This shocking life expectancy gap hasn’t shifted in a century

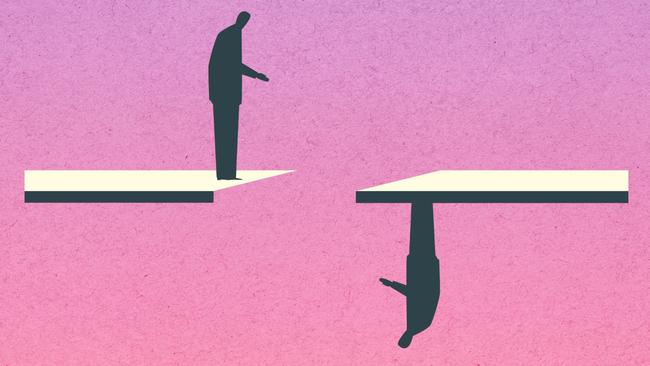

The huge gap in life expectancy between those with severe mental illness and the rest of the population is growing in Australia, with no improvement in sight.

The huge gap in life expectancy between those with severe mental illness and the rest of the population is growing in Australia, with massive disparities in physical health and alarmingly high suicide rates.

People with severe mental illness die on average 18 years earlier than the rest of the population, with life expectancy barely shifting in a century, and lagging behind many countries in Asia.

Those with severe mental illness in Australia can expect to live until the age of 65, compared with the national average of 83. The gap is around 15 years for schizophrenia. Mental illness accounts for the second-biggest burden of disease in the country next to cancer.

New mortality data obtained by professor of medicine and columnist for The Australian Steve Robson, due for imminent publication in the peer-reviewed journal the Australasian Psychiatry, lays bare the terrible plight of those with severe mental conditions.

Australian Bureau of Statistics data on causes of death for 2023 reveals huge health inequities, with extremely poor physical health outcomes and suicide and self-harm rates almost 30 times higher among those with schizophrenia.

Mental health: Cast Adrift

Home truths: jails overflow as mentally ill live on the streets

Since the closure of mental asylums, the ranks of prisoners and the homeless have swelled with the severely mentally ill.

‘Nowhere to go’: supported housing could ease the burden of mental illness

Investments in housing for those with severe mental illness would reap enormous gains and savings for the nation.

Shocking plight of mentally ill ‘a stain on nation’

Health Minister Mark Butler describes the atrocious health outcomes, social exclusion and widespread homelessness as ‘a shocking reflection on our community’. The situation is revealed in a report by The Australian and Australian National University.

The clearing out of asylums was meant to provide hope. Instead it spawned an underclass

The severely mentally ill were promised a better future after asylums were mothballed. The promises were hollow.

‘My nightmare of trauma and terror’

I am a 29-year-old woman living with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. I spent most of my younger years in and out of the public mental health system. This is my story.

Shocking life expectancy gap has not shifted in a century

The huge gap in life expectancy between those with severe mental illness and the rest of the population is growing in Australia, with no improvement in sight.

‘As a father I’m heartbroken, as a taxpayer I’m appalled’

Patrick Leunig went to a top private school and was set to study law. Then his life spiralled downwards. His grief-stricken father tells of how our system failed his son.

Freedom fight: Locked up and invisible in the heart of Australia

A young Aboriginal man’s escape from hell charts a community win for one of the many cognitively impaired and mentally troubled First Nations offenders who languish in our prison system.

Australia has a chance to fix its mental health system. Will we take it?

Australia’s broken mental health system has failed hundreds of thousands of people with severe illness with ineffective care – and that’s if they can access any at all. But one initiative may shift the dial.

‘The mental health ward became my prison cell’: a patient’s plea for change

Billie spent more than 1000 days in hospital before she turned 18. Damaged but determined, she is now speaking out for mental health reform.

The Australian, in partnership with the Australian National University, is publishing a major policy series this week on the critical neglect of severe mental illness in healthcare, housing and social services. An ANU-Australian policy report will be published on Thursday entitled Don’t Walk By: Unmet Need in Severe Chronic Mental Health Conditions.

The National Mental Health Commission recently said the nation was “seeing no improvement in the system’s ability to meet demand or prevent mental distress”, with high rates of readmission to hospital with serious mental ill-health within 28 days for those who were admitted for inpatient care. People often receive ineffective or inadequate care.

“Overall, we are not seeing improvement in mental health and wellbeing for people in Australia over the past decade or more, and some are experiencing a decline in whole of life outcomes,” the commission says in its latest national report card for 2023.

“The data clearly shows the rate of mental health concerns across our population, particularly for younger generations, is a serious national problem requiring urgent attention. Without appropriate focus on improving the determinants of mental health, including financial security, housing and loneliness, Australia’s mental health has the potential to decline even further.”

People with severe mental illness suffer extraordinarily high rates of cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes and poor metabolic health, accounting for 78 per cent of excess deaths.

When suicide rates are taken into account, the picture is even worse. Suicide is not counted as a cause of death from mental illness in national burden-of-disease reporting, but around two-thirds of those who die by suicide have a mental health condition.

When suicide is included together with the overall burden of disease attributable to mental health, psychiatric conditions are the biggest contributor to years of life lost for Australian men.

The trends are the opposite of those being recorded for almost all other diseases. Mental illness is one of the only groups in which the rate has risen over time, behind only neurological diseases.

The peak GP body’s president Michael Wright, in response to The Australian’s special series highlighting neglect of severe mental illness sufferers, said the system was failing millions. “Any GP can tell you we have an epidemic of mental health conditions in Australia,” said Dr Wright, RACGP president. “Systemic change is needed.”

There has been an average increase in funding for mental health nationwide of 2 per cent since 2017, a rate that lags well behind overall increases in health spending. There are chronic shortages of public inpatient mental health beds, and the workforce crisis is now critical, especially in the public sector. Only the most acute cases gain admission to hospital, and accessing psychiatric or psychological care outside hospital is extremely difficult and expensive. The sector is critically fragmented, especially from housing and substance abuse services.

“There’s no part of the system which is not feeling the effects of inadequate funding and workforce shortages,” said Angelo Virgona, a director of the Royal Australasian College of Psychiatrists. “There has been chronic underfunding of mental health services for a long time, particularly in the community mental health sector, despite obviously increasing demand. Huge numbers of people fall through the gaps.

“It’s a crazy system because governments do not have a plan around how they go forward with mental health service delivery,” Dr Virgona said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout