Lives in pictures at the 2021 Ballarat International Foto Biennale

From behind-the-scenes photos of The Beatles to random Flickr images, the Ballarat International Foto Biennale has much to say about our contemporary obsession with photography.

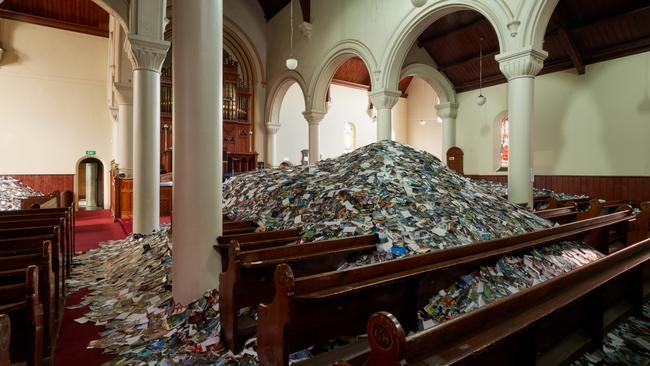

Imagine a space filled with 350,000 photographs; not images on a screen but glossy paper ones of the old-fashioned sort, piled up in huge drifts, cascading across pews (we’re in an old church) and ankle-deep on the floor. You can walk through them, roll in them, pick them up. Some people even pocket them.

You scrutinise one of the snaps; a group of strangers smile at the camera. Is it a party? A family gathering? What country are they from? Here’s another of a baby. And another of a cobbled street somewhere in Europe.

Dutch artist Erik Kessels is fascinated by the randomness yet strange predictability of everyday images and the vernacular language of amateur photography.

Housed in an old Uniting Church in the centre of the city, his installation 24 HRS in Photos is one of the drawcards at this year’s Ballarat International Foto Biennale.

All of the photographs were downloaded in a 24-hour period in 2011 from the image and video hosting site, Flickr; random images, as many as possible in the time frame.

Back then image-sharing sites were relatively new. Flickr had been founded in 2004, Instagram in 2010. In the past decade, sites such as these have become ever more ubiquitous, the volume of our viewing habits increasingly dizzying. Not everyone was posting and sharing pictures of their breakfast or cat back in 2011.

Today, 100 million photos are posted on Instagram every 24 hours.

But despite the social revolution wrought by technology, Kessels says the photos hardly deviate from those our parents or grandparents took.

“Holidays, sports events, landscapes, children, portraits; the pictures are a total mix of all the stereotypes,” he says. But those tropes, however conventional, contain an individuality multiplied by the tens of thousands, he adds. And for Kessels, famous for his installations of photography found in everyday life, the digital revolution has been a fascinating phenomenon.

“We take more photos before lunch than most people in the 19th century took – or had taken of them – in a lifetime,” he comments and, he adds, we’re no longer making records for posterity to put in the family album but using photographs as instant, shareable stories, as an aid to shopping, or to remind us where we parked the car.

“We’re consuming without digesting,” he says, and the boundaries between the private and the public are increasingly blurred.

“It’s very democratic, everyone has a chance (to share); but while a family album only had a few eyes on it, today the opposite is true. But for me, it’s fantastic, it’s visual anthropology.”

If Kessels’s installation represents the democratisation and sharing of photography, Linda McCartney: Retrospective celebrates privileged access.

As a photographer of 1960s rock ‘n’ roll celebrities such as Jimi Hendrix, the Rolling Stones and Janis Joplin, Linda Eastman, as she was then named, already had a growing reputation when she came to photograph The Beatles on a work trip to London in 1967. Two years later she married the band’s Paul McCartney.

Alongside evocative photos of the music scene, including very exclusive access to one of the most famous musicians of the 20th century, the 200 images in this exhibition capture her reportage work and the private world of family life and friends. The exhibition also includes a series of prints from family trips to Australia in 1975 and 1993 that have never been exhibited.

Fiona Sweet, BIFB artistic director and CEO, says the McCartney collection is undoubtedly the popular drawcard of this year’s Biennale and Linda McCartney is, emphasises Sweet, an exceptional talent.

“She was already on assignment photographing important celebrities and had an incredible ‘in’. She’s a beautiful photographer who can take candid pictures of musicians and poets and actors who were creating at a time of major change,” she says.

One of McCartney’s talents was to melt into the background and take fly-on-the-wall pictures. An intimate shot of John Lennon and Paul McCartney sitting side-by-side in a studio; a mother and fractious child on a beach; people on the street shot from car windows, pop stars goofing about.

A candid video interview accompanies the stills, in which both Linda and Paul talk about their relationship, their friends and being a photographer when you’re married to one of the most famous men on the planet. Being a fly on the wall became a whole lot more difficult.

The exhibition also looks at McCartney’s animal activism and her promotion of vegetarianism.

McCartney died from breast cancer in 1998 at age 56 after 29 years of marriage.

The show is curated by Paul McCartney and two of their daughters, Stella and Mary, and Sweet says that conversations about securing this exhibition go back five years.

When Paul McCartney came on tour to Melbourne, she says “he sent one of his people up here and we showed him the space”.

She had to convince the McCartney Archive in London that Ballarat and its biennale was a worthy destination.

“I was really talking it up, as ‘the regional arts capital of (Melbourne) the arts capital of Australia’,” she says.

There are several contenders for the title of Victorian regional arts capital but Sweet, who took the helm in 2016 and who leaves at the end of 2021, says she always aimed to make the gold rush town a must-visit cultural destination. A 90-minute drive from Melbourne, it’s a small city famed for its 19th century architectural grandiloquence, imposing art gallery and bracing climate.

The Biennale, which started in the nearby town of Daylesford in 2007, before moving to its bigger neighbour in 2009, has grown to be part of the international biennale scene and is a member of the Asia Pacific Photoforums.

On taking the job, Sweet says she saw the potential for a year-round photographic presence. In 2018 she started raising private funds and last year the state government backed a permanent home for the BIFB and the creation of the National Centre for Photography, with funding of $6.7 million.

This suite of galleries, housed in the former 1860s Union Bank building in the city centre and currently undergoing restoration, is already hosting Biennale exhibitions. When the Centre opens as a permanent venue in 2023, it will be a major cultural boost to the city and region, says Sweet.

Interest in photography is at an all-time high, she emphasises, and our obsession with taking and sharing multiple images daily has not only made the average person a better photographer but also raised their appreciation of the medium.

“It’s allowed the photographer to become far more important and significant in terms of working within the art realm,” Sweet says.

“There’s a greater appreciation of the photographic craft and contemporary artists are using the medium in different ways and using it to tell stories. We see it overseas at biennales around the world – a huge number of works are now photographically based”.

The Covid-19 resurgence and subsequent state lockdown cast a pall across the opening, originally slated for August 28 but the Biennale’s duration was extended from October to January. “Now that people can travel again, they’re coming in droves,” she says.

So what’s in store for those who can now come in person?

Image immersion, she says, from the moment they arrive.

Alongside the curated program, there are 89 exhibitions in the city’s bars, cafes businesses and laneways, featuring the work of emerging and established photographers.

These are selected by the businesses themselves and unite the community behind the Biennale.

“It’s superbly popular, the whole place is filled with photography and of course it pulls in a lot of local people coming to see friends’ work,” she says.

The eclectic choice of venues is echoed in the 29 exhibitions which form the curated program.

Number One, billed as an ode to the recently deceased founder of Mushroom Records, Michael Gudinski, is another rock-celebrity show; it’s accessed through a trap door into the vault of the Mechanics’ Institute.

Say it with Flowers, a group show exploring mortality, mourning and community curated by Wotjobaluk artist and writer Kat Clarke, is at Ballarat General Cemetery.

Other exhibitions such as Notes from a Queer Mystic featuring American Steven Arnold, create their own environments; a protégé of Salvador Dali, Arnold was a filmmaker and multidisciplinary artist and his 1980s photographs conjure a fantastical world where androgynous, mythological characters are part of elaborate and surreal tableaux vivants.

The Poverty Line is an exhibition that undercuts the glitz and glamour with a sociological look at food and hunger around the world.

Devised by Beijing-based photographer Stefen Chow and economist Huiyi Lin, the premise is simple; between 2010-2020, they photographed the food choices of those on the poverty line in 36 countries and territories spanning six continents.

From Brazil to China they visited local markets, buying the amount of food an individual could afford per day based on the respective poverty line definition set by each government. In developed nations it was the proportion of total income spent on food, in poorer countries the entire daily income of an individual was used. After placing the resulting pile of food on a page of a local newspaper from that day, they took a photograph.

The inequality is stark.

In Sydney, Australia, one of the earliest countries visited, out of a daily income of $31.08 in 2011, $7.52 (US$8.02) went on food. This is symbolised by a roast chicken lying on a copy of The Australian.

In Laos (a pile of snake beans) the poverty line income is US$0.80. China’s poor (their food intake symbolised by a picture of steamed buns) had, in 2016, a daily income of US$1.27. In Norway it was US$10.26.

Calculations of what constitutes poverty are complex and politicised, says Lin; in poorer countries many more people live below the poverty line and can only aspire to the meagre diet of those slightly wealthier.

In richer countries, other issues came up, says Chow. “We realised that in developed countries, there are lots of choices and it’s not just about food choices but about the income gap and division of resources,” he says. “Some of the richest countries have the biggest income gaps”.

This multiplicity of viewpoints is what makes photography such a powerful medium, says Sweet and unlike art, photography attracts a crowd that doesn’t necessarily frequent galleries or other cultural institutions.

“In 2017, 41 per cent of audiences had never been to Ballarat and 60 per cent had never been to a festival,” she says.

“Some visitors wandered in to look at the work while eating their lunch; it shows they don’t know the rules, but we want that,”she adds; “photography is an egalitarian medium and it reaches people who don’t necessarily believe art is of any value.”

The Ballarat International Foto Biennale is showing until January 9, 2022.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout