Picture this: an amateur’s labour of love for old Brisbane

Imperfect as Australia is, there is no better country in the world to live in. If young people have been told otherwise, their teachers have misled them.

When Marcel Proust was trying to characterise the nature of the involuntary memory famously provoked by tasting a madeleine cake dipped in linden tea (tilleul in French) and suddenly reliving the whole world of his childhood, he contrasted this experience with leafing through an album of family photos, which preserve only the empty shadows of past times.

Certainly the overwhelming impression of family photo albums is one of melancholy, for every picture is of a time that has now vanished, of happy occasions now past, of people now departed. When collections of unidentified family photographs from remoter years are discovered, the feeling is less personally poignant but the sense of transience even greater. Who are these ladies and gentlemen dressed for a formal occasion? Who are these children riding ponies in the country? Whose funeral are these mourners attending?

But how many people collect pictures these days? Albums belonged to a time when photographs were physical objects that had to be developed and printed in specialist shops. There was a cost involved, and the inconvenience of taking the film to the shop and collecting the packet of prints. We value things that cost money and take trouble; photographs today have lost that unique object value entirely.

The cost and trouble also meant photographs were less promiscuously taken; the camera was brought out for special occasions: that’s why we have so many photographs of weddings, christenings and funerals, of birthday parties and family Christmases and overseas trips. We still instinctively take photographs at important events that mark an epoch in the history of a family, like weddings and funerals; and there are now businesses that will turn your travel pictures into a book, to immortalise your memories.

All of that was changed by the advent of digital photography, but especially by the appearance of the smartphone almost 20 years ago. Just as social media only really took off once it became accessible on a handheld device – turning the whole world into screen addicts within only a year or two – so digital photography was supercharged by being always available at the touch of a button, without any need to consider aperture, focus or any of the other technical things we had to understand to use an analogue camera. The combination of instantly accessible photography with instant digital transmission via email or posting to websites in turn made social media immeasurably more seductive.

Those who have grown up in this new world have thus been shaped by an entirely different economy of the image. They don’t have albums, or at least physical ones, although smartphones organise their pictures into periods and themes, and they are conveniently all date-stamped. All of us have been to a greater or lesser extent drawn into this world. But like all advances in technology today, it ultimately increases the divide between the intellectual and cultural haves and have-nots. For one group, it can be a useful tool; for the other, it is another source of distraction, dissolving experience into a kaleidoscope of Instagram selfies, a flow of transience without a pause for melancholy or self-awareness.

As it happens, a very old photographic collection discovered in Brisbane is testimony to how much can be recovered from such records with careful research.

In 1983, hundreds of glass plate negatives was found by chance under a house in Red Hill. The glass negatives were stored in cigar boxes and for the first 30 years were thought to number 300; then in 2014 a further box of 92 plates turned up the Museum of Brisbane’s storage facility, considerably adding to the size of the archive.

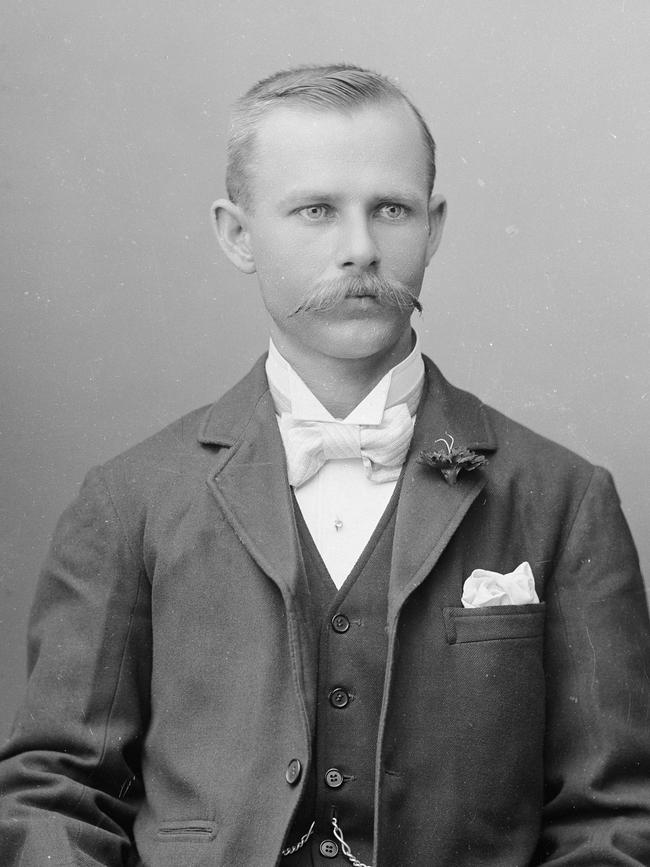

They are the work of an amateur photographer, Alfred Elliott (1870-1954) and document the history of Brisbane from about 1890 to 1940.

Alfred was born in Devon in January 1870, and came to Australia with his parents when he was five although the ship was held up by a period of quarantine after a typhoid outbreak on board and they did not disembark in Brisbane until February 1876. His father became headmaster of the school that Alfred attended, but he died in 1882 and little is known about how the family managed in subsequent years.

Alfred grew up to become a bank clerk and married a girl from a family that may have been somewhat grander than his own; at any rate he seems to have done quite well in his subsequent career and the archive includes photographs of the family – they had two children – and of their handsome residence called Tibrogargan in Stanley Terrace, Taringa.

Elliott was a relatively early adopter of the new technology of photography, which had only been really available since the 1840s and still required considerable skill and expertise, both in taking the pictures in the first place and, of course, in developing and enlarging them.

We also have to remember that until the invention of the electric enlarger in the early 20th century, negatives were generally printed as contact prints using the light of the sun, so that early images were the same size as the original glass plate.

The exhibition includes Elliott’s camera and boxes in which the negatives were found, to give a more concrete sense of what was involved in taking these pictures – so different from the unthinking ease with which, as already mentioned, everyone takes snaps on their phones today. Elliott was in fact, though an amateur, an able technician and serious about his practice; the exhibition even includes slide rules that he devised himself to calculate exposure times, as well as, we are told, developer solutions and temperatures.

It is a measure of how unfamiliar the whole analogue process has become today, especially for young people – unless they have been lucky enough to attend a school that still maintains a traditional darkroom – that the exhibition curators feel it necessary to explain the very idea of a negative. Several are thus displayed with a wall text explaining that the camera produces a negative image which has to be reversed into a positive in the printing process. There is for example a negative of his picture of a sailing boat on the Brisbane River (1896), as well as some others, which appear later in the exhibition in their positive form.

Elliott’s main interest was in the growth of Brisbane, and the period of his documentation corresponded to its transition from a small colonial outpost to an increasingly important urban centre (its population tripled between 1890 and 1940), especially after Federation in 1901. He was proud of the progress of his city and he loved to photograph important civic structures like Old Government House which had been built in 1862 and by 1908, when he took the picture in the exhibition, was about to be transferred to the University of Brisbane.

His desire to celebrate the development of his city and its society perhaps explains his fondness for stereoscopic photography, which already had a long history dating from the middle of the 19th century, because it was particularly associated with the picturing of famous monuments and natural beauty spots. Stereoscopic photos were taken with a special double camera that exposed two plates through twin lenses, reproducing the slightly offset views that we have in binocular vision. The resulting pair of photographs must be looked at through a stereoscopic viewer – included in the exhibition – so that each of our eyes sees the slightly different image and they are combined in the visual cortex to produce the illusion of three dimensions.

Among the subjects Elliott chose for his stereoscopic photographs was the new Victoria Bridge (1908), completed in 1897, replacing two earlier bridges that had collapsed or been destroyed by floods. The stereoscopic view thus invites us to wonder at a triumph of modern engineering. But other stereoscopic views illustrate different aspects of the social development of the colony, even before Federation. One of these is a view of a military camp in Meeanbah, Pinkenba (1899): the line of cavalry horses and the tents behind are seen in a dramatic diagonal that lends itself well to the three-dimensional illusion of the stereoscopic viewer.

These were mounted infantry bound for South Africa to take part in the Boer War, to which all six of our colonies contributed troops, well before an Australian national army had been thought of. The ability to send troops to the aid of the Empire was a sign of growing social and political maturity.

Elliott was a patriot, but for his generation Australian patriotism was inseparable – even after national autonomy was granted with Federation – from the sense of belonging to the family of the British Empire. And so a number of other pictures commemorate royal visits, or temporary triumphal arches set up to welcome the Duke of York in 1901 or later the Prince of Wales in 1920.

Of course not only imperialism and patriotism but even the celebration of the growth of a colonial city where nothing had existed provoke a certain angst. So the curators have felt it necessary to commission a number of works by contemporary artists “to unpick the nuance and bias found within the Elliott collection”. The results are not surprisingly of variable quality and visitors will probably not be greatly enlightened by them.

Elliott’s pride in his country and the greater Empire were far from unusual for his time; they were indeed typical of the people who founded our nation. Today, the situation is different, and almost a generation of self-flagellation and dolorism in universities and schools has left most young people with little idea of what their country even stands for, let alone pride in its values.

Patriotism, as Dr Johnson famously said in 1775, can be “the last refuge of scoundrels”, but he made this remark in an attempt to distinguish true from false patriotism. The recent discussion about the majority of Australian schoolchildren failing a subject called “civics”, and the further revelation of how poorly the subject has been conceived, are cause for serious concern.

It is vital for young people to be raised with an appreciation of the values of the community to which they belong. This is certainly not an excuse for denying the complexities and darker episodes of any nation’s history. But it is important to make young people understand that, imperfect as Australia is, there is no better country in the world to live in, when we consider democratic institutions, the protection of the rights of minorities, the rule of law, the functioning of civil society and the provision of welfare and social services. If they have been told otherwise, their teachers have misled them.

New Light: Photography Now + Then, Museum of Brisbane, until October 6.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout