‘Nowhere to go’: supported housing could ease the burden of mental illness

As things stand, tens of thousands of people with severe mental illness cannot find – or afford – decent accommodation. Some shelter in substandard dwellings while others cluster in group homes and hostels. Many sleep rough on the streets.

Without safe and secure accommodation it is impossible to lead a healthy and fulfilling life. There is nowhere to store medications, money, or private possessions. There is no privacy and people without secure housing commonly become victims of crime. Having no address makes it impossible to communicate with government service agencies such as Centrelink.

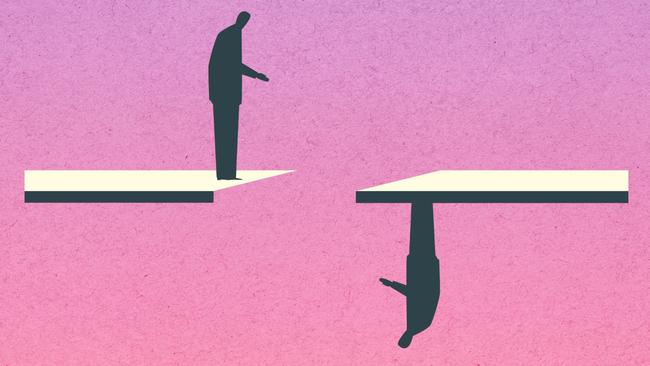

Without secure, supported housing people with severe mental illness, out of desperation, often seek succour in hospital emergency departments. They find themselves in public hospital beds or, worse, in the hell of our prisons. When, ultimately, they recover, people are discharged with nowhere to go and nobody to care for them.

Secure and supported housing is fundamental to recovery from mental illness. Without it, Australians with mental illness are condemned to ongoing ill-health, robbed of all hope. As a nation we should not accept this appalling situation.

Conditions such as schizophrenia can make it impossible to have meaningful relationships, experience happiness, complete an education, or keep a job. They lead to impoverishment and, because of the havoc and disorganisation wreaked on lives, people find themselves cast out to the fringes of society.

Most people affected by these conditions also have physical illnesses such as lung disease, diabetes and hypertension. This is, in part, due to side effects of the medications used to treat psychotic conditions. It is also a result of disordered thinking leading people to use substances such as tobacco and alcohol. Nutrition plays a role too, with affected people not being able to afford healthy food.

Dealing with all of these issues is impossible without secure housing. Supported housing reduces the need for hospital admissions and, should they occur, reduces their duration. In supported housing, Australians with severe mental illness have a much lesser need to access community services. Many can build relationships, resume education, even find meaningful jobs.

Housing models such as The Haven, Common Ground and Habilis demonstrate that supported housing is pivotal to recovery from severe mental health conditions. It is likely that more than 30,000 Australians would benefit from supported accommodation. A typical 16-person facility costs about $8m to build and, once completed, will cost about $300 daily per person to run.

Mental health: Cast Adrift

Home truths: jails overflow as mentally ill live on the streets

‘Nowhere to go’: supported housing could ease the burden of mental illness

Shocking plight of mentally ill ‘a stain on nation’

The clearing out of asylums was meant to provide hope. Instead it spawned an underclass

‘My nightmare of trauma and terror’

Shocking life expectancy gap has not shifted in a century

‘As a father I’m heartbroken, as a taxpayer I’m appalled’

Freedom fight: Locked up and invisible in the heart of Australia

Australia has a chance to fix its mental health system. Will we take it?

‘The mental health ward became my prison cell’: a patient’s plea for change

Long-term supported accommodation reduces hospital admissions by 75 per cent and, if admission is required, cuts the length of stay by 75 per cent. Australian hospitals are short more than 10,000 mental health beds.

Our study suggests that if every eligible person were in such accommodation, there would be no need for the missing hospital beds. Further, it would eliminate almost all unmet need for psychosocial care in the community. Spending of just over $5bn annually would deliver billions of dollars in savings.

Supported housing is not perfect, but it is so much better than the alternatives. If we are to have any chance of making the lives of tens of thousands of suffering Australians better, and reducing the burden on our buckling health system, then a national plan to invest in building and staffing supported housing facilities must become a national priority.

Professor Steve Robson is a surgeon and health economist. He is former president of the Australian Medical Association.

More than a quarter of a million people with chronic severe mental health conditions call Australia home. It is impossible to overestimate the profound effect these illnesses have, not only on the lives of those affected, but on their families and those who care for them. Unfortunately, as a nation, we have let many of them down badly.