Images have been manipulated since the earliest days of photography, as this exhibition highlights

Images have been manipulated since the earliest days of photography, as this University of Sydney exhibition highlights.

The strongest claim that photography could make, from its first invention around the time that Queen Victoria came to the throne, was its veracity. A photograph, after all, is a direct imprint of the world – or of the light reflected from objects in the world – on to the photographic plate. In principle, no image could be more objective, and pictures of crime scenes are still frequently taken by police photographers using analog cameras.

But this veracity led to a fascination with illusion and appearance, and stereographic photography, for example, developed very soon after the first cameras. The public was entranced by the illusion of three dimensions, the feeling that they were looking at the world itself. At the same time, photographers began to exploit special effects to make their images less literal and more poetic.

This pictorialist movement was opposed, in the interwar period, by new forms of naturalism, whether motivated aesthetically, as in the case of Anselm Adams, or in the cause of documentary authenticity and social realism. But even Dorothea Lange’s famous shot Migrant Mother (1936) is one of a series, chosen from the proof sheet because it told its story most effectively. This was not deception but a kind of fiction for the expression of truth.

There were others between the wars, especially in Soviet Russia, for whom fiction was brazenly a way to propagate lies. In the post-war years, the manipulation of photographs for political and commercial purposes increased steadily until the new digital technology of the last couple of decades of the 20th century made the adjustment and enhancement of photographs in media and advertising a standard practice.

The consequence of all this was that even by the end of last century, photography was less associated with authenticity than with illusion and manipulation. Many of the world’s most prominent art photographers, in consequence, based their work on deliberate and conscious theatricality, like Bill Henson, or quasi-cinematic artifice, like Jeff Wall or Gregory Crewdson, or even more elaborate constructions of illusion, as in Thomas Demand’s interiors constructed from cardboard and then photographed as though they were real environments.

Recently – perhaps even in the past year – the authenticity of the photographic image has become incalculably more questionable. With the advent of artificial intelligence, we are no longer faced with the falsification of imagery, its dishonest enhancement or fraudulent redaction; we are now dealing with technologies that can call up whole worlds of imagery from mere vocal prompts. In the Ballarat International Foto Biennale a few months ago I discussed the category dedicated specifically to AI images, or what some have called “promptography”. But that was already using old technology. In February we saw the first results of the new Sora program, which could produce a vivid image of woolly mammoths galloping through a snowstorm merely from a verbal description.

This is a technology that is changing our world and our sense of reality before our very eyes. It has already made it virtually pointless to set homework or research tasks at school or university. It will most likely eradicate countless jobs, although they will perhaps be lost not to the technology itself but to people who know how to use it. The social and political consequences, too, are vertiginous, when fraudulent images can be instantly transmitted and widely disseminated by social media.

Meanwhile, the dramatic transformation in the technologies for the production and publication of images has no doubt motivated a greater interest by historians and curators in what could previously have been considered eccentric and marginal areas of photographic practice, such as those that are the subject of this exhibition at the University of Sydney’s Chau Chak Wing Museum, The Staged Photograph.

Even the most straightforward portrait in the earliest days of photography was in reality staged to a certain degree, if only because the long exposure required the subject to sit very still for some time. The first daguerreotypes needed an exposure of about 20 minutes; by the early 1840s that was reduced to 20 seconds – even so, a long time to sit completely motionless. Some studios had special braces to support the head while posing. And all of them had painted backdrops, columns, balustrades and other picturesque elements of stage decor.

Some of the pictures in this exhibition are similarly portraits in various forms of costume, whether uniforms or fancy dress; thus there is a group portrait of four men in what are presumably their respective military and naval uniforms; on the other hand there is another portrait of a man, taken in Melbourne but dressed in Turkish costume, that probably recalls time spent in the Ottoman Empire.

There are numerous pictures of children: here a little girl in a bathing suit with a bucket and spade, but taken in a studio with a misty painted backdrop; there two other girls dressed as fairies or another couple who seem to be in costume for a play. A young woman poses as the personification of Britannia, another as Australia, with a Southern Cross headdress, and a third, this time photographed outdoors, holding a sheaf of wheat and a banner proclaiming that she is Victoria.

The most interesting part of the exhibition, however, and the one that raises the most questions for the viewer today, is devoted to stereographic photographs – already mentioned above – as a form of mass entertainment. Normally photography is monocular, but the technology was almost immediately adapted to mimic real binocular vision: this entailed taking two shots at the same time but offset horizontally by the equivalent of the distance between our two pupils. The resulting pair of images then had to be looked at through a viewer that allowed each to be seen separately and combined in the visual cortex to produce the illusion of three dimensions.

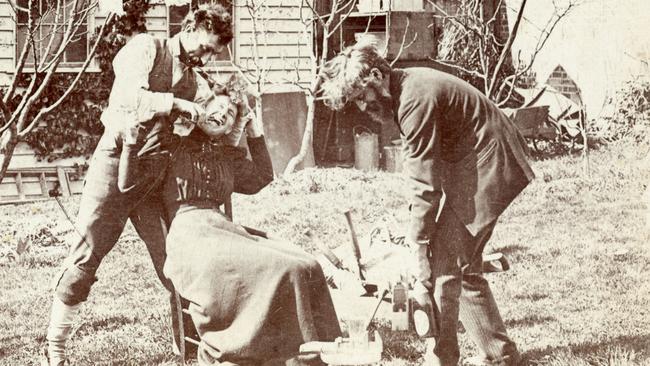

The public was evidently entranced by this illusion, and entrepreneurs produced series of famous landscapes, mountain ranges and other beauty spots of the world, as well as documentary series covering, for example, life in Australia’s gold diggings. But as we discover here, they also issued sets of humorous and anecdotal images that must have appealed to a contemporary public, probably of the poorer classes, since they were produced in great quantities at a very low price.

There is, for example, a page from a Sears Roebuck catalogue from 1906, advertising “A Great comic series” of 100 stereoscopic coloured pictures for only 85c. We are assured, in an exceptionally wordy text, that these are the “funniest pictures ever produced by the camera”, and that although “side-splitting”, they are in no way vulgar. We do not have the opportunity to judge for ourselves in this case, but the pictures that follow undoubtedly represent the same kind of thing.

Among the “side-splitting” scenes we are offered are a series about a woman pouring hair-restoring oil on to her husband’s bald head to no avail, before resorting to a wig instead, and a joke about dim Irish maids so popular that there are versions by two photographic studios: the mistress of the house has asked for the boiled potatoes to be served undressed, so the unfortunate lass comes into the dining room with the dish, dressed only in her bloomers, to the mixed amusement and shock of the dining guests.

One of the most interesting and even important questions raised by this exhibition is why contemporary audiences found these scenes hilarious, while to us they seem depressingly unfunny. It is not simply because of the passage of time, for we still respond to the humour of Aristophanes 2½ millennia ago, as well as to that of Shakespeare, Moliere, Voltaire, Jane Austen and countless others. Some of these buffoonish scenes were made around the same time that Oscar Wilde produced the most exquisitely witty comedies ever written.

Nor is it simply, as a wall label suggests, that we feel uncomfortable about laughing at national stereotypes today. The real problem seems to lie in the static nature of the photograph; a few of these gags might have been funny on a music-hall stage, executed with the timing that is almost everything in humour. Here there is no timing, and the desolate banality of the idea is laid bare, like a cadaver on an autopsy table.

Clearly the one thing that compensated for this, at least in the minds of the semiliterate mass audiences for whom these products were intended, was the astonishing three-dimensional illusionism offered by the stereoscopic process. Timing was, so to speak, replaced by spacing. And this must also explain the appeal of the hundreds of dreary and plangent scenes of courtship, marriage and baptisms, already criticised as early as 1858 in a text reproduced in the exhibition: “The enormous run which silly ‘Christenings’, sentimental ‘Weddings’ and namby-pamby ‘Broken Vows’ have, is really astonishing … The one reason for their popularity is that the stereoscope is ‘the poor man’s picture gallery’ … many … have felt such a pleasure in beholding objects standing out in relief that they have become enamoured of anything stereoscopic … and as weddings and that class of composition have appealed to the sentimental feelings of the young-lady portion of the public, there has arisen a great demand for that class of picture.”

The author may have been thinking of James Elliott’s Broken Vows, issued a year earlier in 1857, and itself inspired by a painting of the same title by PH Calderon which is today in the Tate Gallery. Calderon’s painting has a young lady overhearing her fiance flirting with another girl behind a garden wall and emphasises the moment of heartbreak; Elliott’s photograph leaves nothing to the imagination but shows the jilted girl just outside the church where her faithless lover is marrying another.

Just as men may have guffawed at the Irish maid, no doubt young women wept at images such as this; and both may have pondered the moral warning of another of Elliott’s compositions, A Week after the Derby (c.1855-60), in which we see a formerly respectable middle-class family ruined by gambling on the horses, slumped in despair as a bailiff and his clerk assess the value of the furniture that will be sold at auction to pay the profligate husband’s debts.

Pictures such as this were mass-produced versions of the ponderously moralising paintings current at the same time, like Holman Hunt’s The Awakening Conscience (1853). But it is interesting to see that stereography was so popular that it could even become its own subject, in yet another composition by Elliott that shows a family gathered in the evening to view stereographs; although it is unclear whether this is really evidence of their popularity among the upper classes or simply, as seems to be the case elsewhere, a chance to offer a mass audience a glimpse of life among the more affluent.

The Staged Photograph

Chau Chak Wing Museum, University of Sydney, to August 4

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout