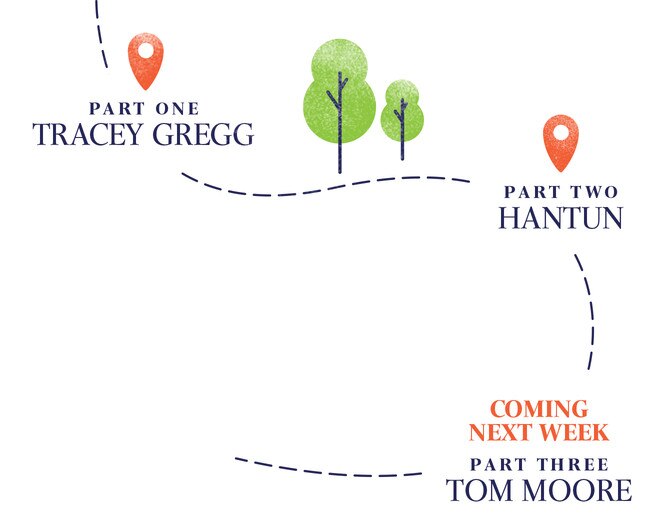

Stories from Sunny Avenue: Hantun Hantun

Love, death, hope, struggle… the stories of the residents of Sunny Avenue tell the story of Australia. In the second part of our series based on one Brisbane street, we meet Hantun Hantun.

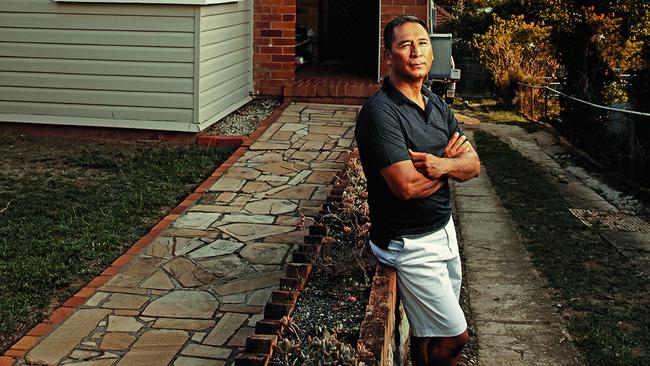

His name is an echo. Hantun Hantun. Last name same as the first. His name is like every good thing he’s ever taken from Buddhism. Everything you say comes back to you. Everything you do comes back to you. Hantun Hantun starts his day at 4am with a question of how he will choose to be in front of the bathroom mirror. He’s 56 years old and he only recently remembered a lesson he learnt long ago: that he could control the man staring back at him. There are bags under that man’s eyes. There are old burn scars across his arms and legs. He could choose to make that man in the mirror frown. He could choose to make him weep. He could choose to make him grit his teeth and flare his nostrils and curse himself for ever chasing true love to the continent of Australia. But this morning, like yesterday morning, he makes the man in the mirror smile. Then he turns off the bathroom light.

He eats breakfast alone. Burmese rice noodle soup. Steamed beans. He leaves Sunny Avenue before dawn and his work truck breaks the suburban silence of Wavell Heights, north Brisbane, as it finds second gear and his smartphone map finds its way to a job in The Gap in the city’s inner west. Hantun’s the sole operator of Kwik Kerb Chermside, under the global Kwik Kerb brand. Business has been slow lately. Too little rain for too long. No rain means no pretty gardens. No pretty gardens means no reason to hire him to build a pretty concrete edge for a pretty garden. No new edges means no extra money means no extra work-hands means longer days working in the baking Queensland sun by himself pushing wheelbarrow loads of wet concrete.

He’s spent by 2pm. His lower back aches, his fingers are seizing up and he wants to finish for the day. Then his phone buzzes with a text message from his eldest daughter, Thida, who tells her father she loves him and thanks him for everything he’s done for her. She tells him this because he taught her long ago that everything you say comes back to you. Hantun Hantun puts the phone down in a shady spot by the garden edge and he works without a water break for two more hours, not even realising that his back has stopped aching.

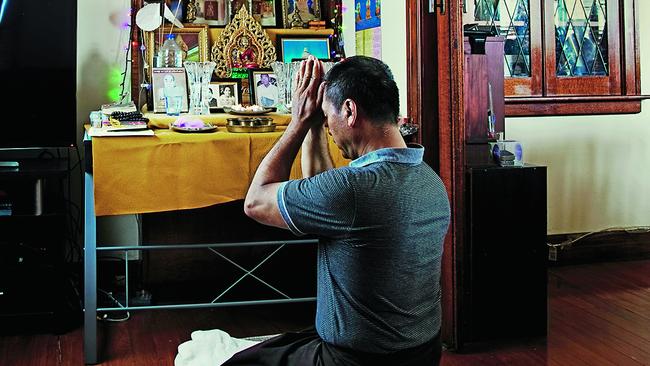

“U” in Burmese is like “Mr”. “Daw” in Burmese is like “Mrs”. A framed black and white photograph of Hantun’s mother, Daw Khin Than, and his father, U Tin Win, hangs on his living room wall above the Buddhist shrine where he prays every morning and night. Hantun was born in Burma – he only ever calls his homeland Burma, eschewing its modern name, Myanmar – in 1963, one year after the country was consumed by a brutal military rule that lasted half a century. He was born with the name Han Tun. There are no traditional family surnames where he grew up. The name Hantun Hantun was the one he gave himself many years later in order to settle in Australia, a land where surnames are needed.

“You can achieve anything you want to in Burma, son,” his father told him when he was a boy. “Just don’t talk about politics. You are free to go anywhere, son. Just don’t go anywhere near politics.” His parents ran a laundry business in the capital, Rangoon (now Yangon). His father was an honest man who told his only son the secret purpose of every man’s existence. The very meaning of life, he said, was to keep one’s family together through endless work. Service to family above all else. A simple and honourable expectation from God and the universe.

Every coin, every Burmese kyat U Tin Win ever made was handed over to his wife. In turn, every coin Hantun made went to his mother, who ran the household finances. Every coin made by his older sister, Khin Win Oo, and his younger sister, Aye Aye Khaing, went to their mother too. The family ate together. They laughed together. They stayed together. When Hantun was 15 his father left the running of the laundry business to his son and turned to selling used cars and jewellery. Every coin U Tin Win made selling old sedans and older rubies was handed to his wife. Marriage, his father said, was the sacred and unbreakable foundation from which a family prospered.

“I trust you, son,” he said. And then his greatest words of wisdom: “You are allowed to be silly sometimes. You are never allowed to be stupid.”

Being silly meant being free, being bold, having the courage to back yourself when everybody said you were wrong. Being stupid was backing yourself when you knew for a fact you were wrong. Stupid, his father said, was Hantun joining friends at the pro-democracy protests following the nationwide uprising on August 8, 1988 in which thousands – monks, housewives, students, doctors and common workers – were killed by the military. These friends of Hantun’s were at university, but he wasn’t. “Your friends know what they’re fighting for,” his father said. “But you’re just there to be with your friends. You don’t even know what you’re protesting. Your friends will die for a reason. If you know nothing, you die for nothing.”

Don’t smoke, his father said. Don’t gamble. Don’t drink. Don’t start fights. Rangoon is a dangerous place, his father said. Run when you can from a fight. If you can’t run, son, then fight like a dog because I love you and your mum loves you and somebody’s got to run the laundry.

In his teens, Hantun had a karate coach who told him the toughest fights he would face in life would not be fought with his fists. They would be battles of heart and head and the real enemy would look exactly like Hantun. Martial arts, his sensei said, is not about fighting. It’s about surviving. And surviving is an art carried out from the inside. Sensei U Thaung Din was a wise man known as “the father of karate” in Burma and Hantun was wise enough, too, to know his sensei was referring to the young man who stared back at him every morning in the bathroom mirror. Life is a mirror. Life is a man staring back at you and you must decide how you will stare back at him.

Hantun’s neighbour has a dog that barks whenever guests come to Hantun’s house. The dog sits at the side fence and barks non-stop at the open window by the dining table where Hantun eats with his guests. “He won’t stop until you’ve gone,” he says. He smiles and shrugs. He grew up amid one of the world’s longest civil wars, a connected series of ethnic conflicts across his homeland marked by mass forced displacement, starvation, slavery, torture and genocide. He can cope with a dog barking in Sunny Avenue, Wavell Heights.

A white delivery van pulls up outside and Hantun signs for and collects a parcel from a young man in an orange polo. His neighbour across the road, Tracey Gregg, is unloading groceries from the back of her car. She closes her garage door and switches a grocery bag from her right fist to her left, which already carries a bag, so she can wave at her neighbour. “Hello Hantun!” she calls. “Hello Tracey,” Hantun replies, beaming.

Hantun adores Tracey. She’s everything he loves about Australia. She is openness. She is kindness. Everything she does comes back to her. Hantun has been in Sunny Avenue for 11 years and has watched, from afar, Tracey’s three sons grow into good men who always visit their mum and wrap their arms around her like they know deep down who was responsible for their joy. He has watched them move out to travel the world, hunt down their dreams. He remembers being their age and hugging his mother that way.

Burmese sons can’t dream as big as the sons of Sunny Avenue. That is a simple fact of life and geography, he says. Hantun remembers there being only two realistic options available to him once he left high school: work for the government or start a small business. He borrowed money from his uncle to start a VCR and television rental business and every coin he made he gave to his mum. In 1989, he followed a friend’s advice and flew to Bangkok to board a Japanese cargo ship. He wanted to see the world and that rusting ship took him to three-quarters of it. He sailed to the edge of the Far East and across the Pacific. China. Japan. Cambodia. Christmas Island. Korea. Singapore. Hong Kong. All the way to the edge of Russia. An industrious deckhand travelling the world, collecting tales to one day tell his three children before lights out.

Most nights he slept as few as three hours because he was combining his cleaning duties with lessons in navigation. Wash the decks from 4am to 8am. Breakfast and nap. Scrub the toilets from 1pm to 3pm. One hour break. More cleaning from 4pm to 8pm. Navigation lessons from 8pm to midnight.

When he placed his head back down on a welcoming pillow each night he thought of his family. He was 24 and had never had a girlfriend. He sailed the high seas for four-and-a-half years and every penny he made went back to his family. The thought of providing for his family, he realised, filled him with a profound energy. He did not need the sleep the other cadets seemed to need. He did not smoke. He did not drink. He received a beer ration like every other man on the ship and he stocked his beers up beneath his bed and sold them for a high price to the thirsty old sailing salts whose beer rations lasted about as long as a lightning strike in a South China Sea typhoon. That money, too, went back to his mother.

During those raging typhoons Hantun walked out on to the slippery deck to complete his duties. Tying things down. Shutting things up. The storm would smash his face and the waves would crash over the deck and he would stare into the dark ocean and think of his mother. “I will die for you mother,” he whispered to himself. “And I will be proud to die working for our family.”

One day on deck an inexperienced ship’s bosun had filled a portable lamp with gas and was trying to light it when he asked a passing Hantun why he couldn’t get it to work. Hantun had just put his fingers on a loose screw when the lamp suddenly exploded in a ball of flame and Hantun realised the bosun had filled it with the wrong kind of gas. He was lucky that day because it was the middle of winter in Japan and he was wearing three coats to keep himself warm on deck. His top coat was set on fire; he slipped it off immediately and threw it in the water and, instinctively, ran for the nearest fire extinguisher. As he ran across the deck, a group of Japanese sailors pointed at Hantun, screaming, ‘Fire, fire, fire!’ “I know,” screamed Hantun. “That’s why I’m getting the fire extinguisher.”

“No,” yelled the sailors, pointing at Hantun’s legs. “You are on fire!” Hantun looked down and saw flames rising from his feet to his thighs. He fell to the ground and ripped his trousers off, taking thick layers of skin with them. He was hospitalised for a month in South Korea. The pain went away; the scars did not. But he gets to decide how he looks at those scars. He decides every day to see them as a sign of his good fortune. A sign of his survival.

Hantun is weeping now at his dining table. The neighbour’s dog is not barking. It lost its voice after three hours. Hantun’s trying to explain how true love was tied to his greatest regret. His greatest failure. If he was to go back and really think about what brought him here to Sunny Avenue, there are two moments that stick out clearly in his mind. The first was in Singapore some months after the accident with the lamp. He had risen to the rank of second mate and was working on a series of small ships based in the Port of Singapore. He was about to head home to his family in Burma when a workmate asked if he would like to join a small crew sailing to Melbourne, Australia. Simple job. Quick and lucrative. Pick up a ship in the dry dock of Port Melbourne and sail it back to Singapore.

“No,” Hantun said. “I need to go home to see my family.”

“But we need you!” the crewmate begged.

Hantun shakes his head. “My whole life would have been different if I did not take that job.”

That quick trip turned into a three-month wait in the hot and strange continent of Australia as the pick-up ship was readied for sea. In Port Melbourne, the small crew was visited by a priest from St Augustine’s Church in the city. Accompanying him was an Australian woman – a church volunteer – who was part of the second moment that changed Hantun’s life irrevocably. That second moment was the first kiss they shared on a romantic trip to Boracay Island in the Philippines. He was in love and that first kiss came when he was 29 years old. Her name was Karen. They wed in the Victorian Marriage Registry, then married again six months later in a traditional ceremony in Burma before Hantun’s mother and father and sisters.

They settled in Melbourne and Hantun found a steady job at the GM-Holden manufacturing plant at Port Melbourne. He worked there for eight years. Thida was born in 1996, Thomas arrived two years later and another daughter, Hillary, was born two years after that. Hantun looks up at the framed family portrait above his wide-screen television. A single father and his three grown-up kids. He’s so proud of those kids. The divorce was messy. Ugly, too, but it never stopped those kids from achieving their dreams.

Trying to pinpoint where love goes wrong is a tougher task than pinpointing where it goes right. He thought it would be so simple: he would work hard and, like his father before him, he would pass on every cent to his wife and she would be happy. But relationships here in Australia seemed different to how they were in Burma. More complex.

Not long ago Thida brought a boyfriend to Hantun’s house. They were talking over dinner about the notion of true love. Hantun had much to say about the complexities of true love but he kept quiet. As the conversation went on, he thought back on what he calls “the rot” that set in to his marriage long ago. She wanted to move to Queensland to be closer to her family. Hantun took a redundancy from Holden and the family moved to Queensland and Hantun took a job driving for Yellow Cabs. But the arguments did not end. They were simply out of synch, he realised. They were not meant to be together. True love, Hantun realised too slowly, was so much more than a kiss on a moonlit beach. “I want a divorce,” Karen said and the words were shocking to him, even though he’d seen them coming years before.

As Thida and her boyfriend spoke of love and relationships that night over dinner, Hantun thought of his own mum and dad. In 2006, his sister called to say he had to come to Burma immediately because their mother was gravely ill. She was dying. He told his sister he couldn’t because he was midway through divorce proceedings. He told her not to tell their parents. Such news would bring great shame to his mother.

“In Burma you do not get divorced, you find solution,” Hantun explains. “Only in the worst cases of marriage do you get divorced. In my family, nobody was ever divorced. I didn’t want my mum to know this stuff. My dad has health condition, too. News like that would kill him.”

Once things were sorted out, Hantun immediately flew to Burma. “But, too late,” he says. “Mum’s gone.” After several days of silence his father opened up: “Do you know your mother kept calling your name until her last breath?”

“Nobody knew I couldn’t come because my world was falling apart,” Hantun says. “I didn’t know what to say.” He couldn’t tell his father he had failed to keep his own family together.

Two years later, Hantun’s father was in a critical condition. Hantun flew back to be by his side and before he entered the hospital, a close family friend said: “It’s time to tell your father the truth about why you couldn’t be there for your mother.”

“I will,” vowed Hantun.

But at the hospital he found his father in a state of confusion. His memory was failing. “Are you a friend of my son’s?” he asked, bewildered.

“I am your son,” Hantun said.

He stayed by his father’s side for four weeks. He simply told him that he loved him. He never told him about the divorce.

That night around the dinner table when Thida and her boyfriend were talking about love and relationships and the future, Hantun had only two pieces of advice for his daughter. “True love is understanding,” he told her. “And true love is forgiving.” Then he took the plates to the kitchen and rinsed them off in the sink.

Hantun sometimes looks at himself in the bathroom mirror wondering what it was about him that his wife fell out of love with. His kids now want their father to start dating again. He tells them he won’t meet another woman. He doesn’t trust that kind of love anymore. But he has another kind of love, and he has enough of it to last two more lifetimes. It’s all the love he has for Thida, Thomas and Hillary. “I don’t need any more love,” he tells them.

But then he wonders if that’s just something men tell themselves when they’re scared. He thinks for a long moment at his kitchen table. “I’m afraid of falling in love again,” he says softly.

He sometimes wonders if love is a gift that comes, like anything else in life, with a time limit. Why do some children with good hearts only get to live for 10 years while some men with bad hearts get to live to 100? Why wouldn’t love come with the same warped and arbitrary time restrictions? He got almost 10 good years of love with his ex-wife. If that’s all he was supposed to have of love, if that was his designated allotment, that’s fine by him.

What is it with us humans, he wonders. “We always want more.” More space, more things, more joy, more peace, more quiet, more bandwidth, more milk, more love. “More” is a mechanical hare circling forever around a greyhound racing track, and it is rigged to never be caught. “More” is all those suns he saw falling into the South China Sea. No matter how many ships he sailed toward it he could never catch it before it melted away.

So now he enjoys the sun while it lasts. If it burns his back when he’s bent over working wet concrete into garden edging, so be it. He will finish the job and he’ll clean up the job site so it looks like he was never there and then he will drive back home to Sunny Avenue and he will take his shoes off before he steps inside the house. He will look at a framed certificate on his living room wall, the one that confirms he wasn’t dreaming and Thida really did graduate from the University of Queensland with a Bachelor of Speech Pathology (Honours), and he will know that every prayer he ever uttered before bed has come back to him. Everything you say comes back to you. Everything you do comes back.

Hantun Hantun will have his dinner. He will watch a little television. He will shower and before bed he will find the man staring back at him in the bathroom mirror. He will choose to smile at that man and then he will lie alone on his bed and then he will reach for a bedside lamp and then another light will go out on Sunny Avenue.

Next week: Tom Moore’s story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout