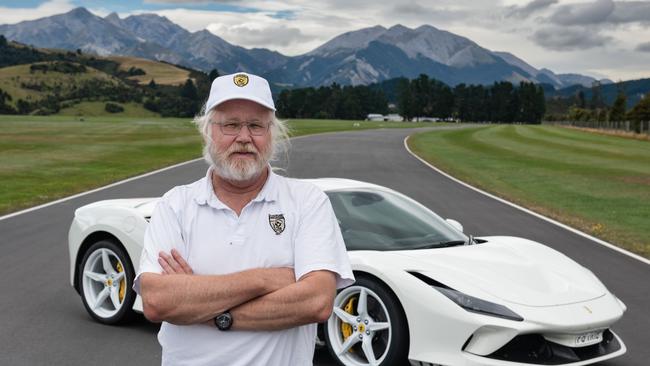

Richest 250: David Dicker’s slow road to business success picks up pace thanks to some simple business lessons

It took until the fast car enthusiast was 50 to realise what he needed to change to be a success in business – pay staff well, hire more women and stay out of the way. The results have been startling.

David Dicker was turning 50, going through a divorce, and had failed to sell his computer hardware and software company for about $10m a year or two before.

He had spent most of the 1980s designing and building his own interpretation of what a general computer should be, but had failed. It meant Dicker had to focus on distributing computers in Australia for big names such as Toshiba, Compaq and Hewlett Packard.

Yet his company, Dicker Data, had in his words “drifted”, and Dicker says he remembers being particularly conscious of coming to a time in his life when he might become irrelevant.

“The issue you have is that and no one wants to talk about it, but once you get over 50 you’re invisible to society,” he recalls in his typically blunt manner.

“So there I was, 50 years old. I was probably worth $4m or $5m. You might say wow, but I’d already been in it for 25 years so it was next to nothing. It was just complete crap. I was just fortunate I owned the company, so you’re more or less at the mercy of your own destiny and you’ve got on with it.”

Today, Dicker Data simply keeps delivering profits and dividends, year in and year out. It has become a market darling among small cap and mid cap fund managers, and has grown so valuable that it has put Dicker within reach of billionaire status thanks to his shareholding. His ex-wife Fiona Brown, who helped start the company and still sits on the board, is also on The List due to her large stake.

Dicker, now 68, got working and eventually oversaw an ASX listing for Dicker Data in January 2011 that valued the business at $25m.

Australia's Richest 250

Rinehart tops Richest 250, Canva’s Perkins the big mover

The top 10 on The List are wealthier than ever before, led by two of the country’s most successful businesswomen who have changed the face of corporate Australia.

Can restaurant king Justin Hemmes take on Melbourne?

The Sydney bar tsar reveals what his plans are for expanding his empire beyond his home turf.

How dark moments gave birth to vast Canva fortune

The Canva founders were rejected by more than 100 investors before they got their first ‘yes’.

Newcomers: The 29 wealthy debutants making their mark

Meet the little-known powerhouses, including one worth $1bn, who made The Richest 250 for the first time.

‘One service station was never going to be enough’

For Nick Andrianakos, a ‘journey of discovery to the lucky country’ has led to an estimated $894m petroleum fortune built over a lifetime.

Retail lobs into the ‘Meccaverse’

For Mecca founder Jo Horgan, there’s nothing so ‘viscerally delightful’ as going into a store and playing with products.

Tech guru Richard White’s plan to give back

WiseTech’s Richard White wants to beef up Australia’s STEM capacity. He’s setting up a new technology education foundation to get the ball rolling.

How ‘snowmobile approach’ made Bonett a billionaire

Online gift card billionaire and commercial property magnate Shaun Bonett says there are very few people who invent things. The real art is in putting things together in a better way.

Bevan Slattery kicks off his last hurrah

If Bevan Slattery’s has big plans: to pull off what will be the largest private digital infrastructure project in Australia’s history.

‘I just love anything that’s difficult’

If it sounds too good and big to be true, unstoppable property developer Lang Walker knows it’s the project for him as he loves nothing more than proving the doubters wrong.

The fortune four million parcels built

Meet the little-known powerhouse behind Australia’s burgeoning e-commerce industry.

How our billionaires relax

It’s not all work for the big players on The List: The Richest 250. They wind down in various ways, from the sporty to the leisurely – or just collecting ritzy houses.

Simple lessons in David Dicker’s 25-year overnight success

It took until the fast car enthusiast was 50 to realise what he needed to change to be a success in business – pay staff well, hire more women and stay out of the way. The results have been startling.

How Culture Kings founders made millions

Australian retail phenomenon Culture Kings is about to launch its biggest play, with its 30-something founders taking on the US market.

Gina Rinehart tops The List as NFT revolution takes off

This year’s edition of The List - Australia’s Richest 250 will show how mining and technology are now the country’s two most successful sectors.

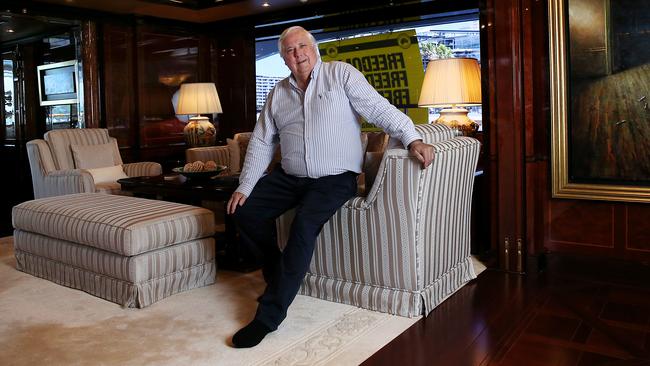

Cars and politics fuel Clive Palmer’s passion play

Clive Palmer makes more income than almost every other Australian billionaire. But how he chooses to spend it is unique.

High flyers: Private jets the new toy of choice

Forget fast cars, super yachts or luxury houses. The hottest trophy asset for Australia’s rich elite right now is a $100m jet. So who has bought one?

“My aim for the business was to be worth $50m. I would have been absolutely completely satisfied. So it is incredible now, really,” he says.

That turnaround over almost two decades is down to some simple management principles that Dicker has stuck to. He doesn’t think there is anything particularly complicated about his leadership style, though – it’s perhaps best described as keeping it as simple as possible, paying people well and staying out of the way when needs be – and at times he sounds incredulous that others make management sound so complex.

His way has eventually worked. Dicker Data is now a roughly $2.5bn company, selling and distributing technology hardware, software and cloud products for big names such as Cisco, Citrix, Dell, Lenovo, Microsoft.

It took some time for the share price to take off, but Dicker’s company has been one of the best performers on the ASX in recent years and has increased by about five times in value since 2019.

Dicker owns about 35 per cent of the company. With that comes the trappings of wealth that he now enjoys – including the road racing car business Rodin Cars that he reckons he’s sunk $40-50m into as it works on building its own line of electric sports cars.

A corporate jet is on order, and while he admits it sounds extravagant, when borders finally open Dicker will flit between Australia, Dubai and New Zealand for board meetings and company business, and attend computer conferences in the US to justify his – not the company’s – outlay.

It all sounds like a corporate leader’s dream.

Yet if Dicker were to write a management textbook explaining the secrets behind his company’s success, it would likely be a slim volume.

There are few simple themes though.

To start with, it is about persevering and sticking to what you’re capable of doing.

Dicker was no fan of school and wanted to become an apprentice sail maker but his parents wouldn’t let him. Instead, he worked in roof installation and refrigeration mechanics – “airconditioning is not exciting. I tried to get excited by it, but it’s not exciting” – and in a building business where small calculators were needed to calculate angles and lengths.

That led to using small computers, and Dicker was hooked. He travelled to America and sourced a supply of new microcomputers from a now defunct company called Vector Graphic, and had an initial aim of selling 10 computers a month in Australia.

Dicker Data now has about $2bn in annual revenue.

“A blind man could see how much potential [the industry] had, and then it was just a matter of staying in it,” he says.

Dicker Data was formed in 1978 and that stint in the 1980s when Dicker unsuccessfully tried to build his own computer followed, which also forced him to make the company strong enough to fund that project and continue after its failure. It also gave him a strong understanding of how computer systems work and how to sell the products.

“You know, if you can stay in almost anything for a long enough time you’re bound to do well,” Dicker explains. “The problem most people have is that they just chop and change all the time. They do this for three years, then they’ll go off and do that for two years and so on.”

Then there is making sure you pay your staff well, so they stay and to ensure they work hard. Dicker says the reality is that most staff work to earn money, so all he thinks of doing is making sure to pay his employees more than his competitors. That included giving every employee $1000 worth of Dicker Data shares when the company turned 40 in 2018.

“That’s how you find high-quality people, and that’s how you’re going to beat the other guy. It is such a simple thing.

“You look at professional sport. The winning teams have always almost got the highest-paid players, because they’re the best players. When you’ve got the best players you’re going to do better than others. It’s so obvious that you think people would translate that to business. But they never seem to.”

Dicker was also a pioneer in employing women, particularly mothers seeking a return to the workforce, who could set the hours that they worked around family and personal commitments. Again, he sees it as a simple yet effective way of doing business.

“We did it because we thought we’d get an advantage, not because it was a virtue-signalling thing. If you craft a policy that’s going to work then you’re going to be able to get into a decent market of people that have plenty of capability. And it just provides a much better environment all round I think.”

Many entrepreneurs running private businesses also complain about the added complexities of going public, including dealing with market regulations, investors and other financial requirements.

Dicker says that floating Dicker Data on the ASX instantly gave him better access to capital and more credibility with the banks, to an extent, and that the company was getting to a size as a private entity that its reporting requirements to the corporate regulator were substantial enough already.

Any other issues, he says, he has learnt to deal with by staying out of the way and delegating.

“It’s not that onerous, and I don’t deal with the fund managers anymore because we nearly came to blows a few times in the early days. So we decided it’d be better for Mary and Vlad [chief financial officer Mary Stojcevski and chief operating officer Vlad Mitnovetski] to do it.”

Dicker admits to some frustration though. The structure of Dicker Data’s industry means it is dominant in Australia and New Zealand, but other companies have similar distribution deals in other countries around the world.

It makes it hard to expand.

Dicker says that he was laughed at by banks when he proposed a $3bn proposal to buy US firm Tech Data six or seven years ago, despite drawing up projections that have since happened.

“Then when Ingram [Micro, a US firm] was for sale for $6bn recently, we tried again and said we could get it to the metrics we have in our company and when you did that it would all be worth $25-30bn. Again, you just can’t get the money.”

If that sounds ambitious, it pales next to Dicker’s other great passion with his Rodin Cars. He has built a 2.8km racetrack on farmland on New Zealand’s South Island, where he can race his collection of Ferraris and other fast cars.

It is also where he has poured tens of millions into top-class manufacturing facilities for what was first meant to be building the world’s fastest road racing car. It is a quest that hasn’t been without issues, as Dicker admits.

“People say to me, did you have a budget? And I just say, no, I didn’t have a budget. I just got myself into a position where I figured that no matter how much it costs to be able to pay for it, and even that got a little bit tight.

“It is relatively easy selling something but when you look at making things, that’s the real problem. You’re building something from scratch, and it’s a massive task.”

More recently, Dicker has narrowed his focus. As car makers around the world pursue Tesla in building electric vehicles, Dicker – who has amassed a collection of Ferraris and other fast cars – now wants to build an electric sports car. His theory is that while there’s plenty of demand coming for mass-market electric cars, trucks and sports utility vehicles, few are thinking about up-market fast sports versions.

“Where I am in New Zealand, I go to the supermarket on a Sunday and it’s about a 175km round trip. And I really just enjoy getting in the car and driving it. So look, maybe I’m crazy but there are 8 billion people in the world so we figure there are enough people who enjoy that sort of thing for there to be a market for it.”

Dicker is a Ferrari admirer in that the legendary Italian car maker limits annual production, and therefore drives up the demand – and price – of its product.

His ambition for the Rodin electric sports car is to eventually build demand for 50 to 100 cars annually, stick to that and resist the ambition to grow any more.

In that way, it is applying the same discipline he has in his core business, his final management lesson.

“Don’t be greedy. This is the biggest problem that people make with capitalism and the thing that they don’t understand. They think that the mantra of capitalism is to make as much as you can, whereas our capitalism mantra is, well, let’s decide what we want to make.”

“This is our target and that’s how we run Dicker Data. We work out a target for the year, break it up into monthly sub-targets, and all we want to do is get that number.

“That’s all we do. So we have a really clear focus on what the job at hand is. It’s straightforward, really.”

The 2022 edition of The List - Australia’s Richest 250 is published on Friday in The Australian.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout