What went wrong and what did we learn from the pandemic?

What the Covid-19 pandemic has taught us as we look to the future.

From pandemic preparedness, financial support, mixed messaging, lockdown overreach and keeping children out of schools, here’s what the Covid-19 pandemic has taught us as we look to the future.

Trust: abuse it and lose it

Remember when we were all in this together? When national cabinet provided a sense of collective decision-making, a triumph of policy over politics? This was 2020 during the early crisis phase of the pandemic when trust in government peaked.

It didn’t last. By late 2021, in the wake of the Delta wave and as lockdown fatigue set in, the Australian Leadership Index found most people didn’t believe government was committed to the public interest or served the public good. Faith in other institutions shifted too, as rushed and heavy-handed tactics introduced amid a sea of mixed messaging dented public confidence.

Fault Lines, an independent review into Australia’s Covid response led by former Western Sydney University chancellor and top public servant Peter Shergold, found that many Australians felt they were being protected by being policed.

“There were too many instances in which government regulations and their enforcement went beyond what was required to control the spread of the virus, even when based on the information available at the time,” the review said.

This sort of overreach, the authors said, undermined public trust and confidence in the very institutions that were vital to the crisis response.

A federal Senate committee tasked with scrutinising the government’s response to Covid-19 found national cabinet was “ineffective” in delivering the level of national unity required during the crisis.

An expert health review, Key Lessons from the Covid-19 Public Health Response in Australia, concluded public-health measures that disproportionately affected some communities led to mistrust in government.

“Timely, clear and open communication, combined with decision-making that is evidence-informed and as consultative as possible, is essential to maintain population co-operation and trust,” the review said.

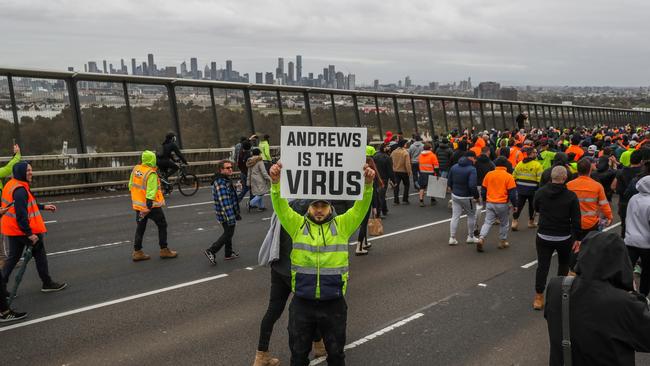

The rise of extremism

As public trust dissolved, a new crack opened to people holding more extremist views, according to Griffith University professor of criminology Kristina Murphy.

“We also observed a rise in people believing in conspiracy theories that undermined public health responses to the pandemic, and a concerning phenomenon of libertarians, anti-vaxxers, populist far-right groups, sovereign-citizen groups and conspiracy theorists congregating at anti-lockdown protests across the country and sometimes engaging in violent protest,” she wrote.

ASIO Director-General Mike Burgess warned last year that extremism linked to rage over Covid mandates and lockdowns had settled but still existed.

Not all protesters, however, were extremists. “Evidence suggests that participants were there for a variety of reasons, often because of a sense of deep despair and alienation intensified by the response to the pandemic,” political experts Tom Chodor and Shahar Hameiri concluded in their book, The Locked-up Country: Learning the Lessons from Australia’s Covid-19 Response.

Plan and prepare

Australia was unprepared for the Covid pandemic. Numerous reviews found plans were not regularly updated or rigorously tested, medical stockpiles were depleted, surge capacity planning was inadequate and vulnerable supply chains exposed.

“Inadequate planning meant that too many decisions during Covid-19 had to be made on the run and with limited evidence and little consideration for complex trade-offs between health, social and economic outcomes,” the Fault Lines review found.

The expert health review found “existing preparedness plans were insufficient and major system weaknesses were exposed in the Australian residential aged-care sector”.

The Senate committee pointed to an Australian National Audit Office report that found not only was the government’s pre-pandemic planning deficient, but departmental officials were aware of these deficiencies and failed to communicate them to ministers.

A review into vaccine procurement by former Department of Health secretary Jane Halton also found pre-pandemic structures and processes were not fit for purpose in an emergency context.

There is broad support for the federal government’s planned Australian Centre for Disease Control, an independent entity charged with ensuring pandemic preparedness, gathering national data and protecting the country in a national health emergency.

“In the absence of a CDC-like entity, Australia lacks a mechanism to proactively collate, analyse and monitor disease surveillance data at a national level,” the expert health review found.

What about the kids?

The long-term effects on school-age children are still being calculated but there is growing concern at school refusal rates, behavioural problems, knowledge gaps and disengagement from formal education.

The Australian Secondary Principals’ Association has warned of a rise in behavioural problems along with screen and gaming addictions and gaps in numeracy and literacy knowledge.

‘It was wrong to close entire school systems, particularly once new information indicated that schools were not high-transmission environments’

Children’s charity Save the Children described it as a generational rupture.

“The pandemic has disrupted children’s learning, weakened their connection to schools, placed severe pressure on their mental health and wellbeing, and significantly increased disengagement,” it told a Senate inquiry.

The expert health review acknowledged the interests of children and young people were at times compromised, while the Fault Lines review concluded the costs of educational disruption and increased mental stress will continue for years.

“It was sensible to close schools where there was an outbreak and when little was known about how the virus spread. But it was wrong to close entire school systems, particularly once new information indicated that schools were not high-transmission environments.”

Secrecy and censorship

Who was making crucial decisions and on what basis? Lack of transparency around decision-making, and outright dismissal of people who questioned “the science”, created confusion and damaged public trust.

“Scientific opinion was in fact more divided on many Covid-19 measures than many admitted or were led to believe,” the authors of The Locked up Country said.

“Governments’ public health policies were often based on flimsy evidence, and indeed kept changing throughout the pandemic, often quite radically.”

The Fault Lines review noted: “We were told to follow the health advice at all costs, but the health advice being received by governments was not always provided in a transparent manner.”

Non-disclosure agreements on data, modelling and advice prevented scrutiny, the review found. “A lack of transparency saw a plethora of external health experts become media celebrities, filling the information gap in ways that sometimes created confusion and undermined health advice.”

People who openly questioned the effectiveness of lockdowns, mask mandates or vaccines were dismissed as conspiracy theorists, and social media posts were censored.

Doctors risked regulatory action if they said anything that could be seen to undermine the national vaccination program.

The (Labor-led) Senate committee report urged greater transparency, saying the public should have been provided with the health advice that informed government decisions on issues such as community safety, livelihoods and personal freedom.

Government spending

Financial support for workers and businesses was a necessary response to forced lockdowns, but was it too generous? Numerous experts have pointed to government stimulus and low interest rates contributing to higher inflation.

Modelling by respected economist and Australian National University visiting fellow Chris Murphy found for every $1 of income the private sector lost, fiscal policy provided $2 of compensation. The effects of this overcompensation and loose monetary policy, he said, generated excess demand that temporarily added up to three percentage points to the annual inflation rate.

“The primary lesson for future pandemics is that fiscal policy should compensate, but not overcompensate, for income losses.”

The Fault Lines review found governments and the Reserve Bank of Australia understandably over-insured.

“Their judgment was that it was better to do too much than too little, particularly when faced with extreme uncertainty. But we are now living with some of the costs of that over-insurance as inflation and interest rates rise sharply.”

Who’s in charge?

Was it the politicians or the chief health officers? The Fault Lines review found public health officials, including chief health officers, were given disproportionately greater decision-making authority.

“Clearly we need more checks and balances in our system, especially when it comes to the power of health ministers and CHOs to impose draconian restrictions without reference to parliaments or even cabinets. We cannot face the next pandemic with the same unfettered powers.”

The federal Senate committee recommended clearer delineation of commonwealth, state and territory responsibilities while the Halton review agreed the role of decision-makers and advisers should be clarified.

The Royal Commission into Aged Care received many submissions that identified confused and inconsistent messaging from providers and different levels of government: “All too often, providers, people receiving care and their families, and health workers did not have an answer to the critical question: Who is in charge? At a time of crisis, such as this pandemic, clear leadership, direction and lines of communication are essential.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout