Wow, it’s actually a really great album”. I was struggling for a long time with that.

You mentioned that your father died at 47, when you were 18. What effect did that have on your health from that point on?

Oh, it was massive for me. Like I said, I’ve always been very healthy, but when that happened and he died, it was a real serious look at, “OK, I’ve got to be careful”. Because his father, too, had a stroke, so there’s something in the family here that we’ve got to be careful with. I’ve had my check-up, and I’m good; I’ve been told I should not die of a heart attack. Dad smoked for a long time; he gave that away, but his diet wasn’t the greatest. Having that hereditary heart disease in the family, he wouldn’t have been aware of the damage that’s happening to his heart – but I have been.

In a way, it was a real wake-up call for me, in a number of areas. He was working most of the time, so we didn’t get a lot of time to hang out together. Learning from that, I wanted to make sure that with my family, I have that time with them, and I could actually spend time with them; be a dad, but be a good friend as well, so that we’d have a great, close relationship – and I’ve got that. So I learned that from, dad, unfortunately, when he passed away. He died two months after my 18th birthday; it was a real shame, because I just started to feel like I got to know him then.

In terms of your own heart health, is there a benefit to being aware of the genetic risks at play?

Yeah, even my kids too, they’re well aware of what happened there, so they’ve got to be careful what they eat and how they look after themselves, as well. It’s just good to be that way. Dad was in a small country town [Chinchilla, Queensland], and back then they probably weren’t onto it as much. The guys back then might have a pain in the chest, go see the doc, do an ECG and they mightn’t pick it up, so the advice was, “Take it easy”.

I think they’ve learned from back in the 80s, when there was a lot of guys in the country that would drop dead of a heart attack after they’d seen the doctor. It’s happened to a few guys that I know. Things have changed now: any pains in the chest, off you go to the specialist and get a good check-up. I’m sure that, if dad had been checked out properly, he’d probably still be here today. A few of his mates had the same thing; after dad died, they had chest pains, got checked out, had some bypasses, and they’re still here.

Great to hear. Lastly, in 2018 you ran a four-day ‘Music & Movement Escape’ at Byron Bay with your friend and fellow muso Benny Owen; my colleague Trent Dalton attended the event and wrote about it for our magazine. Was that a one-off?

We did one, and people absolutely loved it. It’s very inspirational for anyone that loves music: you get to train with the artists, and at the end, you get an acoustic concert as well. Obviously, Trent’s quite famous now; he wrote the book [Boy Swallows Universe, which became a Netflix TV series], so people know who he is. But at the time, he wasn’t that well-known, and we got him along because we wanted to get a journalist there to write about it.

We’re looking at doing another one again, but we’re just waiting for the right time. It’s a tough time at the moment, financially, for a lot of people. We’ll wait for things to recover and put another one on again. Everyone that I talk to about it thinks it’s an amazing concept and idea. We’ve just got to get it together – but in the next four months, it’s not going to happen for me, because I’m going to be very busy.

Pete Murray’s 56-date solo acoustic tour begins in Darwin (May 9) and ends at Blue Mountains (September 7). Tickets: petemurray.com

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout