Richest 250: How Clive Palmer spends it. Boats, cars, planes, property – and politics

Clive Palmer makes more income than almost every other Australian billionaire. But how he chooses to spend it is unique.

At first glance Clive Palmer seems like just any other billionaire. But appearances can be deceiving, and the lines between fact and fiction, truth and opinion can blur.

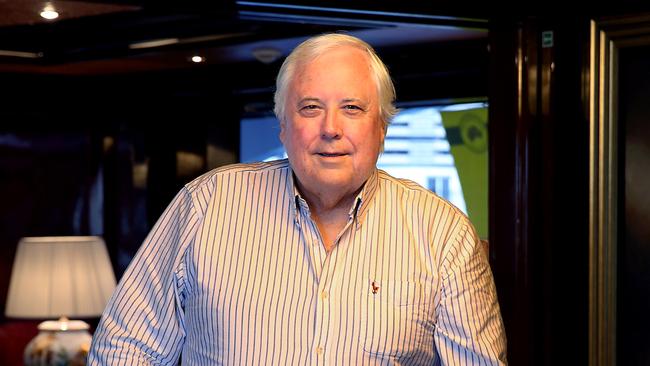

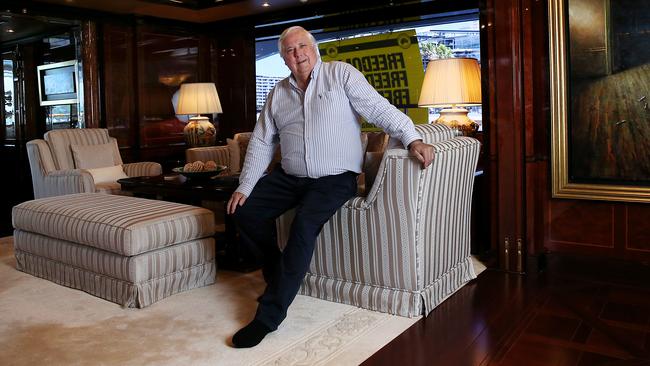

Palmer is sitting with The List aboard his $100m superyacht on Sydney Harbour on a bright mid-February afternoon. The weather is perfect for a sail, but the 56m yacht Australia is docked next to the swanky Park Hyatt Hotel at The Rocks and obscuring some of the views.

As they would with any huge vessel that towers over nearby restaurants and tourist attractions, passers-by are gawking. Which is probably why Palmer has attached signs for his United Australia Party political venture on the top floor of the vessel, just in front of the jacuzzi, outdoor seating and wet kitchen.

His other boat, the smaller 35m Sunseeker he bought from Larry Kestelman for about $12m two years ago, pulls in next to Australia. Its top level features two female models in swimsuits waving bright yellow UAP signs at tourists walking by.

The Opera House is in the background, the Harbour Bridge to our left as we look out across Australia’s deck. But business is at the forefront of Palmer’s mind at that moment. Like many others on The List, he is keen to discuss his considerable fortune in detail. And there is no doubt Palmer has amassed all the trappings of wealth that most billionaires collect, even if he does have more than most others.

There are the two boats, at least four jets, big property holdings in Queensland, especially around Paradise Point on the Gold Coast, where his primary residence is, and the Coolum Resort and golf courses earmarked for apartment projects. There’s a resort in Tahiti and rural property in Queensland, not to mention various mining tenement holdings that could one day yield coal. There are also warehouses in New Zealand and other property overseas.

And then there are the cars. “I’ve got the world’s biggest collection of vintage cars,” Palmer reveals. “They’re in Brisbane. I think the collection is worth about $230m at the moment. For example, we’ve got more than 22 vintage Ferraris, 120 Mercedes, 100 Rolls Royces and Bentleys. We’ve got the world’s only full collection of Rolls Royce Phantoms. We’ve got Bugattis and all these others.

“They’ve been a good investment, and they’re probably up 30-40 per cent during the pandemic. I’d probably get $400m if I sold them but I won’t, because I’ve been collecting since I was younger.”

Australia's Richest 250

Rinehart tops Richest 250, Canva’s Perkins the big mover

The top 10 on The List are wealthier than ever before, led by two of the country’s most successful businesswomen who have changed the face of corporate Australia.

Can restaurant king Justin Hemmes take on Melbourne?

The Sydney bar tsar reveals what his plans are for expanding his empire beyond his home turf.

How dark moments gave birth to vast Canva fortune

The Canva founders were rejected by more than 100 investors before they got their first ‘yes’.

Newcomers: The 29 wealthy debutants making their mark

Meet the little-known powerhouses, including one worth $1bn, who made The Richest 250 for the first time.

‘One service station was never going to be enough’

For Nick Andrianakos, a ‘journey of discovery to the lucky country’ has led to an estimated $894m petroleum fortune built over a lifetime.

Retail lobs into the ‘Meccaverse’

For Mecca founder Jo Horgan, there’s nothing so ‘viscerally delightful’ as going into a store and playing with products.

Tech guru Richard White’s plan to give back

WiseTech’s Richard White wants to beef up Australia’s STEM capacity. He’s setting up a new technology education foundation to get the ball rolling.

How ‘snowmobile approach’ made Bonett a billionaire

Online gift card billionaire and commercial property magnate Shaun Bonett says there are very few people who invent things. The real art is in putting things together in a better way.

Bevan Slattery kicks off his last hurrah

If Bevan Slattery’s has big plans: to pull off what will be the largest private digital infrastructure project in Australia’s history.

‘I just love anything that’s difficult’

If it sounds too good and big to be true, unstoppable property developer Lang Walker knows it’s the project for him as he loves nothing more than proving the doubters wrong.

The fortune four million parcels built

Meet the little-known powerhouse behind Australia’s burgeoning e-commerce industry.

How our billionaires relax

It’s not all work for the big players on The List: The Richest 250. They wind down in various ways, from the sporty to the leisurely – or just collecting ritzy houses.

Simple lessons in David Dicker’s 25-year overnight success

It took until the fast car enthusiast was 50 to realise what he needed to change to be a success in business – pay staff well, hire more women and stay out of the way. The results have been startling.

How Culture Kings founders made millions

Australian retail phenomenon Culture Kings is about to launch its biggest play, with its 30-something founders taking on the US market.

Gina Rinehart tops The List as NFT revolution takes off

This year’s edition of The List - Australia’s Richest 250 will show how mining and technology are now the country’s two most successful sectors.

Cars and politics fuel Clive Palmer’s passion play

Clive Palmer makes more income than almost every other Australian billionaire. But how he chooses to spend it is unique.

High flyers: Private jets the new toy of choice

Forget fast cars, super yachts or luxury houses. The hottest trophy asset for Australia’s rich elite right now is a $100m jet. So who has bought one?

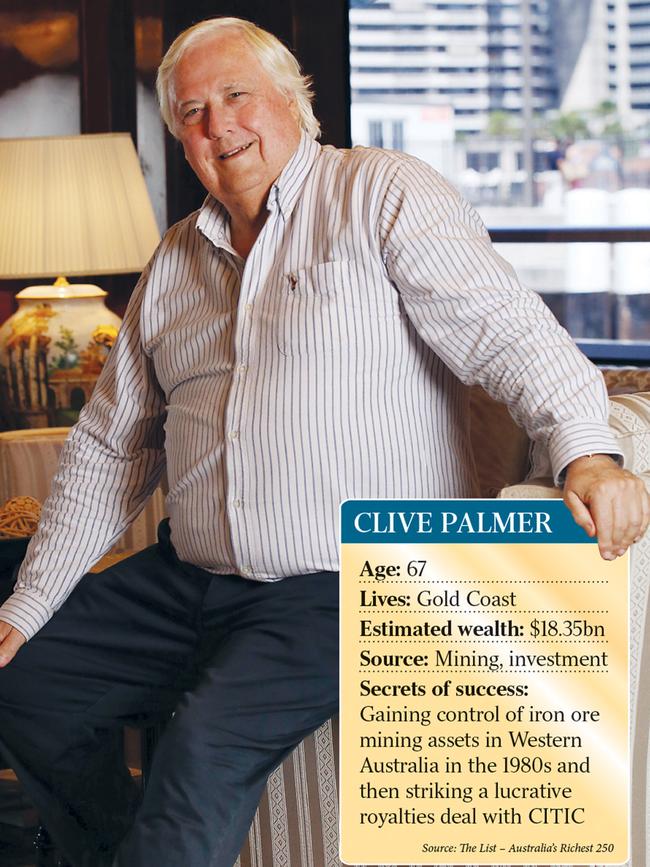

All that spending is possible because of the massive iron ore royalties that flow Palmer’s way every year, a cool $620m in cash courtesy of a canny yet controversial deal with Chinese mining giant Citic that has been the subject of much litigation. Only Andrew Forrest would likely make more annually, and perhaps Gina Rinehart, but those are via dividend payments dependent on company profits. Low-profile iron ore heiresses Angela Bennett and Leonie Baldock and Alexandra Burt also receive hundreds of millions each year in royalties.

But Palmer is likely to top the lot for years to come, as more iron ore is produced by Citic at its Sino Iron magnetite mining and port project near Karratha in Western Australia. It wants to export more iron ore, and the more it digs out of the ground, the more royalties flow Palmer’s way.

Palmer’s wealth reaches an estimated $18.4b this year, and he could just about buy whatever he wants. Why, then, is he spending more than $100m on funding the UAP’s federal election campaign this year, including tens of millions in political ads adorning billboards around the country, running during prime time television and seemingly before every YouTube video?

The answer to that is less clear. He can certainly afford it. “It’s only a couple of months’ work for me,” he deadpans.

Many dismiss him as a wealthy buffoon. There are the various legal battles he’s seemingly always locked in, worth up to $24bn if he manages to win the various actions he has against Citic and the WA government, according to his company Mineralogy’s financial accounts.

Memorably, there was the time his nephew Clive Mensink left Australia after the collapse of Queensland Nickel about six years ago and is yet to return from Bulgaria.

There are the giant replica dinosaurs he had installed on the golf course at his Coolum resort (and the battles with residents), and the plans he’s long had to build a replica Titanic. Billionaires can be eccentric and have unusual pursuits, but there is no one quite like Palmer.

There’s no one quite like him pursuing politics either, and it is something he has a history with. Palmer worked for former Queensland Premier Joh Bjelke Petersen in the 1980s, including a stint as his media spokesman, and was long a donor to the conservative side of politics after he claimed to have made good money in Gold Coast property that he later parlayed into mining holdings in WA’s Pilbara.

After becoming a billionaire, Palmer would win a seat in federal Parliament with his then Palmer United Party in 2013, which would for a time hold the balance of power in the Senate until he fell out with Senators Jacqui Lambie and Glenn Lazarus. He would leave politics three years later and deregister the party in 2017, but shelled out $88m in mostly negative advertising aimed at former Labor leader Bill Shorten in the 2019 election that has been credited in part with delivering victory for Prime Minister Scott Morrison and the Coalition.

Palmer claims he had no intention of re-entering politics until a chat around the middle of last year with controversial MP Craig Kelly, a former Liberal Party member who left to become an independent and is now leader of the UAP.

“I didn’t want to get involved, right. I retired from politics in 2016,” Palmer says.

“With recent developments, people have realised that politics plays an important role in their lives, and they have views they want to express. Craig Kelly said he was prepared to turn his back on his career with the Liberal Party and has a different view to the government on a lot of things. So I said, I’m prepared to put in $100m and see what happens.”

Palmer is running candidates in every seat, and has a senate ticket in each state and territory. He also writes all his own advertisements, and says he will target both the Labor Opposition and Liberal and National Coalition.

“I get up at 2am … and spent my first hour thinking about all the nasty things I can do to the Liberal Party or the Labor Party,” he says with a chuckle. “Then from 3am to 4am I actually do it, writing the ads and other things.

“I’ve got no confidence in Scott Morrison or Albo [Anthony Albanese], or [Treasurer Josh] Frydenberg or that other guy, what’s his name, [Opposition Treasury spokesman] Jim Chalmers. The Labor Party doesn’t know what to do. Scott Morrison is Scotty from Marketing. He’s prepared to say anything, but he has no content or character. He’s got no experience in the commercial sector. At least my job is dealing with large amounts of money.”

Some of Palmer’s strategies and policies sound relatively mainstream. He says he’s particularly concerned about the country’s high debt levels, and believes there’s a big danger of many Australians losing their homes if and when interest rates go up later this year.

He would enact policies to deal with a housing ownership crisis and make tweaks to the tax system to make it more friendly to small business should he be elected, he says.

Some of his theories are less shared among the wider public, even if Palmer claims his party now has about 84,000 members. At various points of the interview, though, Palmer warns of the danger of the adoption in Sweden of people having microchips inserted under their skin that can track their Covid vaccination status, and that the Labor Party and Liberals would somehow outspend him on advertising when the election campaign is on in earnest, even if they have outlaid only a fraction so far.

Palmer also claims to have met a couple in Queensland recently at a UAP function who told him that their two children dropped dead half an hour after they had received a Covid vaccination.

As to why he isn’t vaccinated against Covid, Palmer claims it is a “good thing” due to it “highlighting a point” that Australians can choose to be jabbed or not. “We’re not pro-vax or anti-vax, we’re pro-choice. I’ve exercised my freedom of choice. I’ve been informed consent, and I’ve decided I won’t be vaccinated. And that’s what I’ve done.”

It turns out that Palmer is probably staying on his superyacht in Sydney that week, when he is in the Federal Court taking legal action against WA Premier Mark McGowan alleging defamation, because his unvaccinated status would likely make it hard to enter hotels, restaurants and other areas. Palmer later tests positive for Covid and has a brief hospital stint.

When asked if he is prepared for long stints in Canberra should he be elected as a Senator, Palmer admits to no great enthusiasm at the prospect. He says he would be prepared to do so though, out of a sense of duty, listing the family members who died serving in Australia’s Armed Forces in World War II and others who have seen active duty more recently. “If you’re in a privileged or elevated position, through life or money, and you can see what’s happening to the country, you’ve got a duty and responsibility to let people know what’s going to happen.”

“I do acknowledge that it’s an unusual occurrence that someone in my position wants to contribute to the community. But if you’ve been successful and you know what is happening, and you’ve got some morality, then you want to share that with other people.”

Morality is not a word that some associate with Palmer, who faces fraud charges by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission regarding the movement of $10m in 2013 from his private companies to the Palmer United Party. Unsurprisingly, he gives a question about being considered a criminal by many in the community short shrift. “ASIC has had charges against me for 10 years now … and it’s a bit like what Paul Keating said when he was prime minister: ‘Let’s do them slowly’. They’ve charged me with criminal dishonesty … but on that standard you could convict every merchant in Australia.”

Yet is Palmer a menace to society, or a danger to democracy at least?

“Look, most Australians work hard. And they look at me and think ‘I’ve done everything I could do in my life to look after my family, so this guy must be a crook because he’s done better than I have. Well, there’s a general sort of cutting down of [successful] people I suppose.”

And with that, he is on to discussing valuations of the revenue stream he gets from the Citic royalties. There are listed companies in Australia, Canada and the US that are comparable, with mining royalties their main asset, and the valuation multiples they trade at are currently very high compared to other sectors. It all means that Palmer is extremely wealthy, which gives him the time and money to pursue those political interests.

He eventually admits that politics will at least keep him busy. “When you get to 67, your options are limited, right? You can play croquet, you can go and do bowls. You can hop on a bus and go and look at flowers. Or you can be engaged in politics at a national level like this.”

It remains to be seen if it will be money well spent.

The 2022 edition of The List - Australia’s Richest 250 is published on Friday in The Australian.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout