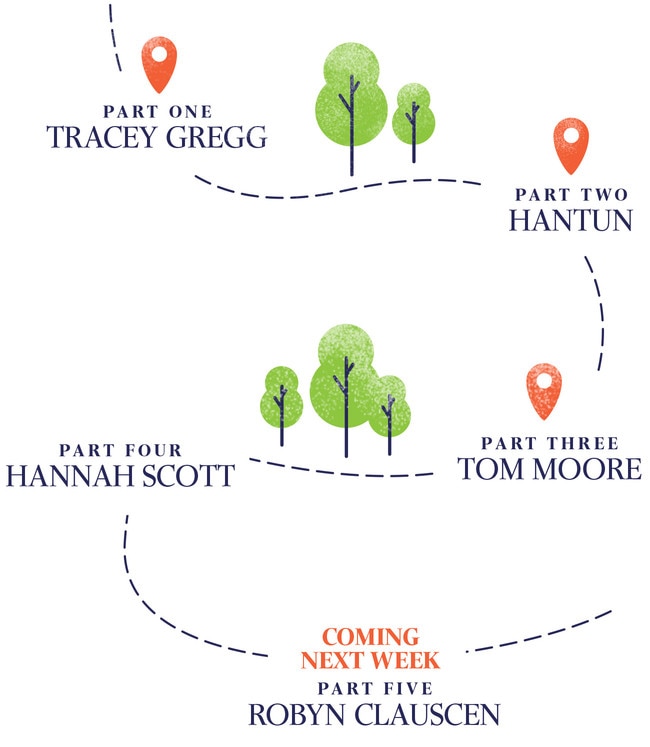

Stories from Sunny Avenue: Hannah Scott

Four kids, a new life Down Under. In the fourth of our series on Sunny Avenue, we meet Hannah Scott.

This is Hannah Scott’s new normal. For better or worse, this is how she must start her day in Sunny Avenue. A 40-year-old mother of four lying alone in bed, wide awake, waiting for the right time to call her sons into her bedroom. “OK, come on boys,” she must holler. Then her twin sons, Joel and Sam, aged eight, will run to her room and climb onto her bed and squeeze the life out of and into their mum, and then everybody’s day can begin. Most people haven’t raised twin boys living with autism spectrum disorder so they might not understand what she means when she stresses that if this simple but essential morning routine does not occur, everything that is supposed to occur afterwards will disintegrate. She can’t go to the boys. They must come to her. The boys can’t wake to find her already buzzing about in the kitchen. They must find her in her bedroom. That’s just how it is. Don’t make her explain it. Please don’t make her unpack the complexities of ASD and exactly how many hours of her life she has laid back on her bed asking herself if she’s making all the right moves. Just let her go make breakfast in peace.

When she’s driving in heavy traffic, Hannah always thinks about how she beeps her horn. Too long? Too aggressive? She is acutely aware that every person driving on the roads between Sunny Avenue, Wavell Heights, and the Brisbane CBD – every person driving in the world, in fact – has a backstory that might give some account for their apparent lack of concentration or consideration. Some drivers’ backstories are too tragic for words and some are blessed with nothing but good fortune and gold jewellery. But if someone has cut her off or if someone is merging into traffic with all the grace of a charging stegosaurus, Hannah tries to remember the times when she’s been beeped by some angry bloke in a sports car and she’s wanted to sit that bloke down for a good half-hour to tell him that the reason she was a bit slow to notice the green light was because she was thinking about whether her eldest daughter, Leila, 12, was coping with leaving all her friends behind in Manchester, England, since the family moved to Brisbane, Australia, in August 2018. She was thinking about how an essay for her university course was due in a week’s time and she hadn’t started it because her week was spent helping Leila and her younger sister, Polly, 10, with their homework and attending specialist appointments with Joel and Sam and grocery shopping and long-distance phone calls to her mum and dad in England and cooking dinner and having the airconditioning unit fixed and cleaning the house and taking the girls to band practice.

She was thinking about how long a woman born and bred in Manchester could expect to live through a summer this hot in a land so strange and volatile that it sets itself on fire and burns so hard and strong and long that it swallows up the sky. She was thinking about making all the right moves. She was thinking about what her parents said to her when she told them she was shifting the family to Australia. They said she would turn into a “redneck” within three months, and Hannah was offended by that. She wondered how such a narrow-minded thought could come from such big-hearted and open-minded parents who were proven wrong because within three months of moving here Hannah realised that only the worst things that ever happen in Australia make the news in England and what never makes the news is the absolutely ordinary miracle that is the gently bubbling melting pot of neighbourhood kindness and harmony and colour that exists in Sunny Avenue. But when some bloke in a sports car beeps loudly and screams at her in traffic for taking a moment to notice that the lights have turned green, Hannah Scott wonders if there are parts of the melting pot her British soup spoon just hasn’t scooped up yet.

Kevin is the Scott family’s English bulldog whose normally statesmanlike, Churchillian demeanour turns to water with a belly rub. In the kitchen after breakfast he rests his paws on Leila’s thighs and she gives him a deep scratch and he nods his head in giddy appreciation. Leila’s decided this morning that she wants to be a vet when she grows up.

“You know it’s not just dogs vets work with?” Hannah says. Leila seems puzzled. “What if someone comes into your surgery with a spider?” Leila reels back in horror.

It was Hannah’s husband, Trent, who wanted to move the family to his home country in 2018. Leila and Polly were reluctant to leave their friends but their dad’s promise of a bigger yard in Australia – one big enough for a big cuddly dog like Kevin – helped cushion the blow of new beginnings. Leila thinks she’s no good at making new friends and she’s nervous about starting her first year of high school at Wavell State High School, only four streets from their house. She wishes she was more like Polly, who makes friends easily because she sees the very best in everyone.

But Leila’s not the only one struggling to make friends. Hannah just turned 40 and she’s been wondering lately why she hasn’t opened her big heart and big mind up to new friendships here in Sunny Avenue like she did with strangers in her 20s and 30s. There were friendships she flew away from in Manchester that were forged over half a lifetime. There are friends she’d die for back in England. One of those is Helen, who made the handmade wooden sign on the dining room wall that reads: “Hannah is perfect in all ways.” Helen made that sign because she knows that Hannah too often focuses on her failings as a mum/wife/daughter/sister/friend and not her many successes. Helen knew there would be no one like her in Australia to tell Hannah to stop being silly and maybe this sign could act as a daily reminder of how Helen has always seen her.

“How do I make friends like that again after all this time?” she asks herself. “It’s a lot easier to do a move like this when you’re young.” She shrugs her shoulders, sighs. “I just feel slightly secluded here.”

Hannah was playing tennis with Helen almost 15 years ago when she first laid eyes on Trent, who was playing club cricket on an oval adjacent to their tennis court. It was Helen who checked him out first in the outfield but it was Hannah who spoke to him first that afternoon in the sports club bar. “What’s your name?” Hannah asked.

“Trent,” said her future husband.

Hannah had never heard the name in all her years in England.

“What’s your real name?” she said.

“Trent,” he said.

“Trent? That’s not a name.”

“Loads of Trents in Australia,” Trent said.

They were together for two weeks before Trent had to return to Australia. But they were in love and they made it work through long distance phone calls until he could find his way back to England. Trent stayed for another 12 years until he turned to his wife and said, “I can’t do this anymore”. He was talking about the weather. He couldn’t cope with staying inside for one more English winter. “But now we’re stuck inside today in Sunny Avenue because it’s too bloody hot!” Hannah laughs.

She loved giving birth. The whole wild bit. Someone asked her the other day if she would consider having another baby if the hands on her biological clock weren’t so close to midnight. She thought about when she was 27 and she was so worried about the hour hands winding around too fast on that clock and how, nowadays, she sees plenty of mums giving birth upwards of 40. She said she’d happily have another baby and feel that unparalleled euphoria of bringing life into this strange spinning planet but she just wouldn’t be able to bring that baby home and raise it. No room. Not enough spare cash. Too many essays due in next week. Too bloody hot.

Sometimes Leila and Polly see a very famous British man on television who their mum once knew very well. “He’s on TV again, Mum,” the girls call from the living room. And Hannah emerges reluctantly from the kitchen and looks at the television and smiles and shakes her head at the wild interest the girls are taking in this handsome and rich man – a millionaire and then some – whose name she will not say in public out of respect for his privacy. This man was once her fiance. They were together for eight years and engaged to be married when Hannah ended the relationship. What she sees when she sees that man on television is an alternative life; a vague and grey road she might once have walked down to a place she could not see clearly but a place she realised she didn’t want to go.

“It was heartbreaking for both of us,” she says. “It took a lot of getting over.” It was embarrassing, too, going so far down a road and then having to tell family and friends that she wanted to turn back. It wasn’t the right road. “It’s really difficult to describe because he was, on paper, everything you could possibly wish for, but I suppose that just taught me that I have to go with my gut about things.”

It takes courage to pull out of something like that. Better to suffer a year of awkward conversations than to spend 50 years ignoring the truth gently tapping on the back door of her heart. “Yeah,” she smiles, raising her eyebrows. “People are still like, ‘Why would you give that up? Why would you?’” But that was one of the best life lessons she could give her girls. Follow your heart, always. Follow your truth.

If Hannah was to be completely truthful about her life right now she would say this particular phase hasn’t been the easiest. It’s been a peculiar and transitional time. Sunny Avenue is so very different to Manchester. The houses are different. The streets are different. She goes into seafood shops to order a “chip butty” and the young people behind the counter look at her strangely.

She was born in Eccles, Greater Manchester, and raised in a large three-level Victorian home with Jane Austen staircases, Beatrix Potter gardens and a cellar. Snowy winters. Golden summers. She has two older brothers, Ben and Rod. Her parents are named Elizabeth and Phillip. Eccles’ own Queen Betty and Prince Phillip. Her father was the principal at a local primary school. He rode to work and the family ate every dinner at the dining table. Hannah’s parents were 24-7 doers. Always doing things in the community. Always doing things in their street. They’re retired now and devote most of their time to a local charity food bank. They have big bleeding hearts like Hannah’s Sunny Avenue neighbour, Tracey Gregg, who volunteers at charity food banks across Brisbane.

Sometimes her older brothers send her a text from Manchester with a photograph of themselves having fun with their mum and dad in the family home and the photo always makes Hannah smile as much as it makes her heart hurt.

She loved her childhood but if there’s one question mark she has over her mum and dad’s parenting style it’s the long leash they gave their kids. “Just be back before dark,” they said. Beyond that, Hannah’s choices were, for better or worse, her own. In 2020, that seems to Hannah like a remarkable amount of freedom to give a child. Some days Leila and Polly walk 100m to the bakery in the next street and she can’t relax until they return. She hates that she’s like that and she doesn’t know where that comes from. “My parents were really good fun and they were very liberal parents but that made us want to spend time with them more,” she says.

Hannah wonders sometimes if she’s too hard on her kids, but they still want to spend time with her and that seems as good a barometer as any as to how she’s doing as a mother. She asks her daughters now across the kitchen table: “You two like to spend time with me still, don’t you?”

“Of course we do, Mum,” Leila beams and Hannah beams with her.

She’s been trying to keep the girls off mobile phones. “I see what it does to them and I don’t like it,” she says. “My strategy is I like to be fun to be around so they don’t even want to be on the phone.”

Hannah’s been negotiating mobile phone rules with Leila. Here’s how it’s gonna work. Leila can have a phone but she does not own the phone. She can take a phone when she goes to tennis practice but then she needs to hand it back. Time limits on phone usage in the house. TikTok is banned. The girls used to go off on their own and watch dance clips on the video sharing app and dance along, and that all seemed fine enough until Trent passed them one day while they were watching a video featuring the kind of swearing that would be considered inappropriate even on some of his worksites. “Stop!” Trent said immediately. And that was the end of TikTok. Hannah’s noticed the girls haven’t been going off on their own as much as they once did. “You weren’t part of the family for a few weeks there, were you?” she says to Leila. “Yeah, we were sitting in our room and just dancing and posting weird videos,” Leila shrugs.

Hannah was a teacher in England before moving to Australia and she’s seen the very best and the very worst of pre-teen behaviour, enough for her to know that Leila will grow into a bright and strong woman who will make a lot more right moves than wrong ones.

Hannah was a high school languages teacher. “Mum knows basically every language in the world,” Leila says. French, German, Spanish and Italian, mostly. When she moved to Australia she was told her teaching qualifications did not translate to the Australian education system. She would need to study again for a teaching degree if she wanted to work. She was hurt by this. Insulted, at first. She’s a fine teacher. Tireless and tenacious. In England, she taught the tough kids in the tough schools. She always asked for the trouble schools. Working class, at-risk, high drama. She watched some of those kids in her charge go on to be accepted into Oxford and Cambridge universities. “So why am I not good enough to teach here?” she asked herself. But she got it. There were different ways of learning.

“It’s nearly killed me, studying with the four kids,” she says. “But I really want to do it.” Her parents said she was mad to study all over again and she wasn’t going to bother but then she took Leila to an open day at a local state school and she saw the way a teacher was interacting with her students and she was reminded that teaching was what she was, as far as she can tell, put on this Earth to do, much like her father before her.

Trent is a tiler. It’s a tough job. Very early morningsand very hard work. Everybody likes the big, heavy tiles these days. Bend at the knees, lift a 20kg tile on your forearms, bend at the knees, lay the tile, repeat 200 times. Trent’s normally wringing the sweat from his T-shirt by 9am. But he doesn’t complain. He lifts all those tiles for Hannah and the kids. Simple as that. That’s the deal. No big deal.

Hannah loves Trent so deeply that when she’s asked to take her time for one full minute and really think about what he means to her, she starts to cry. She weeps right here at her kitchen table beneath four framed school photographs of her children. “He makes me feel safe,” she says.

She feels for Trent sometimes because she knows there are times when he’d like to go out into the street on Sunny Avenue with his boys and play cricket or go into the backyard with them to kick a footy but Joel and Sam just aren’t those kind of boys. “They won’t ride bikes,” Hannah says. “They won’t play cricket with their dad over summer. They just have a tunnel vision about those types of things.”

The boys are playing in the lounge room with two soft toys, Paddington Bear and a scruffy red fox named Nick Wilde.

“He’s from Zootopia,” Sam says.

“We’re from England and in England we call it Zootropolis,” says Joel.

The television is turned off in the living room.

“Do you like TV?” Sam asks.

The boys ask people this question, Hannah explains, because they are terrified of television. Trent and Hannah struggled to convince the boys to board the plane to Australia because they were terrified of the screens built into every seat-back playing all manner of unpredictable programs. There is a small and very specific list of shows they can watch but most TV programs will raise significant there-goes-the-afternoon emotional and behavioural issues for the boys.

Hannah smiles. That’s just how it is. She’s staggered by and deeply grateful for the level of ASD-related support she’s found in the Australian education system. “Huge support from the teachers and the kids as well,” she says. “We didn’t get that in England.”

She shrugs her shoulders now. She reels from any sense of feeling sorry for herself; shakes her head as she shakes it from her system. She looks out the front windows of her living room. “Everything’s relative, isn’t it?” she says. She points at the houses across the street. “I don’t know what’s going on for them in their lives. We can pass each other in the street and nod hello, but I don’t know what they’re going through. Everyone’s got their own little crosses to bear, don’t they?” And everybody’s got their own ways of bearing them.

There’s a framed photograph in the corner of Hannah’s kitchen. People often ask her why she has it in the kitchen because it’s not a pretty photograph, not the warmest image one could see over a plate of pancakes and maple syrup. It’s a shot of Joel in hospital as a baby recovering from open-heart surgery. His heart failed at two weeks old and he was rushed to emergency and he somehow survived when all the odds in the world said he would not. The very worst and then the best time of Hannah’s life. Both ends of emotion in a single photograph.

Leila’s by her side as she stares at that image in the corner of the kitchen. “After getting through that, everything changed,” Hannah says. “Right. OK. Whatever happens now, I can take it. I’ve got that mentality now. I don’t think I was that strong before, mentally. I still find things tough and I cry.”

Hannah smiles at Leila.

“I cry a lot,” Hannah admits.

Leila smiles too. “Yeah, you do.”

Hannah laughs.

“But then I pick myself up and I just go, ‘No, I can do this’. And I keep this picture of him here because it makes me feel…” She can’t find the right word. “I imagine it would be weird to see for some people but it’s like, ‘Remember Hannah, how strong you were? Remember that?’”

That photograph has become a kind of magic. It’s transformative. One look and she feels better because she remembers that there was a time in her life when all she wished for and all she needed in this world was Joel’s steady heartbeat. And here’s Joel now, running after his twin brother through the kitchen of her house in Sunny Avenue and Nick Wilde the red fox seems hungry and the days seem numbered for poor old Paddington Bear.

-

Next week: Robyn Clauscen’s story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout