Gordi on hotel-room workouts on tour, and choosing music over medicine

The ARIA-nominated artist, also known as Sophie Payten, speaks of parallel careers in music and medicine and staying fit while touring (and how she does it).

Gordi is an ARIA-nominated indie pop singer-songwriter born in Canowindra, NSW, and now based between Los Angeles and Melbourne. Ahead of her third album release, the artist otherwise known as Sophie Payten, 32, talks to The Australian about her parallel careers in music and medicine, exercising in hotel rooms while on tour, and how her experiences working as a doctor during the pandemic influenced her songwriting.

How have you learned to stay fit while touring, Sophie?

I have not always stayed fit while touring; early on, I was more hungover while touring, to be honest. [laughs] Most people who get into the music industry are suddenly surrounded by free alcohol all the time, and it’s kind of hard for any young person to resist. But fortunately, in the last three years or so, I have made better habits. I’m not sponsored by Nike, but I use the Nike Training app, which is free, and has all these workouts you can do in a hotel room. When I’m touring in America, often you’re staying in some motel on the side of a highway; but if we’re touring through Europe, I’ll always go for a run when I wake up in the morning. Or if we’re on a tour bus and I’m arriving at the venue at 3pm, I’ll try to go for a run around the city, because often that’s the only way you’re even seeing the city while on tour. For me, it’s a combination of workouts on free apps, and running with my two feet.

What’s involved in a hotel room workout routine?

It’s basically a lot of body weight exercise. It can sometimes be a combination of yoga and pilates, or it can be HIIT (high-intensity interval training) workouts: lots of planks, lots of mountain-climbers, lots of skiers. This Nike Training app has a number of easy workouts that you can do, and I find that by using your body weight to train, it’s easier to maintain, and I’m less likely to get injured than trying to use weights in a gym. You can really get your heart rate up, and get a good workout in.

Hotel rooms vary in size dramatically; how much space do you need to move?

They do, and often I’m in very small ones [laughs]. I only need probably two [square] metres of space, really. Sometimes I have to do little modifications: when they’re telling you to sprint across the room, I’m doing steps side to side. But often the people instructing are living in some tiny apartment in New York anyway, so it’s relatively comparable.

You’re the first musician in this interview series to mention such a thing. I’m sure it happens fairly regularly, but maybe some people are embarrassed to be talking about it, so I love that you’re so open about it.

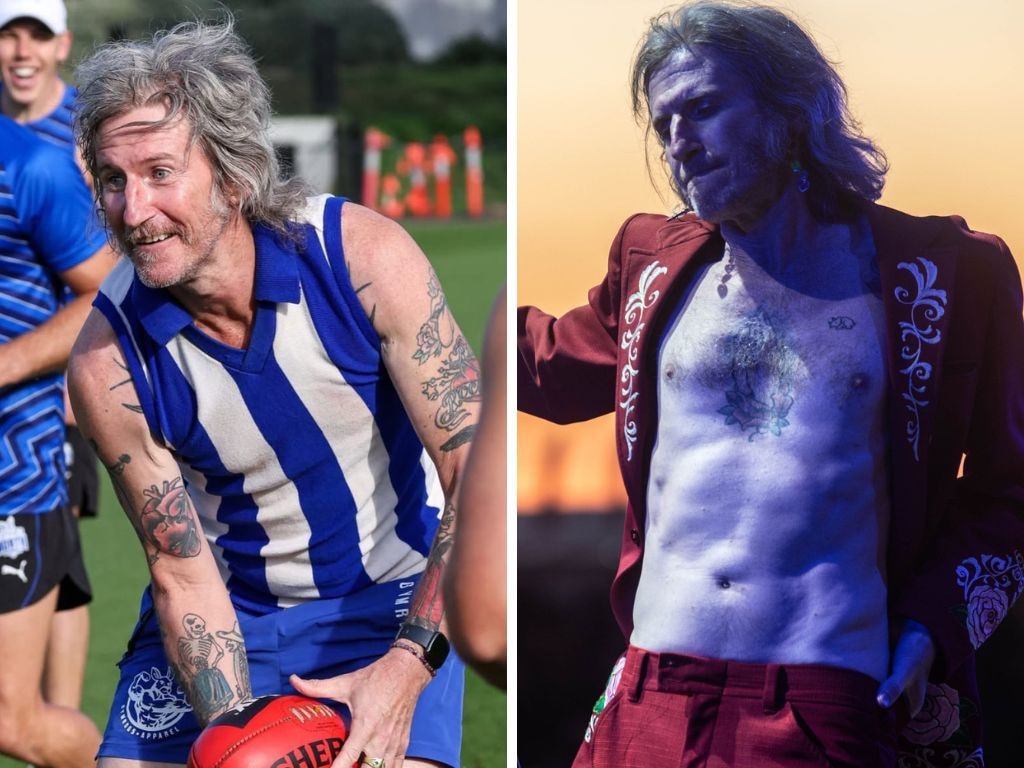

To be honest, up on stage, I’m usually wearing clothing that’s revealing a lot of my body, and so staying in shape is kind of part of my job. As an artist, you think about the kind of image that you want to project to the audience. I like the idea of appearing as a strong, fit woman who’s doing my thing up on stage. Part of achieving that goal is being dedicated to working out six days a week.

It makes sense to me that you want to be feeling the best version of yourself when you’re performing.

It’s all about confidence, right? You can see a performer on stage when they’re confident, and when they’re not. It’s important to me because it’s a big part of my life: I want to enjoy it, and I don’t want to feel self-conscious on stage, and I want to feel confident in my body. It’s become such a critical part of my everyday, and the mental health aspect is just as huge for me.

So those two things are closely linked: if you feel good in your body, you feel good in your mind?

Yeah, absolutely. And touring is a total emotional rollercoaster, I find. It’s something over the years that I’ve gotten more used to, but just even the flow of the day, where you traditionally wake up in some crappy hotel, and you feel so tired from the night before; you’ve probably gone to bed at 2am, and you’re getting up at 7am to do a whole day of driving. Or otherwise, you’ve slept on a tour bus, and you’re trying to conserve your emotional energy all day, so then you can just come out on stage and let it all out. Then you come off stage, and you have this huge high – and then you have to try to go to bed and do it all again the next day [laughs].

Trying to ride those waves can get really exhausting, and I really rely on the endorphins of exercise as a way to give me another burst of good energy during the day that’s separate from the show. I think the actual chemistry inside my head really benefits on tour from having that other moment in the day where I’m getting good energy, and it’s not from other people: it’s just from what I’m doing for myself.

How do you like to spend your downtime; the 22 hours of waiting around before you get to perform?

I mean, it’s funny: you think if you have all day in a bus or a van, you could get a whole lot done. But being on tour, you feel like you’re suspended in this strange world where you really have not a lot of energy to do anything else, because you’re conserving it all for the show that night. And I also get really motion sick in cars and buses [laughs]. So while I would love to be banging out all my “life admin”, I just can’t, really. I listen to a lot of podcasts, and at night, to wind down, I’m usually trying to pick something that’s very easy to watch. Often it’s some kind of nice documentary about mushrooms, or the [TV] series Muster Dogs. I like watching things where I feel like I can put my brain in a hammock, and not have to think too hard.

We’ve spoken previously about your parallel lives in medicine and music. In 2021, you told me that you sometimes worried you were “doing a half-baked job at both, by not giving your full self to either of them”. Have you resolved that since?

Yeah, I guess I probably have, because I’m doing a lot less medicine now. I’ve been doing enough medicine to keep my licence from expiring, but I do feel that my life since the pandemic has ultimately shifted towards doing music full-time – but keeping medicine as a tiny little spinning plate, in case I do want to go back there some day [laughs]. But the pandemic was such a peculiar time where no one could be fully invested in music, because you couldn’t leave the country, or you couldn’t go and play shows like you normally could. I do feel like, at this point in time, I’m more in a phase of my life where music is, thankfully, dominating it – and medicine’s on the backburner, so to speak.

What does that look like in terms of keeping your licence – taking occasional casual shifts as needed?

Exactly. It’s kind of like being a temp in any field. I make sure I get my hours done every year, and it’s always in a different hospital somewhere, usually in Victoria. I’ll drop in and do a few weeks here and there, which is always peculiar to explain to the people I’m working with, because everyone’s always like: “Where have you come from? What term have you been doing?” And I’m like, “Well, I’ve just been doing other, non-medical things…”, and they look at you sideways. I get a little tired of explaining over and over again where I’ve come from, so I’m thinking I might just start making it up [laughs].

Your situation is unique, in that you’re a well-known Australian musician who tours the world, but you also are a doctor. There’s not many of you, Sophie; you might be the only one.

Deniz Tek! He’s another one. Actually, there’s two: [Radio Birdman songwriter and guitarist] Deniz Tek, and Alex Cameron, from [Adelaide rock band] Bad//Dreems, he’s a plastic surgeon. In my wide search, they are the two people I have found who do a similar thing – although they are further along in their medical fields than me.

You don’t strike me as the kind of person who likes to go around crowing about your achievements and saying: “Look at me. I’m also a well-known musician!”

[laughs] Well, I try to keep it relatively under wraps. I was working during the pandemic and this friend of mine, who was another fellow resident, finally found out when I went out to do this press thing in the morning; it was one of Michael Gudinski’s initiatives of getting music back in front of people. I said to her, “Could you cover for me for an hour? I’ll do some discharge summaries for you, or something”. She worked out what was going on: there was a piece in a newspaper that came out about me – it might have even been one you’d written, I’m not sure – but she cut it out, laminated it and stuck up copies around the wards [laughs].

That was honestly my worst nightmare, so I do try to keep it under wraps as best I can. But coming out of the pandemic, I needed some space from being in the hospital, because it was a pretty torrid time. I took some time away, and went and wrote a record, which I now am glad I can share with the world in these coming months.

There’s a couple of songs on your new album, Like Plasticine, that are centred in a hospital setting. How did they come to life?

Yeah, there’s two songs that I wrote about the same experience in the hospital: PVC Divide, featuring Anais Mitchell, and the closing track, which is called Automatic. For a solid 18 months – from the start of the pandemic until the middle of it – I really struggled to write anything, because I was feeling like I was faced every day with other people’s grief and tragedy on a scale that I hadn’t fully experienced before. In the context of the global tragedy, I found it challenging to try to write from my own perspective, because it didn’t feel right to me at the time. Obviously, there’s always grief in the hospital; that’s part of the everyday, and you do get a little desensitised to it, to be honest. But every now and then, there’s something that happens – some patient or some case – which really stays with you.

I wrote these two songs about one of those particular moments where I’d been working on a post-operative rehab ward, and I had befriended this patient. He was a lovely man; he used to call me Sophia, even though that’s not really my name, but I didn’t mind. He had been recovering from brain cancer; he’d had an operation to remove a tumour, and he was supposed to be working towards discharge. We did a progress scan, just to make sure it was all OK; it showed that the cancer had grown back at an unprecedented, aggressive rate. It was inoperable, and he was basically now going to be put on a palliative pathway.

I had to go in and tell him, and usually when you tell a patient devastating news, they have their family there with them, and your job – as the healthcare worker – is that you go in, you deliver the news in the most respectful, sensitive way, and then you leave the room and you let them come to terms with that, with their family. But the pandemic meant that no one could have visitors, so these kinds of events had to happen in a silo. So as a medical practitioner, you had to play all these roles: you had to be the practitioner giving the news, and then you had to be the support system as well, in a way that was abnormal.

This man and I had just developed such a nice little friendship. I went in, and he could see on my face immediately that it was not good news. I was trying my best to hold it together, because it wasn’t my place to be the person who was upset. I told him, and he was a religious man, and he said, “This is what was written for me”. We had this very devastating moment together – and then I went and sat in my car, and cried for a while.

Devastating things happen all the time in hospitals; that’s part and parcel of the job. But it just felt all the more confronting for having to play all of these roles that you don’t normally have to. I couldn’t write about that stuff for a while, because it made me so sad. But then, a little while later, I locked myself away for a week to try to write, finally – and those songs kind of just poured out.

Thank you for sharing that. The first lyric in PVC Divide is so brutal: “She said that she watched him die on FaceTime / It all took about three days.”

Yeah, that began as a song about my experience, but then, that didn’t also feel right, because it was an experience that so many people were having. I’d read a plethora of devastating articles on people’’ experiences of losing loved ones during Covid. That first line I had read in an article, and that to me really echoed how I had felt about having to deliver this news to this man – and then he had to FaceTime his family and tell them. There was this impenetrable rule between people that really made that time so traumatic, so I ended up weaving in a bunch of stories that I’d read, with my own.

As a songwriter, is there a part of you that’s grateful for having had these experiences, which you can then draw on in your art?

Yeah, look, in a way, I’m always able to write more when I’m living more. And I think that the further into my songwriting career I get, the more attention I’m paying to other people’s stories. The pandemic was fertile ground for everybody having a story that was worth telling, but it was just trying to figure out: “Should I be telling other people’s stories? Should I be looking at their stories through my own personal lens? Is that selfish? Should I be someone who’s trying to write about this experience that’s brought the world to its knees?” It was posing a lot of existential questions to me, as a songwriter, the main one being: Who am I to comment on this stuff?

But then, in a strange way – as we’ve mentioned earlier – there’s not a lot of medical people who are songwriters as well. In a way, I felt really well placed to make a comment on all of this, using the medium that I know best.

We spoke earlier about the prevalence of alcohol in the music industry. Given your medical knowledge, are you smart enough to avoid things like that, or are you just as dumb as the rest of us?

[laughs] I’m maybe somewhere in the middle. I’m not a sober person, but I have found, with each year that passes, that when I drink, I cannot sleep. So I drink when I have good reason to – but otherwise, I abstain.

Gordi’s third album, Like Plasticine, will be released in August via Mushroom Music.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout