Our journey to diversity via migrants keen to nation-build

Hopes and Fears traces the successive waves of migration that made Australia a more harmonious multicultural nation.

In the past decade or two but especially since Covid, when too much isolation and time alone with our screens led to a national spike in collective neurosis, Australia has been in a state of anxiety about its own history, identity and future. Suddenly everyone began repeating formulaic acknowledgments of country at every opportunity; gallery and museum websites forced visitors to pass through a veil of contrition to find the information they were looking for; we started referring to Indigenous people as “First Nations”, a peculiar misnomer apparently imported from Canada. Sentimentality and hypocrisy overwhelmed what we used to think of as dry and laconic Australian common sense.

A chapter I contributed to a book in the past couple of years was looked over by what is now called a sensitivity reader; then the final draft was reviewed by a “First Nations reader”. Fortunately the text came through relatively unscathed, but this was exactly the kind of censorship the Catholic Church once enforced: a text could be looked at by a theological expert and if it contained no heretical opinions it was given the “nihil obstat” stamp (literally, “nothing stands in the way”); further review by a higher clerical authority would give it the imprimatur (“let it be printed”).

One the few substantial matters raised by the sensitivity censor was that they preferred to use the word colonist rather than settler, to avoid the suggestion that the land was unsettled before the arrival of Europeans.

I have observed before that the Left hates colonists and settlers – not to mention invaders – but loves migrants and refugees, yet in the long run all of these categories overlap to a considerable degree.

Throughout history, invaders often have been refugees themselves, fleeing from a superior enemy or from natural catastrophes. In Australia, in particular, the first settlers were deported convicts and their guards; in later generations many were economic migrants, leaving conditions of poverty and seeking a better life than they could have at home. And with the economic migrants we have also had periodic waves of political refugees.

But it is worth pondering the question of colonists and settlers because the etymology of the first word, perhaps unfamiliar to many readers, is significant.

It comes from the Latin verb colo which primarily means to till the earth and is related to the English cultivate, which also suggests some of the many extended meanings that the word can have in Latin too (to venerate the gods; to cultivate a friendship).

It is also the root of the words culture, agriculture – the tilling of fields – and later culture in the anthropological sense of the collection of beliefs and practices characteristic of a given people. From this original verb comes the Latin colonus, which means a farmer, or by extension someone who settles in a new land and farms it, as a member of a colony. The verb thus acquires the meaning “to inhabit”, for farmed land is inhabited land, and incoles means inhabitants. And this casts an important light on the way the Indigenous people first appeared to us.

Although the doctrine of terra nullius was not invoked in the early settlement of Australia (it was first used much later to limit the territorial claims of the squatters), the European conception of inhabitation was intimately grounded in the practice of agriculture: the Indigenous people manifestly did not plough the earth and raise cereal crops, and therefore have permanent towns and villages.

This must have coloured the general perception of them, even though government clearly asserted from the outset that their rights were to be respected and that British law was to apply equally to both natives and settlers.

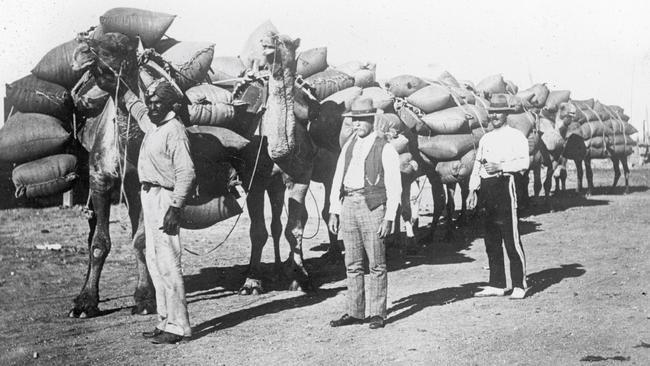

The National Library of Australia’s exhibition Hopes and Fears: Australian Migration Stories, at any rate, is about the successive waves of migrants who came to Australia over what is now approaching a quarter of a millennium – whether as farmers, which is indeed a recurring theme, or as miners, construction or white-collar workers – the myriad and increasingly diverse people who today constitute the vast majority of the Australian population.

Drawing on the library’s vast holdings, the displays include fascinating material that charts the changing attitudes to migration and especially to the groups of people who were, at different times, deemed most suitable to contribute to the nation’s growing population.

The first settlers to arrive here, in the year before the French Revolution, were not sent out to found a nation, to occupy the continent or even to establish a city. Sydney was intended as a penal colony, and even two decades later, when Lachlan Macquarie was governor (1810-21), he was criticised for spending too much money on ambitious building projects, more suited to a substantial urban centre and indeed a network of towns than to a prison.

But Macquarie was not the only one to conceive grander plans; by the 1820s Sydney already had the Royal Botanic Garden (1816), the first incarnation of the State Library (1826) and the Australian Museum (1828), together the first educational and scientific institutions in Australia. The University of Sydney was founded – in College Street and what is today Sydney Grammar School – in 1850.

Soon there was agitation among the free settlers to stop the transportation of convicts; but after its cessation in NSW in 1840, the necessity of attracting more suitable free settlers became apparent. A few years later, the gold rush in 1851 – just after Victoria had achieved separation from NSW – enormously increased Australia’s population in a short time: from about 430,000 in 1851, the population grew to 1.7 million in two decades, and by the 1880s was more than 2.25 million.

This influx of migrants, however, raised the first serious questions about the ethnic groups considered desirable or undesirable as future Australians.

By 1855, 17,000 Chinese had come to Australia, to look for gold or to work as labourers or set up shops and businesses. Tensions periodically erupted in riots and governments soon began to enact laws to limit Chinese immigration; these were repealed in 1867, but trade unions and others continued to be concerned about the Chinese willingness to work for lower wages, which was an important basis for the so-called White Australia policy. Anti-Chinese propaganda in various publications is epitomised here by a famous cartoon, Phil May’s The Mongolian Octopus (1886), which implies that the Chinese, as well as depressing wages for the working man, bringing diseases such as smallpox, spread corruption in our institutions and tempt women into prostitution.

White Australia sentiment is stridently expressed in another item, the sheet music for a song celebrating the idea of “Australia, the white man’s land” (1910), which incidentally illustrates the verbosity of contemporary posters and printed matter of this kind. On the other hand a more serious publication, Edward William Foxall’s Colorphobia: An Exposure of the White Australia Fallacy (1903), argues that racialist policies betray the ideals of liberal democracy.

One of the most interesting documents in the exhibition is a map titled The Flow of Population (1920), which tells us that the “average yearly migration from Europe during the five years ending June 1912” was 910,570, and asking “where did they go?”. The answer, graphically illustrated in red arrows of different thickness, turns out to be: 63 per cent to the US; 17 per cent to Canada, 12 per cent to South America and only 5 per cent to Australia.

But the most important message of the map is that the population of the Earth is rapidly increasing and that unless Australia builds a large enough European citizenry it will inevitably be overrun by migration from an Asian region whose own population is growing at an unsustainable rate.

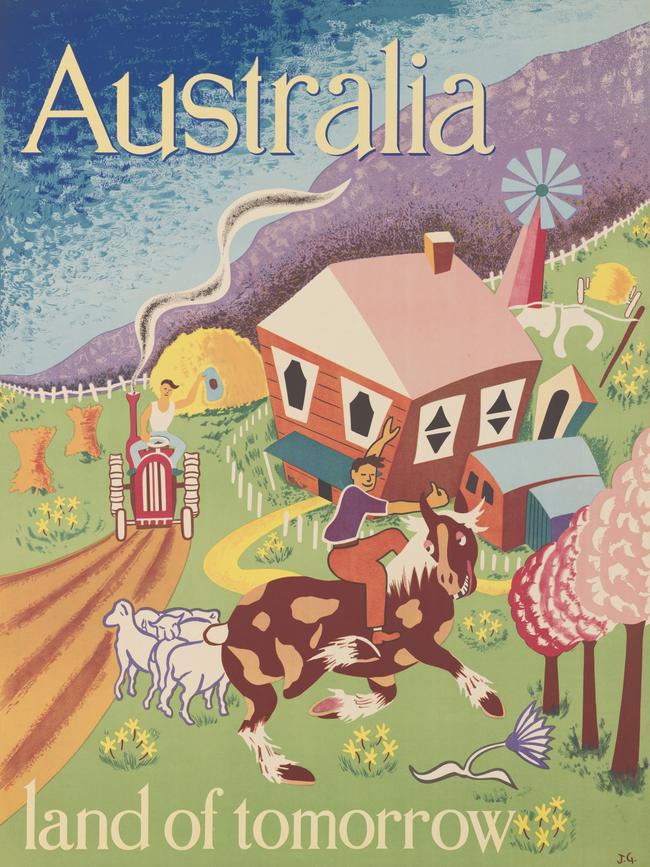

One result of the fear of uncontrolled Asian migration seems to have been a far greater openness to migration from anywhere in Europe, foreshadowing migration movements across the next half century, and leaving behind the idea of a purely British Australia, as promoted only a decade earlier in the jingoistic song already mentioned. But there was still an emphasis – recalling the etymology of the word colonist – on encouraging men to come out to Australia as farmers; for almost a century governments had sought to build a stable social base of yeoman farmers, rather than proletarian labourers working on the enormous properties of wealthy squatters; as the words of Advance Australia Fair already put it in 1878, “we’ve golden soil and wealth for toil”.

Several leaflets in the exhibition allude to farming: one of these encourages settlers in the north, Tropical Agriculture in Australia (1921); another is titled Australia’s Irrigation Enterprises (1924); and a third promotes employment opportunities in Australia’s timber resources (1924). But two of the most interesting are a decade or so older: How to Go on the Land in NSW (1909) and From Labourer to Landlord (1910), based on the experience of one British migrant, with a cover significantly showing a young man driving a plough through some freshly turned soil, while an inset photograph hints at the comfortable homestead the migrant can look forward to earning by his hard work.

Several posters advertise sea passages to Australia, including a P&O poster from 1928 offering fortnightly sailings via Egypt and Ceylon; the Aberdeen and Commonwealth Line offers one-class only passages via the Suez Canal (1932), illustrated already with an image of the newly completed Sydney Harbour Bridge; and the Commonwealth Government Line, established by prime minister Billy Hughes after the Great War, offers the “fastest passenger cargo service” on a rather austere and no-frills poster (1918-23).

Finally, after World War II, a poster advertises the £10 assisted passage scheme established by the Australian government in 1945, which brought a new influx of the so-called ten-pound Poms (1960).

But the government was no longer solely focused on British migration; during the war it had decided to increase the population of the nation by systematically encouraging immigration from other parts of the European world. More than 3000 migrants worked from 1947 to 1952 building hydro-electric power stations in Tasmania; but, most important of all, more than 60,000, especially from southern and eastern Europe, came to Australia to work on the Snowy River Hydroelectric project from 1949.

This project is rightly seen as a crucial stage in building a harmonious multicultural population, and indeed the whole exhibition shows how a British colony was ultimately able to overcome prejudices and open itself to a broader and more tolerant conception of what it could mean to be Australian – yet reminding us how lucky we are to have been settled by the nation with the most progressive and adaptable model of liberal democracy in the world.

Hopes and Fears: Australian Migration Stories

National Library of Australia, Canberra, to February 2

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout