Working Class Man: Jimmy Barnes’s second memoir

Rocker Jimmy Barnes’s stark memoirs are the ultimate compliment to writing.

Last year Jimmy Barnes published Working Class Boy, the opening instalment of a memoir that proved too long, and too thorny, to be contained in a single volume. That first book, which broke off just as Barnes was joining a nascent Adelaide band called Cold Chisel, was astonishing in several ways. It told the story of a childhood that seemed to have been ripped from the most baroquely grim Dickens novel and transplanted to the suburbs of 1960s Australia. And it found a starkly effective language in which to tell that story: a stripped-back prose, full of jagged stops and starts.

Is Barnes’s second volume of memoirs as good as the first? Well, it’s certainly less hair-raising. Then again, it could hardly fail to be. In that first volume, Barnes had the element of surprise going for him. None of us knew what his childhood had been like. And we had no right or reason to expect the arse-kicking rocker would suddenly turn out, at 60, to be a first-rate writer. He didn’t just describe hunger and cold and violence; he made you feel them.

This time we are in more conventional territory. We know the basic story: the journeys from gig to gig in the unreliable van; the horrible pubs; the towns that blur into one another; the clueless record executives; then the drugs, the groupies … Barnes’s material is no longer unique. It’s the fare of many a rock memoir. There is a limit to how new such stuff can be made to sound.

Does this mean we’re dealing with a lesser book? The answer is yes, if we decide to detach this book from the first one and treat it as a wholly separate thing. But I think it’s a mistake to do that. This book is a sequel in the fullest sense of the word. Its roots strike deep into the soil of that first book; you can’t pull them out without ruining a careful act of cultivation.

Barnes has said that he needed to get the story of his childhood off his chest before he could write the story of his career. As readers, we would be wise to take his hint and treat a reading of the first book as a prerequisite for a full understanding of the second.

Of course you are free to read this book without having read its precursor. But you’ll be getting a story that is all action and no subtext. Barnes spends a lot of this book running away from his past. If you don’t know about the gothic nightmares he’s running from, his behaviour may strike you as meaningless. And meaning is precisely what Barnes has used these books to go in search of. He wants to make sense of his life — for his readers, but first of all for himself.

Viewed from the outside, the story described in this book is glorious. Cold Chisel sweats its way from obscurity to fame. Along the way Barnes meets and marries the endlessly patient Jane, with whom he raises an exemplary family. Chisel disbands on its own terms, at the peak of its form. Barnes achieves raging success as a solo artist, racking up sales that far outstrip those of his former band. Then Chisel reforms, triumphantly.

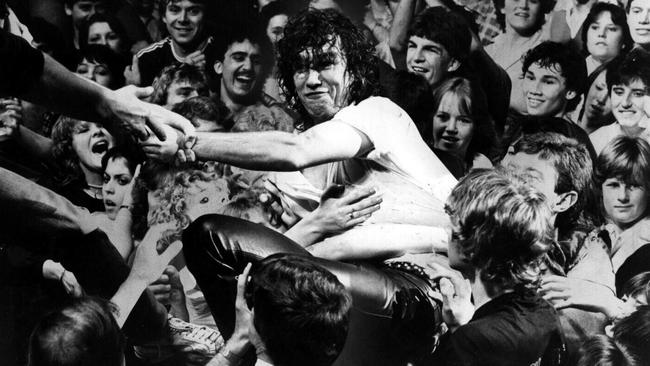

These days Jimmy would seem to have it all. He’s fit, he’s genial, he’s the great-grandfather who can still pull on a pair of leather trousers and emit an air of genuine menace on stage. But memoirs look at such things from the inside; and from that angle, Barnes’s career has been a ragged ECG of shocks and disappointments.

Cold Chisel, apparently, saw amazingly little of the money generated by its records and tours. Even after many years at the top, Barnes could hardly afford to rent a house, let alone buy one. His solo success wound up presenting him with the opposite problem: when interest rates kissed the sky during the 1990s, Barnes was so overcapitalised that he had to sell his family home.

Barnes’s financial profligacy was not unrelated to his intake of booze, mainly vodka, and drugs, chiefly speed and cocaine. His appetite for these things was prodigious and nearly proved lethal. Here again it pays to have read the other book first.

Read this one by itself and you will find yourself looking at a cliche: the self-destructive rock star. But the first book lets you know, in pitiless detail, exactly what the self-destroyer was out to destroy. In this respect and others, the first book shines a light into the second. The adult who behaved like a child is explained, in large part, by the child who had to behave like an adult.

Barnes does not spend much time rehashing the specifics of his childhood here. Why would he? It took him a whole book to tell the story the first time. Moreover, he hints that the exercise was so painful that he has no desire to repeat it. But if he declines to revisit his childhood in detail, he does write eloquently about its unshakeable and corrosive influence. The spectre of those years has never left him; it has made even his richest successes taste sour.

I was convinced it wouldn’t last. I’d end up back in the gutter where I belonged … For years that’s what I was expecting, and when it didn’t happen, I did my best to make it happen. That’s where I belonged, in the gutter like the rest of my kind. The disease was still lingering in me. It was strong. I drank. I drank way too much. I could feel the shame even when I had nothing to be ashamed of.

In this passage and others like it, Barnes evokes the lasting effects of a deprived childhood as convincingly as I have ever seen them evoked. But arguably it takes someone as successful as he is to alert us to the sheer incurability of the “disease”. After all, here is a man who seemed to achieve everything. And he’s telling us that everything still felt like nothing, given the childhood he had to carry around. If even Barnes feels that way, imagine how less celebrated survivors of such upbringings must feel.

Here again Barnes shines light into a familiar trope: the figure of the rocker with a limited sense of self-worth. He puts life and meaning back into the cliche. At his best, he does that at the level of the sentence too. When he hears himself using a stale figure of speech, he will frequently give it a revitalising tweak. Mentioning his desire to get out of a certain promoter’s hair, he adds: “He had a lot of hair to get out of, now that I think about it.” Or in reference to a less likeable fellow: “I bit my lip instead of punching his.”

There’s also a hint, in this second quote, of one of Barnes’s less laudable habits. He has an occasional tendency to minimise, or joke about, things that he has elsewhere demonstrated to be no laughing matter. His first book described, in remorselessly vivid terms, what getting punched in the face really looks like and feels like. So when he seems to speak lightly of violence it comes as a surprise, as if he’s betraying his better self.

Similarly, one of the more memorable things about the first book was the thoroughness with which Barnes evoked the squalor and destructiveness of drunken behaviour, particularly his father’s. That book seemed determined to bury, for all time, the notion that intoxication is somehow roguish or charming.

Yet late in this book Barnes inserts a scene that comes perilously close to reviving that myth. He depicts himself drunk and coked-up aboard a trans-Pacific aeroplane during the dying days of his insobriety. While “terrorising” the other occupants of first class, he snaps a seat and lands on the feet of the woman behind him, who “just laughed and shook her head in disbelief”. “Thank God the crew liked me,” he says. Maybe they did; or maybe they were too scared to say what they really thought.

But it would be churlish to dwell on Barnes’s occasional attempts to have these things both ways. Indeed, you could argue that such inconsistencies are a by-product of the fearlessness and honesty with which he has applied himself to his general task.

These two books are an exercise in self-excavation; what they present us with is not a perfectly polished work but something more like a raw and slightly unstable cross-section of the earth, in which multiple Barnes selves stand roughly stacked like archeological layers.

Barnes the angry rocker sits on top of Barnes the helpless child; Barnes the retrospective self-analyst sits on top of both. And speckled through all these layers are contributions from Barnes the nervous jokester. Yes, these figures sometimes contradict one another or step on one another’s toes. But the uneasiness of their coexistence is a mark of the project’s craggy authenticity.

Authenticity is not a concept one normally associates with celebrity memoirs, of course. But this isn’t a celebrity memoir. It’s a serious autobiography that happens to have been written by a celebrity. The distinction is fundamental. It isn’t just that Barnes can write. It’s that he wants to. Most celebrity authors don’t even have the desire to examine themselves critically, let alone the skill. They treat books as just another product to get their face on. The stuff inside is an afterthought.

Barnes, on the other hand, has paid writing the ultimate compliment. After 60 years on the planet, he wanted to arrive at a full understanding of himself. And he felt that the best instrument with which to do that was writing. By which I mean real writing: writing as a process, a way of finding things out. The results are a victory, not just for Barnes but for the written word itself. We need all the reminders we can get, these days, that there are still some things that only books can do.

David Free is a writer and critic. His new novel is Get Poor Slow.

Working Class Man

By Jimmy Barnes

HarperCollins, 512pp, $49.99 (HB)