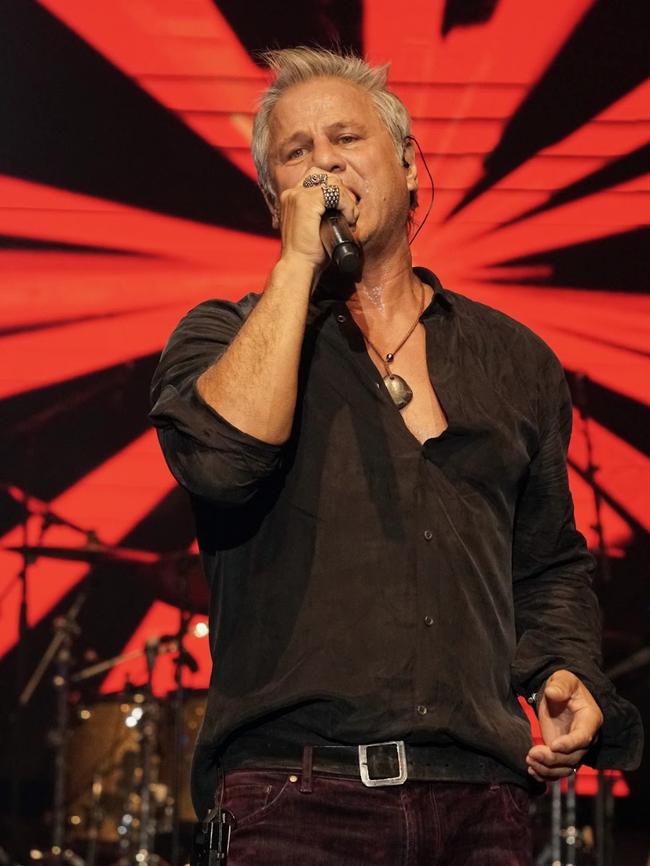

Jon Stevens on health, wellbeing and the terrifying heart scare that saved his life

The rock singer reveals how he balances his physical and mental health while touring, how following doctors’ advice saved his life in 2009, and why he finds inspiration in The Rolling Stones.

Jon Stevens, 63, is a New Zealand-born singer best known as the frontman for Australian rock bands Noiseworks and INXS (2000-2003), as well as performing as a solo artist. In early January, he spoke with The Australian about balancing his physical and mental health while on tour, how following doctors’ advice saved his life in 2009, and why he continues to be inspired by The Rolling Stones.

What have you learned about staying fit while touring today?

Well, there’s regular fitness, and there’s gig fitness. Gig fitness comes about when you’re constantly on the road, and you have tunnel vision: you’ve got to try and get your energy to show up at the right time, every night. We’re always having late nights; it’s always hard to come down after a gig. On the road, I usually don’t get to bed ‘til 1am or 2am; we might have a flight at 8am or 9am, and I might sleep on the plane. You get to the hotel, dump your stuff and go and eat. If you’re on stage around 8pm, I like to eat around 2pm or 3pm, and that’s my main meal until after the show. The days of eating an hour or two before the gig, where you go on stage and you’re as full as a bull … [laughs] After 45 years of touring, I just have a way of doing things that are pretty routine, mentally, more than anything.

Earlier in your career, was managing your fitness more a case of trial and error?

It was “drink ‘til you drop”, rock ‘n’ roll excess. It was fun, and you’re young; certainly back in the 80s of Australian pub rock, it was ferocious out there. The energy was young people going crazy and sweating; there were many, many gigs around Australia where they’d cram 1000 or 2000 people in like sardines, and it would rain inside [the venue] from the condensation. It was a sight to behold; nowadays, with perfect airconditioning, it’s a bit different. I hate having airconditioning on stage, because there’s nothing worse than being hot and starting to sweat – and then being cooled down at the same time, by cold air blowing on you. That’s a recipe for disaster, and I got sick many times from that – to the point where I figured out what it was, and said, “I can’t do that – we’ve got to stay hot the whole time”.

It was pretty wild back then, obviously, compared to now, where I’m a father and grandfather. I’ve got three grandchildren – aged 13, 10 and two – and the whole idea is to stay alive as long as you can, especially after all these years of touring. The thing is – I love performing. I love touring. I love travelling. I love airplanes. [laughs] I grew up in a very small town in New Zealand, and I can just remember wanting to get out and see the world. I came to Australia, I went to America, and then I had a choice to come back to Australia or New Zealand. I said, “You know what? I’m coming back to Australia. It’s a lot warmer.” [laughs] That was January 1981 – a long time ago.

What have you learned about taking care of your voice?

Don’t smoke too much; I don’t smoke anymore, but when I was young, everybody smoked. But taking care of my voice? Don’t worry about it. I learned a very valuable lesson in Queensland. We were on tour with Noiseworks in about 1986, and I had full-blown bronchitis, pneumonia – you name it, I couldn’t talk. But we were on the road and had to do the gig. I sat in my hotel room just freaking out, but telling myself, “We’ve got to do it. Can’t get out of it. We’re here. Gotta do it.” I got on stage, sang fine – then got off stage and couldn’t talk. I learned a real valuable lesson, that most of it was mental. I didn’t hit the notes perfectly, and I was a bit scratchy – but I did it under that much duress, that I realised it was purely mental [strength] that got me over that hump.

From that day on, I never worried about my voice, regardless of how long I’d stayed up for. [laughs] I always knew that, if I was focused mentally, it would be there, you know? And the way I sing, I’m not a crooner; I’m going for it. I guess it’s just that energy that you have to pull out of yourself to get to that point of delivery. It’s a full-on mental thing; a lot of nights you don’t have that energy, but that’s called controlling your adrenaline.

In terms of exercise, what are you fond of?

I go to the local gym and push some weight around. Obviously I’m drawing in big breaths [when singing], so cardio is a big one. But it’s funny: I’m 64 this year, and August [2023] was the first time I stopped going to the gym. We were on tour so much, and I’d go to the gym in the morning and do some sort of session, then do the gig [at night] – but it got to the point where I physically couldn’t do both. I’ve been training all my life, really; I’ve always been a physical person. But I had to make a choice: stop bashing yourself in the morning at the gym, because my body wasn’t holding it as well to the gigs. At my age now, I’ve found that I can’t do both properly.

So I haven’t been to the gym in a year and a half, but I intend to get back. We finish this tour in March, and I’m going to take a lot of time off, and just focus on that. I’m as hard at training as I am at singing: if I’m doing it, I’m doing it all-in. Right now, I’ve actually got this thing on. [He opens his shirt to reveal a sensor stuck to his chest, which feeds data to a phone app.]

My heart’s being monitored every day. I got back on Friday from overseas, I talked to my cardiologist and he said, “We’ll put this on you”, because we’ve been playing when it was 38 degrees on stage, and I don’t want to have another incident. It’s being proactive, as far as being aware that I’m not young. I am fit, but my main left artery – which they call “the widow maker” – is fully blocked, and that happened after I had my fourth Covid jab in September 2022.

I got a real bad chest pain during a gig; managed to finish the gig, went home, was tight in the chest. Went straight to the hospital and said, “Something’s going on.” They did an angiogram on me, and I’d had my double heart bypass in 2009, so I’d been fine from then right up to 2022. They put a stent in me, and they put me on new drugs; I have to inject myself with this stuff called Repatha, and up my statins, and all this stuff. My main left artery was one of the original grafts, which I get checked regularly, and when I had it checked in February, it was 100 per cent clear. But by September it was blocked, and that’s why I had the chest pain, and it was about to blow. They put the stent in, and it seems to be working: I’m still alive.

How did you end up on the operating table to undergo open heart surgery in 2009?

I went for check-ups. In fact, I had never been checked up properly ever before in my life and my GP, God bless her … I’m the youngest of 11 children, and heart disease is rife through my whole family, and through both sides of my parents’ families. I was 47 years old at the time, and she wanted me to get all these tests. I went to the cardiologist, Dr Freeman, went on the treadmill, and passed every test with flying colours.

But the cardiologist at the end said, ‘Hey, listen, everything’s looking really good, but there’s a thing called an MRI – I think I want you go and do that next week.’ The scan cost $600, even with full medical insurance; it was an afterthought on the cardiologist’s part. I was living in Sydney at the time, and the following week I went into the Bondi Junction pathology place. They did an MRI, and put the dye through me; I got up, got in my car, drove to Bondi Beach – and then I got a phone call.

Dr Freeman said, ‘Jon, what are you doing?’ I said I was about to go for a swim, then get something to eat – it was a beautiful blue sky day. He said, ‘Get in your car and get to Prince of Wales Emergency now. Don’t go home. Don’t stop and talk to anyone – and whatever you do, don’t exert yourself.’

I did what I was told: I drove to [the hospital], they sat me down in a wheelchair when I came in, and they said, “We’ve got you now.” I said, “What’s going on? Am I going to have a heart attack?” They said, “No – you’re about to drop dead. Your main left artery is fully blocked. It’s Thursday; you’re not going to last the weekend. It’s going to blow.”

It’s just wild. I was living in Bronte Beach, and I used to run to Bondi and back, or run to Coogee and back, and go to the gym for an hour – which I’d done that day, too, the day I got the MRI scan. [laughs] I was fit as a Mallee bull, but you can’t see what’s going on inside. It’s all genetics.

I said, “Man, I’ve had a good time over the years in rock ‘n’ roll, Doc …” He goes, “You could have been eating lettuce and drinking water all your life – it would not make any difference to what’s going on. You have a predisposition to blocked arteries; it’s as simple as that. Times have changed now – but we’ve got you.” I was in hospital for a month.

That’s an extraordinary story, Jon, thank you for sharing. What did you learn from that experience that you carry with you today?

I’m very, very lucky, and very grateful. My time is not done. I distinctly remember lying in hospital going, “I’m not going to meet my grandchildren.” I didn’t have any grandchildren at that point! [laughs] But I just really wanted to meet them; I really wanted to live. And also, just the fact that I felt lucky. I was elated because I was blessed that I found out in that fashion; I didn’t have a heart attack. Something bad didn’t happen. It was actually the warning.

It was just weird. I put it solely down to my GP, actually, because I was fit and healthy, didn’t really care about anything much [health-wise] – and she basically got my calendar, picked the day, and said, “You’re going to see this cardiologist on this day.” It was her – Dr Andronicus. Amazing.

As a generalisation, men are not great at reporting their own health issues or listening to medical advice. My favourite part of your story is that you listened to the advice, and followed through. What do you want to say to blokes in particular when it comes to matters of health?

I’ve been saying that since way back then: get checked up. You check your car; it’s pretty basic stuff. But men, we’re proud – or stupid. [laughs] I don’t know. But your health is your wealth; that’s a very true saying. I always say, “Listen, if you’ve got kids, or you’ve got grandkids – you owe it to them to be around as long as you can.”

Well put. Lastly, on the mental health side of things – how do you stay mentally fit while on tour?

Mental health is such a massive problem in the world today. I mean, I’ve lost brothers to suicide. What I went through, and what I still have to deal with – that’s physical and genetic. But mentally, it’s tough for people. You’ve just got to focus your energies on being a bit more positive. As the singer, if I fall over, everybody falls over. You’re travelling with 10, 15, 20 people – or if you’re on the big tours, there’s a lot more. There’s a massive responsibility as the singer that guitar players don’t have; that’s why you’ve got Keith Richards and Mick Jagger, you know what I mean? [laughs]

I saw The Rolling Stones last year in Los Angeles, and honestly, they were such an inspiration. I’ve always loved them anyway, but it was amazing, Mick running around like that [at age 81], and Keith and Ronnie [Wood] still just doing their thing. I was shaking my head, going, “I want to be that when I grow up.” I take my hat off to them, and to AC/DC; those guys are still running around, playing to 100,000 people every night. It’s mind-boggling, and that’s the power of music: the world would be a very dull place without real, live music.

Jon Stevens’ upcoming concerts include Noiseworks’ Take Me Back tour (February 2, 7 and 21), as well as a solo appearance headlining Summer Fun Fest (February 16, Yarra Valley) and supporting Roxette at A Day on the Green (March 5, 15 and 16). Tickets: jonstevens.com

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout