Stories from Sunny Avenue, Wavell Heights, Brisbane: Tom Moore

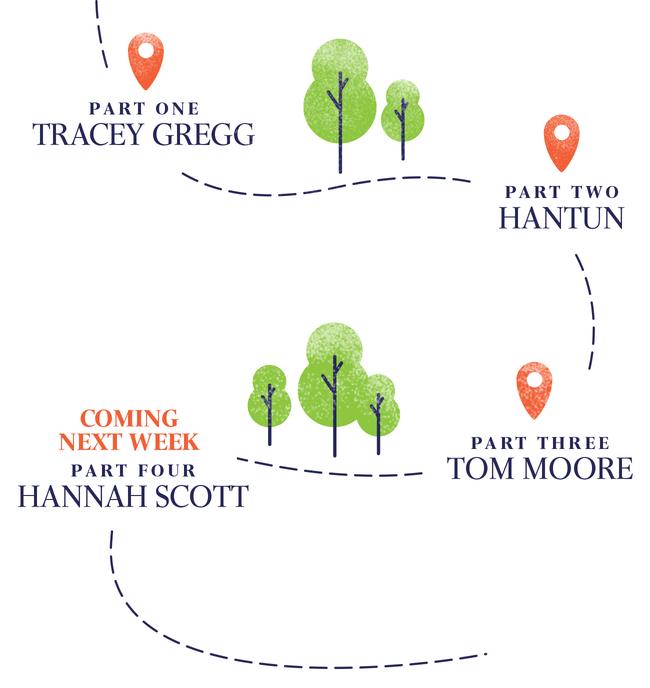

He’s an old soul at just 30, enjoying his second chance at life. In the third part of our six-part series on the residents of Sunny Avenue, we meet Tom Moore.

A portrait of the artist with line trimmer and lawnmower. Squint your eyes and he’s Michelangelo. Tom Moore’s masterpiece is a backyard lawn half the size of a tennis court in the middle of Sunny Avenue and it needs his hose water today the way his girlfriend, Juliet, needs his understanding. A million blades of grass standing to attention like soldiers on parade. No platoon left uninspected. A straight and true lawn edge the width of his thumb between the grass and the concrete pathway skirting the two-level timber house. Green grass and the suburbs. Green like the $100 notes he never finds in his wallet. Green like the cap on Steve Smith’s head over summer. Green like a neighbour’s envy. He likes the lawn to be perfect because he’s a perfectionist like his dad. Lawns like this only come from kneeling. Get your head low to the grass and then cast your sun-damaged eyes along the lay of the land like a golf pro on Augusta. Tom gets his head so close to the lawn he can smell that rich chocolate mud cake soil deep beneath the suburb of Wavell Heights, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia, Earth. That’s the smell of the world turning beneath him. The smell of every elusive answer to every burning question he’s ever asked while hosing the lawn in the cooling Sunny Avenue afternoon with a Corona in his hand and a durry in his lips. Who am I? How did I get here? Why the hell was I put on this spinning rock in the first place? What does someone as beautiful as Juliet even see in a bloke like me? Why did that lady reverse so fast out of the driveway and hit that traffic island signpost that fell straight in front of my moving car?

Squint your eyes and he’s Plato with a garden hose. But then a Sunny Avenue crow calls to a friend and the artist snaps from his dreaming and he realises he’s wasting water in a time of unprecedented drought, which is surely selfish and bordering on un-Australian. But what does that even mean anymore? He’d tell you all about being un-Australian if he knew what it was to be Australian in 2020. Best to focus on being human. Best to focus on being Tom Moore. No easy breeze being Tom Moore. Some days being Tom Moore is a pride-swallowing shit show of strictly rainy days and Mondays. Some days being Tom Moore is a triumph, a 24-hour Everest summit, a raised fist pointed to the sky. Some days it’s just a nice walk across a freshly mowed lawn with no shoes on.

The house belongs to Juliet’s parents, who after 25 years of marriage are going through a divorce that is putting a strain on the physical and mental health of Juliet’s mum. Juliet’s dad moved out and she and Tom moved into the granny flat adjacent to the main house in February last year to care for Juliet’s mum. The divorce makes no sense to Juliet. Her father is a builder. He bought and renovated homes. He flipped homes before flipping homes was a thing. Juliet is 26 years old. She lived in 11 different homes before the age of 10, when the family moved into this house at Sunny Avenue. This house – sweeping decks, cone-roof sunrooms, fairytale balconies – was meant to be the family’s “forever home”. It was the one they worked so hard for. But now Juliet wonders what all that work was for if it was only going to end in the end of her mum and dad’s marriage. Now she’s lost faith in marriage. But she hasn’t lost faith in Tom.

Tom likes it here on Sunny Avenue. He likes the neighbours. He likes the breezes that rise up towards his higher side of the street. He likes the grass. Between subcontractor jobs as a landscape gardener and construction labourer, he does the maintenance around the main house while having occasional long chats with Juliet’s mum about living through life’s rainy days, a topic he feels strangely qualified to comment on, despite his relatively young age of 30. Tom has a couple of favourite sayings and one of them is, “A wise man once said nothing.” When he says that to his friends over beers he’s making a comment on that very human tradition of speaking at length on a topic one knows nothing about. Never in his life has he encountered more experts. Experts driving cabs. Experts on the construction site. Experts at the bar. Every bastard with a phone and a thumb wants him to know their thoughts on politics, climate change, culture, sport and morality. He’s no expert on international politics so he tries not to talk at length about it. He’s no expert on carbon emissions reduction so he tries not to talk at length about it. There are, however, many things he feels qualified to talk at length about. The structural integrity of rock materials beneath mining sites across Australia. Archery. The music of Metallica. Human papillomavirus infection. Clandestine hydroponic marijuana production. And rainy days.

He grew up in Albany Creek, 20 minutes’ drive north of Sunny Avenue, with his mum, Patricia, his dad Russell and his brother, Chris, who is three years younger than him. He has a tree tattooed on his shoulder with branches and leaves holding various symbolic images that represent members of his family. A raven resting on a branch is Chris. Wise and quiet and watchful. A skull resting inside the tree is his father. A serious man, a perfectionist who worked himself to the bone. And there is a rose inside the tree representing his mother. “She makes the chaos pretty,” he says. “Us boys are in the background tearing each other’s heads off and she’s out front making us look all pretty.”

Tom’s father built luxury boats for a living. It’s not always easy being the son of a man who can take several lengths of wood and join them together to form a perfect 70ft yacht and then single-handedly sail that vessel off into the sunset. Growing up, whenever Tom considered a career, every life he saw for himself seemed pedestrian compared to the life his father was living out before his eyes. His earliest boyhood memories involve the sun on his father’s shoulders, fishing from boats anchored off Moreton and Stradbroke Islands. Fish were fat and plentiful then. All he seemed to need to catch a fish back then was a worm and a hook. He visits the same fishing holes today and he has to work twice as hard to catch a fish despite being twice the fisherman he was as a boy. He whispered to the sea the other day. “We’ve really f..ked this place up,” he said. But fishing’s not always about the fish. Fishing’s about standing on the edge of the ocean with the world behind you. Sometimes the world is more beautiful when you have your back turned to it.

When Tom looks back on those years growing up with Chris, wrestling in bedrooms and running across mowed lawns and sharing soft drinks and sucking on ice blocks, he feels ashamed because he’s certain he bullied his brother too often. He was too hard on Chris and he knows the reasons were related to his own insecurities as a boy. People always said Tom was a shy boy but he knew the truth. He was a scared boy. He lived with a chronic anxiety that bled into bouts of depression that were only properly addressed when he saw a therapist at the age of 20. He felt removed from the other kids at school. Detached and different. He excelled in solitary sports. Swimming endless laps on his own in a pool. He won several medals in archery, where he could stand for hours staring at a black, blue, red and yellow target. Draw the arrow. Set. Pull back. Release. Repeat. He remembers being 13 years old and wondering why his classmates at Albany Creek State High School weren’t as interested as he was in where we go when we die, what was beyond the stars up there in the sky, why on Earth he was so sad all the time.

He often apologises to Chris when they’re having beers in the granny flat and Chris says he never has to apologise but Tom insists on it. If he’s had enough Coronas, he stares at his younger brother and he says he was going through some things in his head back then and then he says something awkward like, “I love ya, mate”, and tears form in his eyes but just as those tears are about to run he jumps up from the lounge and fetches two more beers.

Chris is a hard-working carpenter who bought his first home last year. Tom is convinced the secret to his younger brother’s success in life is the fact he’s never been in a serious relationship. He’s never been in love. Tom’s fallen in every kind of love a bloke can fall in. Good love. Lost love. Mad, bad and dangerous-to-know love. He could swear sometimes he set Chris on the right track in life just by his examples of what not to do. He believes Chris took one look at his life and decided to focus on work and staying single. Tom believes untrue love is expensive. Love that is not true must inevitably be a cost to heart and hip pocket. There is no room for near-true with love. Half-true. Close-to-true. It has to be all true and if you don’t have all kinds of true from start to finish then you are all kinds of ruined. Tom can pinpoint the precise moment when his adult life got so complicated. He was fresh out of high school and working as a storeman for Amart Furniture in Lawnton, north of Brisbane. He was earning $700 a week with overtime and carrying mattresses that weighed 50kg. He was healthy. He was happy. “Then I met a girl,” he says.

He believes first love is overrated. First love is a teenager’s malady as ridiculous and conspicuous as a throbbing zit on the tip of a rosy red nose. First love was a fever dream for Tom Moore that he endured for five years before he was woken up by his own severed heart. If there were people warning him about her then he wasn’t hearing. First love is as deaf as a post. If there were signs it was going south then he wasn’t seeing. First love is as blind as a bat. She left him. There was another man and she fell pregnant to him. Then Tom discovered he had contracted the highly contagious sexually transmitted human papillomavirus (HPV). First love stings like a bitch. The virus went away but the heartbreak lingered.

He wanted to sail away after that. He wanted to build himself a 70ft yacht out of yellow cedar and sail it to the edge of the world and if he ran out of world then he could sail off into space. But he couldn’t build boats like his old man so he found himself another vessel to sail away on. “Drugs,” he says. He was working in construction and the drugs in that industry were as easy to obtain as the money to buy them. He came up with the idea to take drugs all by himself. He remembers the notion landing like a lightbulb moment. As bright an idea as someone deciding to paint their porch sunflower yellow. Metallica should write a song about it some time. A thunderous Lars Ulrich drumbeat. Lyrics by long-troubled frontman James Hetfield. An epic metal anthem for the modern Australian construction worker and it goes something like this:

“Everyone’s getting paid so much money and we don’t know what to do with it,” Tom says. “I’m working hard during the day but I’m feeling so shit inside. I’m getting paid $500 a day and I’m thinking, ‘Why are you giving us dumb pricks so much cash? What do you think we’re going to do with this money’? Then everybody goes and buys an $80,000 car because we have all this cash but the car doesn’t make us happy. And then all of a sudden the job site closes down and you realise the builders have been bullshitting to your face about how good things are going and you believed the bullshit while the banks were already ripping them to shreds. And we’re all left wondering how we’re gonna pay off our $80,000 cars. ‘Oooohhh, OK, there goes my credit’. Then people are dropping like flies around you and you feel even more shit inside. Well, here’s an idea. Maybe I should start taking drugs and that would make me feel better? Sure as hell couldn’t feel any worse.”

Party drugs mostly. Methamphetamine and “green”. He had three vices in those days. Drugs, booze and gambling. He says a human can live a functional life with a maximum of three vices. “If you have four, you are done.” He calls it the “dirty world”. It was a place to get lost in. No past and no future in the dirty world. Only today. Then, inevitably, the dirty world got dirtier and people in it started doing harder drugs and people in it started dying. “Then came the epiphany,” Tom says. I’m not dead, he told himself. I’m not in jail. I haven’t hurt anyone but myself so far. “If I stop all this now,” he recalls thinking, “I can get out of here with my life.”

Tom wheels out the garbage bins on bin day. He stands on the kerbside some days and looks left and then right down Sunny Avenue. He sees his neighbours put their bins out and he nods hello to them, politely. Some days he wonders if they would have any clue about the life he’s lived for the past decade. All his stumbles and falls and all his climbing the walls and climbing back up to his feet. There’s a tattoo on his forearm of an Oscar Wilde quote: “Every saint has a past, every sinner has a future”. “It’s about how I lost everything and then how I got it back,” Tom says.

He left that dirty world behind. He landed a good job in a construction materials testing lab in north Brisbane. He helped test the structural integrity of rock content beneath dig sites owned by major mining companies. “Basically testing samples so they could figure out where they could put explosives,” he says. The job took him to Perth to live before the mining boom slowed and he drove back across the country and back into construction work and landscaping.

He feels like he has everything now mostly because he has Juliet and she’s mostly everything. They met in 2017 at a party. Tom remembers the words he said to himself the moment he saw her. “F..k, she’s shitfaced,” he told himself. That was followed by another thought. “F..k, she’s beautiful.”

Juliet has a job as a receptionist in a Brisbane hotel. Tom loves Juliet. He writes songs for her on his guitar. Juliet sees Tom as an onion. He has many layers and he sometimes makes her cry. But he’s much sweeter than an onion. He’s too sweet sometimes. She thinks all the rainy days in his life have caused him to have too much of a soft spot for scumbags who take advantage of him. But he can live with being taken advantage of. He can’t live with letting a friend down.

The other day a friend said something funny to Tom that stayed with him. “I know two crazy people,” the friend said. “And you’re both of them.” That’s a fair enough assessment of how he feels most days. He’s still searching for the right Tom Moore to be. The past decade has been so nuts that he’s hardly had time to settle on one definitive version of himself. Maybe he never will.

Every saint has a past. Every sinner has a future. And in between, Tom says, are all the people randomly reversing out of their driveways into traffic. If there was a moment of clarity in his life, this was it. It happened between the drugs in the dirty world and the job with the testing lab. He was driving along not far from Sunny Avenue and the road was wet. Inside a house a woman was having a heated argument with her partner. She stormed out, rushed to her car and reversed wildly out of her driveway across a traffic lane and smashed straight into a pole on a traffic island. The pole fell onto to the other side of the road, right in front of Tom’s moving car. He survived the crash but totalled his vehicle.

He calls this moment his “factory reset”. That crash so easily could have killed him. He realised in the moments that followed how much his life had become entwined with the lives of a couple of strangers having an argument inside a house on a rainy day. He realised also how easy it is to lose everything and by everything he means not just Juliet but life itself. Before that pole fell he had been so caught up in his past that he hadn’t realised how excited he was by his future. It feels like it’s taken him 30 years to look forward to it. It’s not raining so much anymore in his future. It’s all so sunny now, all so lit up. The bins on Sunny Avenue are black, the skies are blue and the grass grows greener every day.

Next week: Hannah Scott’s story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout