This is the reality of living – and dying – with schizophrenia in Australia

Schizophrenia and related psychiatric conditions have a profound effect on people’s lives and cut lives short. People with schizophrenia have a life expectancy reduced by as much as 15 years. Few of those hospitalised are over the age of 65, because, unfortunately, most people with the illness have died by that age.

The causes of death for people with schizophrenia in 2023 are alarming evidence of healthcare outcome inequity. Loss of life due to suicide and self-harm was almost 30 times more common than for other Australians. Among the commonest causes of death for people with schizophrenia were conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and hypertension.

While these are common illnesses across our community, they caused death at rates between four and six times higher in those with schizophrenia and related illnesses, than other people. Other common causes of death were related to alcohol use and cigarette smoking. Covid-19 took the lives of people with schizophrenia at a rate about 17 times greater than for the rest of the community.

Australians with schizophrenia not only face lives blighted by stigma, isolation, and privation, they face physical health risks far above those of people without mental health problems. Close to half of all people with the condition will, at least at some stage in their lives, have substance-use problems. Half will also have serious health problems that require ongoing non-psychiatric medical care.

Unfortunately, comprehensive mental and physical health services are out of reach for many of those most severely affected by long-term severe mental health problems. Alcohol and drug services are commonly siloed, and there is a lack of co-ordination of care for different aspects of a person’s health.

Mental health: Cast Adrift

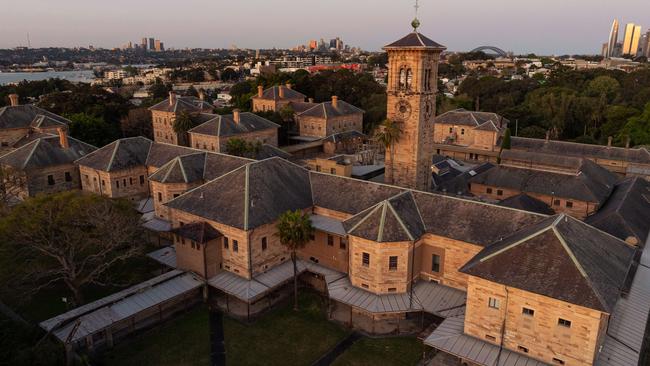

Home truths: jails overflow as mentally ill live on the streets

Since the closure of mental asylums, the ranks of prisoners and the homeless have swelled with the severely mentally ill.

‘Nowhere to go’: supported housing could ease the burden of mental illness

Investments in housing for those with severe mental illness would reap enormous gains and savings for the nation.

Shocking plight of mentally ill ‘a stain on nation’

Health Minister Mark Butler describes the atrocious health outcomes, social exclusion and widespread homelessness as ‘a shocking reflection on our community’. The situation is revealed in a report by The Australian and Australian National University.

The clearing out of asylums was meant to provide hope. Instead it spawned an underclass

The severely mentally ill were promised a better future after asylums were mothballed. The promises were hollow.

‘My nightmare of trauma and terror’

I am a 29-year-old woman living with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. I spent most of my younger years in and out of the public mental health system. This is my story.

Shocking life expectancy gap has not shifted in a century

The huge gap in life expectancy between those with severe mental illness and the rest of the population is growing in Australia, with no improvement in sight.

‘As a father I’m heartbroken, as a taxpayer I’m appalled’

Patrick Leunig went to a top private school and was set to study law. Then his life spiralled downwards. His grief-stricken father tells of how our system failed his son.

Freedom fight: Locked up and invisible in the heart of Australia

A young Aboriginal man’s escape from hell charts a community win for one of the many cognitively impaired and mentally troubled First Nations offenders who languish in our prison system.

Australia has a chance to fix its mental health system. Will we take it?

Australia’s broken mental health system has failed hundreds of thousands of people with severe illness with ineffective care – and that’s if they can access any at all. But one initiative may shift the dial.

‘The mental health ward became my prison cell’: a patient’s plea for change

Billie spent more than 1000 days in hospital before she turned 18. Damaged but determined, she is now speaking out for mental health reform.

Mental health services, in hospitals and across communities, are understaffed and under-resourced. Burnout is rife at all levels from psychiatrists and nurses to community mental health peer workers. Official estimates put the mental health workforce shortfall at well above 8000 nationally.

Effective treatment of illnesses such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and other cardiovascular diseases requires ongoing care by general practitioners and others. Yet the capacity of these services to meet community need, even for those who can afford it, are now limited.

A national report released by the government in August found that for adult Australians with chronic severe mental health conditions, more than 14 million hours of necessary psychosocial support activities were not being provided, every year.

Chronic psychotic conditions such as schizophrenia all too often leave those affected with poor education, difficulty in keeping a job, in poverty and with nowhere to live, all leading to social isolation. Effective care is more than direct medical care, and must involve psychosocial care such as: social skills training, supported employment and supported accommodation.

The move away from institutional care of people with severe long-term mental health problems means that Australia is short thousands of inpatient beds. People with severe mental illness find they have little option but to seek care through our busy emergency departments. When they recover from acute episodes of illness they are discharged from our hospitals with nowhere to go and no one to care for them.

A holistic approach to care is needed to decrease the gap in healthcare. This will require high-quality acute hospital beds and community mental healthcare linked to primary care, and alcohol and drug services. Accommodation, employment, and income support are needed. And we will need to recruit and retain a healthcare and community support workforce to deliver such services.

Steve Robson, professor of medicine at the Australian National University Medical School, and Dr Jeffrey Looi, an associate professor of psychiatry at the same medical school have co-authored a paper on this topic to be published by peer-reviewed journal Australasian Psychiatry.

The authors wish to acknowledge Lipan Rahman of the Australian Bureau of Statistics for her assistance in obtaining the data presented in this article.

IF YOU NEED SUPPORT PLEASE CONTACT:

Lifeline: 13 11 14, lifeline.org.au

SANE Support line and Forums: 1800 187 263, saneforums.org

Headspace: 1800 650 890, headspace.org.au

Beyond Blue: 1300 224 636, beyondblue.org.au

Australia is home to more than 30,000 adults living with schizophrenia, one of the most severe mental health conditions. In a medical journal editorial accepted for publication this week, based on mortality data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, we reported that there are more than one million hospital presentations for the condition every year in this country.