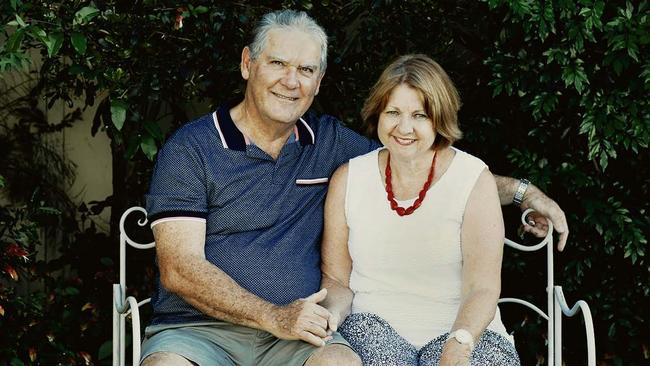

Stories from Sunny Avenue: Gary Diggles

In the finale of our six-part series we meet Gary Diggles, who has a grandstand view on Sunny Avenue – and Queensland’s murky past.

This is life as he knows it. This is Gary Diggles on a good day and good days are always the ones where you’re not dead. This is married for 48 years. This is a pet cavoodle by his feet named Dotti. This is the view from his living room window. This is a postman on a red motorcycle slipping an RACQ membership magazine inside a letterbox. This is a blue Hyundai Tucson with a Brisbane Lions bumper sticker. This is a schoolboy walking home with small white earbuds in big white ears. This is peace. This is quiet. This is looking back on it all. This is knowing how it all came to this. This is a black and yellow butterfly hovering over Sunny Avenue, Wavell Heights, at four in the afternoon, making the most of not being dead.

There are things to be learned from looking out a living room window. Weather stuff. Sky stuff. The way bricks change colour over half a century. The way shoes change, and bicycles, and the things that teenagers place in their ears. Life stuff. See that house over there? That used to be owned by the family that ran the old Chermside Dawn picture theatre on Gympie Road. Gary and his wife, Kerry, adopted a puppy from that family. That puppy, Doris, came before Daphne, who came before Dotti. See that house there? Sprawling reno. Owned by a gifted surgeon married to a gifted artist. Must be worth a bit that place. See that house there? Once home to a government MP sacked for kissing a staff member. Never a dull moment on Sunny Avenue.

There are different ways of looking at a street. What if you decided, just on a whim, to look at every flower you passed with the eyes of someone who has never seen a flower? What if you looked at a pale-headed rosella flying past with the eyes of someone who has never seen a single thing take flight? What if you chose to live your life as if you had just sprung up like a jack-in-the-box from your deathbed and skipped out of the hospital room halfway through the priest’s last rites?

Twelve years ago Gary Diggles was informed by doctors that his heart was changing shape and pushing his heart valves dangerously out of alignment. They called it a cardiomyopathy condition and they said it was terminal. Gary thought of the places he’d never seen. He thought of his wife of 48 years. He thought about how he wouldn’t live long enough to be a grandfather. But then he met a brilliant Iranian heart surgeon through Brisbane’s Prince Charles Hospital, one suburb away from Sunny Avenue, who said he could save his life by giving him a heart attack. “It’s called cardiac ablation,” Gary says. “They squirt some ethanol in through your groin, up into your heart, and they kill off a bit of heart muscle by inducing a heart attack. The heart attack happens while you’re awake on the table. It causes the offending muscle tissue to die off and when it dies the heart shrinks and all the valves fall back into alignment.” He shakes his head and raises his eyebrows. Imagine that. You wake up one morning and you put your clothes on by the bed and you take your sorry self off to surgery to have your scheduled heart attack. Gary still doesn’t understand exactly how the surgeon pulled off that last-ditch magic trick. He still doesn’t know why some people get to live through these conditions and some people don’t. He doesn’t know why he was allowed to live for 12 more years, long enough to see his grandchildren crawling across the floor of this Sunny Avenue living room like his own children did before them. He doesn’t know why he got lucky enough to be doing something so mundane and yet so miraculous as standing here at the living room window, at 70 years of age, looking out across Sunny Avenue. “All I know is I should be dead,” he says.

Gary’s been thinking about cycles lately. Climate cycles. Droughts to flooding rains. Bushfire seasons, cultural cycles. Some poor gifted joker gets plucked from obscurity and he’s feted by the world but then he says something dumb and the world claws him to near-death and then he does something unexpected and the world lifts him back up again. Australian political cycles. As far as he can tell, the Libs make it to the top and they tighten the belt and fix the budget and everybody hates them for it and then Labor makes it to the top and they loosen the belt and screw up the budget and everybody hates them for it. Rinse and repeat.

“Teacher!” That’s what Gary’s English-as-a-Second-Language students call him down at the Nundah Neighbourhood Centre. “Just call me Gary,” he tells them. Gary’s been an ESL tutor for 12 years, ever since he retired from full-time employment. He teaches migrants and refugees who’ve found themselves in suburban Brisbane having left homes in Iraq, Syria, Sudan, Somalia and almost every other corner of the world. He teaches one French guy who says he fled Paris because he couldn’t stand to live there anymore. The rage in the place. The political disharmony. And Gary wonders what’s going on in the world when people are bailing out even on that glorious City of Light.

In recent weeks he’s been teaching a group of big-hearted Bhutanese refugees who refuse to call him anything but “Teacher”. Because that’s the name he deserves. He’s teaching them things that will change their lives. Sometimes Gary wonders what he has to offer his Bhutanese students beyond the fundamentals of English. Are there other lessons he’s learned from life that he might offer them? Could he teach them more than words? Could he teach them about the suburbs of Australia? Could he teach them something about marriage? About work? About fatherhood? About making the most of not being dead?

Lesson one: how to see the world properly from your suburban living room window. Funny things used to happen from this living room window. Odd things. One night in the early 1980s Gary looked out and saw a police car slowly and repeatedly driving past his house. The police car flashed a spotlight on his house and he told Kerry how he suspected they were being watched. He wonders sometimes if he was being too dramatic, overthinking things, but these were the days of “The Joke”, the era’s notorious network of Queensland police graft and corruption, and there was always a lot for anonymous ministerial government employees to overthink about.

Gary’s job back then was as a private secretary to Queensland police minister Ron Camm and his successor, Russ Hinze. Part of his job entailed acting as a liaison – a conduit, a middleman – between the police ministers and Terry Lewis, the Queensland police commissioner who was later jailed for a decade on convictions arising from the Fitzgerald Inquiry. Anything that came from Lewis’s big office to Camm’s or Hinze’s first passed through Gary’s little office. He told Kerry he thought their phone was bugged. Every time he picked it up he’d hear a strange clicking sound and then two whirring sounds and his skin would crawl, just like his skin would crawl when he liaised with Terry Lewis.

“Why would they bug our phone?” Kerry asked.

And Gary would explain that being a liaison for Terry Lewis meant seeing and hearing things most public servants weren’t really supposed to see and hear, and there were several people who could find themselves in trouble if Gary ever spoke about those things. Gary didn’t hate Terry Lewis. He just didn’t trust the man. Something unsettling about him. Something fishy and off and nothing to joke about.

True story. One day Gary walked into his office in Brisbane’s old Treasury building and sitting on his desk was a nameless cassette tape. There were voices on this tape saying things that Gary realised were the kinds of things that would ruin careers, families, futures. He didn’t know why this tape had come to him and he spoke of it to no one except Kerry. When he looks back at this strange moment in his life he knows it for what it was. It was a test. Every now and then life asks you to make a choice between black and white when all you see is grey. That tape recording was far above his pay grade. “It was a terrible dilemma,” he says. “There was no winners in that tape coming out. I didn’t know what to do with it, so I did nothing with it, and then it disappeared.” He hid the tape in a secret place in his office.

“No one would have found it but then one day I went to get it because we were renovating that office and we were moving out temporarily. And it was gone.”

He shrugs his shoulders in the afternoon quiet of Sunny Avenue. He had neither failed nor passed the test. He never spoke of that recording again. Lesson two: know when to hold ’em, fold ’em, walk away and run. The secret to surviving.

This house is as old as Gary. Built by a family ofpainters 70 years ago. Look at the hand-cut wood palings on the outside. Look at the mitred corners of the house. They don’t build them like this anymore. He bought this house in 1974 for $27,250. It was the very limit of his budget. He was proud of himself at the age of 24 when he convinced the agent to shave $250 off the asking price. He and Kerry spent $10.50 a week on groceries back then. Gary filled his car up with petrol for $2.50. He was earning less than $200 a fortnight working in the payroll office for the Queensland Premier’s Department. Gary was the paymaster who handed employees their wages in cash from a secure bag he carried around Parliament House. On pay days he was driven to the Commonwealth Bank in Brisbane’s CBD, where he filled his bag with cash then waited outside the bank for his driver to round the block and pick him up again. One day what felt to Gary like the pointy end of a pistol was pressed hard against the base of his spine. At last, he thought, Brisbane’s criminal collective had finally clued on to the clockwork regularity of the nervy young man who exited the Commonwealth Bank each fortnight with a bag full of cold hard cash. He turned to see the end of an old woman’s walking stick. “Outta the way,” the woman said, pushing past Gary to the handrail he was obstructing. Lesson three: don’t jump to conclusions.

Lesson four: don’t be afraid of fear. Gary Diggles is not the least bit ashamed to say he was terrified of going to war. He was already working in the Premier’s Department when he received his National Service letter. He read the papers. He watched the news. He was under no illusions about the rice field hellfire he was training to run into. It’s hard for him to imagine the whole idea of that today. A young payroll officer from Windsor State School, inner-north Brisbane, is handed a gun. The son of a hardworking post office worker is handed a helmet. Gary Diggles from Brisbane, Queensland, trains for 20 months to run into some bushes in South-East Asia and kill as many people as he can. That seems absurd from the vantage point of a living room window on Sunny Avenue in 2020.

His 20 months of service felt like 20 years. He hated every second of basic training. He remembers the barking of his training officer and the spittle when he screamed, “Diggllllessss!” The endless running was hard for Gary and he had no way of knowing his gammy heart was already playing up on him. Worse than the running was the bullying. That shouty training officer made Gary and his fellow “Nashos” stand naked atop a table as officers and supposed medical staff made jokes about the size of each man’s balls. Schoolyard humiliation masked as health checks. The idea was to tear a man down and build him back up again but so often men were just torn down.

Gary walks through his Sunny Avenue home. He points at the walls, which have been renovated over time. When he first moved in those walls were covered in hard-to-remove wallpaper. Whole rooms have shifted now and the yard out back has been dug up and filled in and built over with patios and decks. There’s a framed photo on his wall of the house as it was long ago. He built a life inside this house slowly. The first bookshelf he and Kerry had in this living room was fashioned from found Besser blocks. He remembers when they were the young parents in Sunny Avenue. For years their three kids, Amy, Kate and Tom, seemed like the only kids here. Then Tracey and John Gregg moved in a few houses down. Tracey and Gary were on the street’s Safety House committee together almost 30 years ago. The Greggs had three boys and then the games of cricket started in the street and the street came to life. “Now there must be 50 kids up and down this street,” Gary says. “I’ve seen them grow from little kids to driving cars.”

Tom and Amy are solicitors now and Kate’s an interior decorator. Gary and Kerry have the regular pleasure of babysitting their children’s children. Seven grandkids in total. Today he’s babysitting Charlie and Harry, who are watching a movie in the lounge room at the back of the house. Kerry’s gone to bridge class.

‘There must be 50 kids up and down this street. I’ve seen them grow from little kids to driving cars’

Kerry’s the greatest thing that ever happened to him and he said as much in public only a few weeks ago at a party at their house. Gary got emotional because he was thinking about all the sacrifices Kerry had made for him, raising their three kids almost singlehandedly in the really heady years when he was Russ Hinze’s private secretary, a 24-7 job and then some.

Gary met Kerry when he was on rec leave from National Service. It was a blind date organised through friends. He soon asked her to marry him and he knew what he was going to do if he survived Vietnam. He would raise a family and he would be a good dad and he would tell those kids why it’s important to stand up to shouty bullies like that army training officer and then he would make grand toasts to Kerry at big house parties in the suburbs when they were old and grey. Gary had resigned himself to his tour of duty just when the Whitlam Labor Government abolished National Service and Gough Whitlam became his hero because it’s natural for a young man to admire the man he believes saved his life. Gary left the army on the day before Good Friday and he married Kerry on Easter Monday. It felt like he had a second chance at life. And it wasn’t the last time he’d feel like that.

Lessons five through seven: there are bullies in every walk of life; the politician’s pen is mightier than the sword; true love wins in the end.

Lesson eight: you never really know a man until you wash his underpants. Gary had to wash Russ Hinze’s underpants once in a small flat in New Zealand in the 1980s. Hinze had become violently ill at a ministerial conference and Gary nursed him back to health over 10 unexpected days abroad in which Hinze’s clothes needed multiple washes. In the 1970s and 1980s, Hinze served as Queensland’s Minister for Local Government (’74-’87), Minister for Racing (’80-’87), and Minister for Police (’80-’82). His knack for juggling portfolios saw him dubbed Queensland’s “Minister for Everything” in the long reign of Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen.

Rather interesting job being private secretary to Russ Hinze in the 1980s. The boss would make random and impossible requests that Gary was expected to fulfil. “I’d like to meet the Pope,” Hinze once exclaimed. “Can you organise it?” Half a year later and there’s Russell James Hinze from the Gold Coast shaking hands with Pope John Paul II in Rome.

Hinze could be a bully if you let him. Gary never let him and Hinze admired him for that. Gary visited Hinze at his home in Pimpama, on the Gold Coast, when he was close to dying from the bowel cancer that killed him in June 1991. He died before facing trial on eight counts of receiving corrupt payments of $520,000. Hinze was skin and bone that day. The ample flesh around his waist that once saw him judiciously judging Queensland beer-belly contests – Britain’s Sun newspaper once dubbed him “Supergut” – had wasted away. Hinze was all bluster in his political heyday but he was gentle and measured the last time Gary saw him. “Here was this sunken little old man,” Gary says.

“Hello, Sonno,” Hinze said. He always called Gary “Sonno”.

“Hello, Minister,” Gary said. He only ever called Hinze “Minister”.

Hinze wanted to thank Gary for something and it was a peculiar but moving kind of thank you from a frequently peculiar man who wanted to stress how grateful he was that Gary stood up to him all those times Hinze wanted to use his official ministerial expense account in questionable ways. If Gary was to summarise the exchange it would go something like this: “I’ve got myself in a spot of trouble, Sonno, but thanks for stopping me from getting into more of it.”

And Gary realised in that moment how much he was going to miss Russ Hinze being in his life. He had his flaws. He had his gifts, too. No man is black and white. It’s like that Oscar Wilde quote that’s tattooed on the forearm of the young landscape gardener, Tom Moore, who lives across the road from Gary on Sunny Avenue: “Every saint has a past and every sinner has a future.”

Some days Gary wonders if he knows more friends now who are dead than friends who are living. That’s the worst part of ageing. He can live with the back aches and the breathlessness and the forgetfulness. But all those long and horrible goodbyes and all those goodbyes you never get a chance to say, that’s the part he hates.

Lesson nine: tell your wife you love her. Tell your kids you love them. Tell your siblings. Tell your accountant. Tell your neighbour. Tell your cavoodle.

The sun is on its slow slide down over Sunny Avenue. Gary clips the dog leash around Dotti and steps out his front door and into the middle of the street. He says hello to old neighbourhood friends like Tracey Gregg and Hantun, the seasoned sailor from Burma who lives a few doors down. Tom Moore from across the road is here, too, and so are some neighbours Gary’s meeting for the first time: Hannah Scott, a mother-of-four from Manchester, England, and Robyn Clauscen, a hairdresser-cum-mum-cum-psychologist-cum-grandmother.

All these neighbours have gathered in the quiet street for a photograph because a journalist is writing a series of magazine articles about Sunny Avenue. The series is working on the notion that our streets are made up of bitumen thoroughfares and lawns and houses of wood and concrete and glass but they are also made up of stories. Our streets stay in place but our stories pass through them. Some stories thread into other stories and some stories fade away and some stories stay in place, too. The series is working on the notion there is some deeper meaning in these streets of ours. There bloody well has to be, or what the hell are we all doing here?

The photographer’s up on a ladder and the neighbours of Sunny Avenue smile because the photographer is smiling about the softness of the dusk light in this street. Click. Click. Click. And the photograph is done and the neighbours shake hands and stroll back into their homes. Gary Diggles walks Dotti back up the front stairs of his old house and he shuts his living room window because night is falling and the sun over Sunny Avenue is making way for the moon.

READ MORE: Meet the other residents from Trent Dalton’s series, The Street

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout