Richest 250 - WiseTech founder Richard White and his world of philanthropy

WiseTech’s Richard White wants to beef up Australia’s STEM capacity. He’s setting up a new technology education foundation to get the ball rolling.

The List is the biggest annual study of Australia’s 250 wealthiest individuals, with final figures calculated in late February 2022. See the full list here.

For Richard White, it seems obvious to use both the financial assets he has created from a successful career and the business nous he has accumulated when it comes to philanthropy.

White is the founder of WiseTech Global, the logistics software company he started in 1994 and turned into a market darling as one of the most successful ASX floats in recent decades.

WiseTech has also made White extremely wealthy, but running a successful worldwide software company from Australia has also opened his eyes to what his industry can do for its employees and his home country. Which is why he wants, in short, to put his money where his mouth is.

“I have benefited greatly from the development of my digital skills and knowledge, and made more money than I ever thought anyone could reasonably make in a lifetime,” White tells The List. “So why not take the things that I have been rewarded with and give back something in the process?”

Australia's Richest 250

Rinehart tops Richest 250, Canva’s Perkins the big mover

The top 10 on The List are wealthier than ever before, led by two of the country’s most successful businesswomen who have changed the face of corporate Australia.

Can restaurant king Justin Hemmes take on Melbourne?

The Sydney bar tsar reveals what his plans are for expanding his empire beyond his home turf.

How dark moments gave birth to vast Canva fortune

The Canva founders were rejected by more than 100 investors before they got their first ‘yes’.

Newcomers: The 29 wealthy debutants making their mark

Meet the little-known powerhouses, including one worth $1bn, who made The Richest 250 for the first time.

‘One service station was never going to be enough’

For Nick Andrianakos, a ‘journey of discovery to the lucky country’ has led to an estimated $894m petroleum fortune built over a lifetime.

Retail lobs into the ‘Meccaverse’

For Mecca founder Jo Horgan, there’s nothing so ‘viscerally delightful’ as going into a store and playing with products.

Tech guru Richard White’s plan to give back

WiseTech’s Richard White wants to beef up Australia’s STEM capacity. He’s setting up a new technology education foundation to get the ball rolling.

How ‘snowmobile approach’ made Bonett a billionaire

Online gift card billionaire and commercial property magnate Shaun Bonett says there are very few people who invent things. The real art is in putting things together in a better way.

Bevan Slattery kicks off his last hurrah

If Bevan Slattery’s has big plans: to pull off what will be the largest private digital infrastructure project in Australia’s history.

‘I just love anything that’s difficult’

If it sounds too good and big to be true, unstoppable property developer Lang Walker knows it’s the project for him as he loves nothing more than proving the doubters wrong.

The fortune four million parcels built

Meet the little-known powerhouse behind Australia’s burgeoning e-commerce industry.

How our billionaires relax

It’s not all work for the big players on The List: The Richest 250. They wind down in various ways, from the sporty to the leisurely – or just collecting ritzy houses.

Simple lessons in David Dicker’s 25-year overnight success

It took until the fast car enthusiast was 50 to realise what he needed to change to be a success in business – pay staff well, hire more women and stay out of the way. The results have been startling.

How Culture Kings founders made millions

Australian retail phenomenon Culture Kings is about to launch its biggest play, with its 30-something founders taking on the US market.

Gina Rinehart tops The List as NFT revolution takes off

This year’s edition of The List - Australia’s Richest 250 will show how mining and technology are now the country’s two most successful sectors.

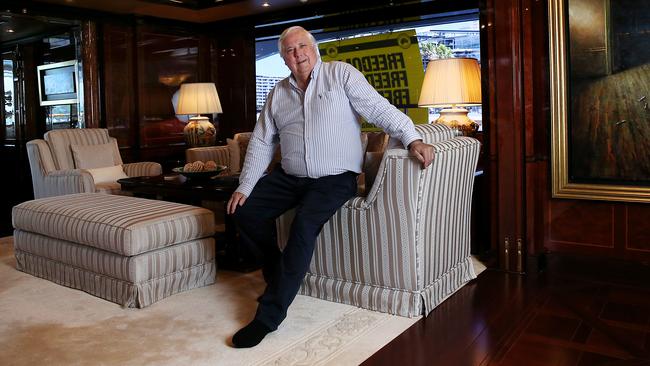

Cars and politics fuel Clive Palmer’s passion play

Clive Palmer makes more income than almost every other Australian billionaire. But how he chooses to spend it is unique.

High flyers: Private jets the new toy of choice

Forget fast cars, super yachts or luxury houses. The hottest trophy asset for Australia’s rich elite right now is a $100m jet. So who has bought one?

White has established a new technology education foundation with an initial $50 million donation, though he says that figure is only a starting point. He also eventually wants other technology leaders to feel free to contribute to the foundation and its cause as well, arguing that he doesn’t want to undertake the endeavour just for personal glory.

The foundation will fund the development and teaching of STEM courses, the integration of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, initially in high schools but hopefully later in primary and tertiary education, with the expressed aim of creating the next generation of technology industry workers and leaders.

“STEM I believe has direct applicability in life, and has a direct impact on what is necessary for Australia’s future. If I can help add a bit of money and management capability we can build what will be a conveyor belt of talent to better enable Australian companies to compete globally,” White says. “And I think education is the most long-lasting impact you can give to anyone.”

Members of The List pursue a full range of philanthropic endeavours. The nation’s biggest giver, billionaire mining magnate Andrew Forrest, has put $2.6 billion into his Minderoo philanthropic foundation, which distributed about $110 million last year. Minderoo is trying to help end slavery and cancer, funds Indigenous programs, and supports other causes such as removing plastic from the ocean and fighting the rise of artificial intelligence and its threat to democracy.

Judith Neilson supports a range of causes in the arts sector, and has funded a journalism institute. Her former husband, fund manager Kerr Nielson, donated $11.47 million last year to more than 50 arts and health causes, ranging from $3 million to the Art Gallery of NSW to $5000 to the Rough Edges community charity in Sydney’s Darlinghurst. Lang Walker made two $20 million donations last year, one to a new medical research centre in western Sydney and another to the Parramatta Powerhouse museum project. Frank Lowy and his family donated more than $50 million via their medical research foundation and put money into the Lowy Institute think tank.

White’s foundation is building a platform to provide full STEM curriculum coverage, designed to free teachers to actually teach

Peter Scanlon’s foundation has more than $150 million to distribute to various migrant causes, while Paul Little and wife Jane Hansen gave a $30 million gift to the University of Melbourne that includes the building of a residential hall and awarding of 20 full scholarships annually to high-achieving students who may otherwise be unable to attend the University.

“The program reflects Jane’s and my belief that future success should not be limited by any past disadvantage and that an individual’s life trajectory should be guided by their determination to achieve their ambitions,” says Little.

White’s foundation is building a platform to provide full STEM curriculum coverage, designed to free teachers to actually teach rather than having to spend too much time developing lesson plans and researching the syllabus.

It is also, White says, attempting to fill a gap in the job and skills market. A report released by The Tech Council of Australia last year concluded that Australia is 260,000 short of people with tech skills that will be needed by 2025.White believes that figure is probably even higher now, and educating students for tech jobs will also mean the need to import skilled workers for the sector will lessen as time goes on. “Tech jobs usually pay way above the norm, they are safe and secure, the sector has a long and deep and powerful future, and they are creative jobs. It’s not a job screwing lids on bottles or digging coal out of the ground. These are long-term valuable jobs for our citizens.”

See The List: Australia’s Richest 250

White’s platform is also being designed to extend beyond the curriculum to allow students interested in experiencing authentic job-related tasks to investigate more relating to programming, coding, data analytics, user interface design, cyber security, web design and artificial learning.

“I’ve been working in this STEM space since 2000 really, and we started by sponsoring individual students,” he says. “So we developed, me and the company, a lot of understanding on how things worked. We could see that the Australian education system had been very good at creating jobs for people, but not particularly strong at creating tech jobs. In 2010 we increased the sponsorships and started taking them to high schools, to connect with the national computer science school program each January for high-performing students, and kept pushing further and further into this.”

White says he found it was becoming more difficult for schools to move into “the very fast-moving areas” and quickly develop in the tech sector, and discovered after speaking to several teachers that many had little time to learn new skills and plan lessons. He also found that “for the students, sometimes they know more than the teachers do” when it comes to technology.

Hence the idea of creating the STEM platform that hopefully means the “teachers can get on with teaching”, White says, and make sure the content is relevant for future employment in the tech sector.

On that point, White harks back to his own high school days. “My father was an engineer and the factory he worked in was three blocks from high school. I’d walk down there every day after school and I’d learn all this stuff that was really relevant. I was learning about electricity and welding and mechanics, and it was all relevant to work I thought. I couldn’t always make that connection with subjects at school.”

White plans for the STEM platform to be rolled out for trials later this year at a small number of high schools in NSW – “we’re good at testing prototypes in tech” – followed by a national rollout. He has already held what he says have been positive discussions with the NSW education minister Sarah Mitchell, and education department officials in the state and also Queensland and Victoria.

He says he wants to provide all students, no matter where they live or what their circumstances are, access to a quality digital education and a clear pathway to develop decent tech skills. His program will initially target years 7 through 10, then upper primary and secondary schools, and eventually universities. He wants a particular focus on schools in less wealthy areas and regional towns.

While the program will be free, it is subject to working with bureaucrats and finding its way through what might be a maze of regulation – something that entrepreneurs in charge of their own businesses and used to calling their own shots may not always enjoy having to deal with.

When asked how he will cope, White does point out his own business experience might prepare him. “In international trade, you always have significant government intervention. In Australia there are about 25 government agencies we have to deal with, in America it is 35. Our software platform ultimately has to connect our clients with government, so it is not a huge distance from that to thinking about engaging with government about education.”

White is also keen to involve other tech entrepreneurs in his foundation, having structured it to make it scalable even if he intends to put more of his own funds into it over time and spend at least a decade working on it.

“I’m not attempting to own this space,” he says. “I’d want to bring in anyone who wants to contribute, whether it is personally like me or a company that wants to provide some of their profits to it. It is not just giving something, you get something back. A lot of technologists are socially minded and they know they have gained an advantage from society and they know they need to give something back.

“The tech industry creates such value and is so creative, and the people I know have a very similar attitude to me. Where we are slightly right or left [politically], all of us like what we do, and know we want to give something.”