Richest 250 - Bevan Slattery says HyperOne digital superhighway is his last hurrah

If Bevan Slattery’s has big plans: to pull off what will be the largest private digital infrastructure project in Australia’s history.

The List is the biggest annual study of Australia’s 250 wealthiest individuals, with final figures calculated in late February 2022. See the full list here.

Bevan Slattery is kicking off what he describes as his last hurrah. He’s building Australia’s digital superhighway, a 20,000km broadband project called HyperOne that he says will deliver tens of thousands of jobs and finally bridge the digital divide between rural and urban Australia.

Slattery’s vision for the nation may be digital but the highway that served as inspiration for the project was distinctly physical. It was a drive between Alice Springs and Darwin that sparked his billion-dollar infrastructure dream.

“There are three hours of mobile coverage black spots on that stretch of road. And if someone comes up behind you while you’re driving, in the middle of nowhere, you’re completely isolated. You can’t call anyone because you’ve got no signal,” Slattery says.

“That’s daunting, it’s confronting. For me, people need to be able to drive on our nation’s highways and feel safe, and if an accident happens or they need connectivity for whatever reason, they can get help if they need it.”

Australia's Richest 250

Rinehart tops Richest 250, Canva’s Perkins the big mover

The top 10 on The List are wealthier than ever before, led by two of the country’s most successful businesswomen who have changed the face of corporate Australia.

Can restaurant king Justin Hemmes take on Melbourne?

The Sydney bar tsar reveals what his plans are for expanding his empire beyond his home turf.

How dark moments gave birth to vast Canva fortune

The Canva founders were rejected by more than 100 investors before they got their first ‘yes’.

Newcomers: The 29 wealthy debutants making their mark

Meet the little-known powerhouses, including one worth $1bn, who made The Richest 250 for the first time.

‘One service station was never going to be enough’

For Nick Andrianakos, a ‘journey of discovery to the lucky country’ has led to an estimated $894m petroleum fortune built over a lifetime.

Retail lobs into the ‘Meccaverse’

For Mecca founder Jo Horgan, there’s nothing so ‘viscerally delightful’ as going into a store and playing with products.

Tech guru Richard White’s plan to give back

WiseTech’s Richard White wants to beef up Australia’s STEM capacity. He’s setting up a new technology education foundation to get the ball rolling.

How ‘snowmobile approach’ made Bonett a billionaire

Online gift card billionaire and commercial property magnate Shaun Bonett says there are very few people who invent things. The real art is in putting things together in a better way.

Bevan Slattery kicks off his last hurrah

If Bevan Slattery’s has big plans: to pull off what will be the largest private digital infrastructure project in Australia’s history.

‘I just love anything that’s difficult’

If it sounds too good and big to be true, unstoppable property developer Lang Walker knows it’s the project for him as he loves nothing more than proving the doubters wrong.

The fortune four million parcels built

Meet the little-known powerhouse behind Australia’s burgeoning e-commerce industry.

How our billionaires relax

It’s not all work for the big players on The List: The Richest 250. They wind down in various ways, from the sporty to the leisurely – or just collecting ritzy houses.

Simple lessons in David Dicker’s 25-year overnight success

It took until the fast car enthusiast was 50 to realise what he needed to change to be a success in business – pay staff well, hire more women and stay out of the way. The results have been startling.

How Culture Kings founders made millions

Australian retail phenomenon Culture Kings is about to launch its biggest play, with its 30-something founders taking on the US market.

Gina Rinehart tops The List as NFT revolution takes off

This year’s edition of The List - Australia’s Richest 250 will show how mining and technology are now the country’s two most successful sectors.

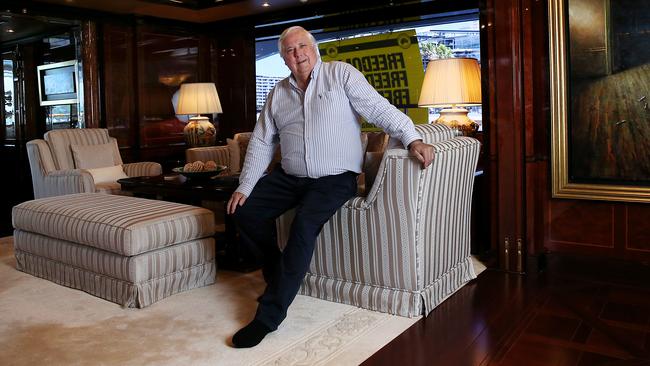

Cars and politics fuel Clive Palmer’s passion play

Clive Palmer makes more income than almost every other Australian billionaire. But how he chooses to spend it is unique.

High flyers: Private jets the new toy of choice

Forget fast cars, super yachts or luxury houses. The hottest trophy asset for Australia’s rich elite right now is a $100m jet. So who has bought one?

Slattery, 50, has packed plenty into one of the more fascinating careers in the Australian technology scene. He has started his own tech firms, and built fledgling internet service providers, data centre giants and broadband companies. All have been successful.

At a value of $1.5 billion, the private HyperOne might be his most ambitious play yet.

Slattery says HyperOne will not only be able to cover rural Australia with vital connectivity – connectivity he says will keep people safe and lead to a jobs and a financial boom for the country’s regions – but will propel Northern Australia into becoming a digital hub for Asia. He says the area’s abundant renewable energy and open space make it an ideal location to help power the world’s biggest and most demanding tech companies.

He’s taking the project deadly seriously, hiring former Queensland innovation minister Kate Jones as a key adviser, and his eyes widen when he talks excitedly about what his pet project will do for the country.

If successful, HyperOne will be the largest private digital infrastructure project in Australia’s history.

You should be able to build your business from anywhere in Australia and not have to worry about whether there’s the digital infrastructure to support it.

“In a decade’s time, I want a lot of the region’s data centres to be stored, managed and processed in Northern Australia, and that’s what’s possible here with what we’re doing,” Slattery says. “If we can achieve that, then any person who wants to start a business in regional Australia, they don’t have to worry about the digital capabilities to support it, they can just go ahead and do it.

“You should be able to build your business from anywhere in Australia and not have to worry about whether there’s the digital infrastructure to support it.

“There are half a billion people within 50 milliseconds [in ping time] of Darwin, and that is a massive opportunity for a new hub to be here.”

See The List: Australia’s Richest 250

In 2022 the internet is ubiquitous and sophisticated, but the World Wide Web was a very different place in the late 1990s, when Slattery – then a plucky young entrepreneur from Rockhampton – began making his fortune by starting technology businesses and offloading them for millions in profit. “Looking back on it now it’s pretty romantic, with its dial-up modems, the squelching sounds when you connect, and everything was so fresh and it really feels like a life-changing time,” Slattery says. “The internet was certainly more adventurous, exciting, and had a hands-on spirit. Now it’s much more of a commodity, it’s a different thing.”

Slattery says as a kid in the early 1980s he effectively acted like a human version of a file-sharing service, riding his pushbike between friends’ houses delivering copied versions of video games. He then spent his early career at the local city council, where he worked in various government departments including being in the middle of a re-do of its IT systems.

Slattery founded his first venture, iSeek, in 1998 and its technology helped families joining the internet for the first time to avoid adult content. He cashed out to US firm N2H2 in 2000 and became a millionaire at 29. He had taken his first steps towards shaping Australia’s telecommunications infrastructure for the better.

It was idle time spent at home watching Jerry Springer and NYPD Blue in that period that Slattery used to come up with PIPE Networks, a business he started with an old friend and later Shark Tank investor, Steve Baxter. In late 2001 Slattery could see broadband was on the horizon, and that data consumption would soon go through the roof.

“The exchanges at the time were all kind of community based, so the idea was to sell commercial internet exchanges around Australia. We put $50,000 in, bought awful secondhand equipment from eBay, and we said we would work four days a week and then go fishing on Fridays.”

PIPE was sold to TPG in 2010 for $373 million, and smaller Australian ISPs including iiNet and iPrimus still use its metropolitan fibre networks.

One of Slattery’s other major creations – data centre provider NEXTDC, which he founded in 2010 – now operates 11 data centres across the country and is worth nearly $5 billion.

Another Slattery-founded company, cloud connectivity provider Megaport, is now worth more than $2 billion on the ASX and yet another creation, telecommunications infrastructure provider Superloop, has a value of more than $500 million.

Succeeding as a serial founder has not been easy going, however. Two sizeable speed bumps came in the form of dual major financial crises: the dot-com crash of 2000, followed nearly a decade later by the global financial crisis.

Slattery says without a hint of irony or exaggeration that the GFC in particular nearly killed him. He was running PIPE Networks with Baxter when the most serious financial crisis since the Great Depression tore through the economy. “We lost a whole bunch of project finance, and we got through that, but I was left pretty broken,” he says. “I didn’t sleep for about three weeks for a period of time and the stress was next level. My wife said, you know, that we literally could have lost everything at that point. But we got through and I told my wife that the first decent cash exit that turns up I’m taking, because I’m never putting our family at risk like that again.

“[TPG founder] David Teoh offered a chunk of money for us to exit and I took it. And our family was secure.”

See The List: Australia’s Richest 250

The entrepreneur sees some parallels between the earlier dot-com boom and bust of 2000 and the current frothy – and highly debatable – tech company valuations of today. Amid a massive spike in adoption and use of the internet, the dot-com boom led to soaring valuations and eager investments in any company that had a dot-com suffix.The subsequent crash killed many online companies including Pets.com, Global Grossing and Webvan.

Similar questions surround today’s software companies, about whether they might survive if and when the bubble bursts.

“In the late 1990s it was all blue sky, and there was just nothing there,” Slattery says. “We’re in the hype curve now, but there’s also real substance underpinning it. There might be some issues on valuation, and of course there are some companies that when times are tough will fall over.

“But right now people are genuinely consuming digital content and applications all the time and it is a critical part of our lives. So some valuations might be frothy and it might be fair to say that there’s a bubble there and some structural challenges, and I could sit on the either side of crypto and tell you bitcoin is worth $10 or $10,000.

“But fundamentally, the digital economy is pretty solid.”

Slattery’s big-picture vision is to build digital infrastructure capable of carrying more than 10,000 terabits per second, to bolster new and emerging industries such as defence, aerospace, AI and machine learning.

Now is also the perfect time to build the network, Slattery says, because NBN construction is winding down and hundreds of skilled engineers will be looking for their next challenge.

And with the global financial crises behind him, Slattery is about to go up against what might be his toughest challenge yet: a 10,000 pound gorilla in the form of Australia’s largest telco, Telstra.

In February Telstra announced its own similarly-sized and costed national fibre network, declaring it will spend between $1.4 billion and $1.6 billion on 20,000km of new fibre to boost intercity and regional capacity.

Slattery calls Telstra’s efforts “HyperTwo”, and says of his rivals’ plan that “it was always coming”.

“What we’re focused on with ours is the innovation piece,” he says. “We’re not just building a fibre network. It’s Australia’s first 100 per cent armoured fibre network. It has triple-layer protection from termites and shovels, and we’re integrating FibreSense so that we can actually tell if someone is digging or excavating, or touching the network at all. Even if a rat is chewing on the cable we can tell before they cut it.

“The real key here is that we’re building with more than 2000 off-ramps and on-ramps in regional Australia. This network was designed from the beginning to bring as much connectivity to regional and remote Australia as far as we can, and as cost effectively as we can.

“We’ve said that if we’re going to pass a township of more than 100 people, we’re going to put an off ramp and we will work with government, we will work with wireless providers, we will work with whoever we can and service these townships across rural Australia. That’s a fundamental difference with what we’re doing.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout