Chris Dawson, Hedley Thomas and the personal secret behind The Teacher’s Pet

Hedley Thomas reveals for the first time the personal family tragedy that drove him to pursue The Teacher’s Pet story harder than anything else in his career. | LISTEN to an exclusive audiobook extract

It is late in the afternoon on the last Friday of October in 2017 and the office of The Australian in Brisbane is quietening down near the end of the week’s news cycle.

I’ve started drafting an email at my computer in the corner, which affords a view across a dozen work desks in a messy office enclosed with glass in the heart of a building I’ve known well, on and off, over the previous three decades.

There’s no natural light in this part of the edifice in Bowen Hills where, as a 21-year-old, I would watch in awe as hot, thundering printing presses churned out the newspaper. As young reporters my friends and I would come here at midnight to grab a newly printed first edition and we’d marvel at how our stories had been used. Now the presses are long gone, replaced by smaller versions far from here printing fewer papers with earlier deadlines. I get up and walk past files of months-old newspapers. Constant chatter from talking heads, reporting and commenting on the day’s news, bears down from TV screens on wall mountings above framed front pages. Some of the Queensland office’s biggest scoops are hung up there. My friend Michael McKenna, a dogged reporter and a much-admired chief of our Queensland bureau, sits fidgeting at his cluttered desk – separated from the rest of us by a door he pulls shut – as I start to explain a story I haven’t picked up for 16 and a half years. A cold case.

The Teacher's Pet

The secret behind the crime story of the decade

Hedley Thomas reveals for the first time the personal family tragedy that drove him to pursue The Teacher’s Pet story harder than anything else in his career. | LISTEN to an exclusive audiobook extract

How Dawson’s legal gambit almost derailed the case

If the former teacher succeeded in his bid, the fallout and potential financial costs would have been disastrous. Lyn’s family would be inconsolable, their last chance dashed.

Inside the making of The Teacher’s Pet

Five months into the investigation, a good friend said I was seriously, unhealthily stressed. Then followed a stroke of luck that changed everything.

Shadow of betrayal clouds a young life

The daughter of convicted killer Chris Dawson recalls the cruelty of her childhood in the memoir, My Mother’s Eyes.

Revealed: All the secrets of The Teacher’s Pet

Hedley Thomas still has the first notebook he ever used to take notes about Chris Dawson. He will tell the whole story in a new book.

Dawson’s daughter wonders if her dad blames her

The eldest daughter of murdered mum Lyn has written her own book and tells The Australian of her complex feelings towards her imprisoned father.

Time to put things right for Dawson’s victim, Minister Car

The woman who survived Chris Dawson deserves our thanks. Not more victim-blaming from the NSW education department.

The final shame of an evil old man

This is it. The final, unsatisfying act in an almost unbelievable drama that opened 43 years ago on the playground of a public high school on Sydney’s sun-kissed northern beaches.

Dawson’s twin ‘had sex with me as a teen’

Paul Dawson is facing serious allegations of having sex with underage girls, after one of his former students claimed he took advantage of her.

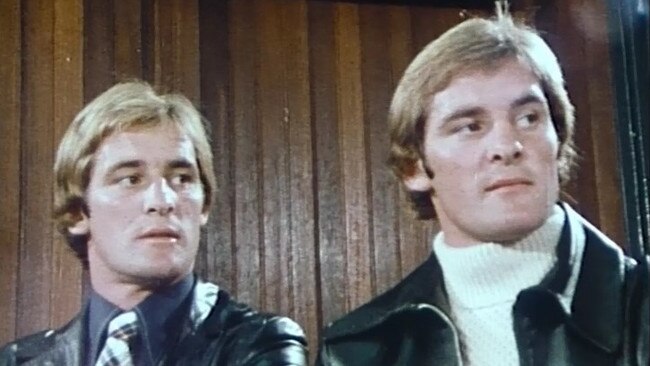

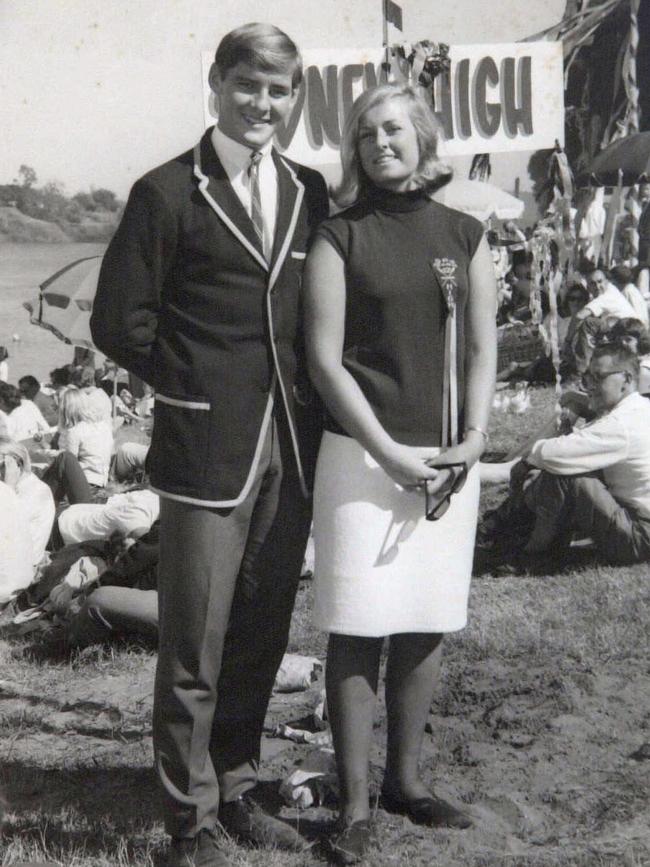

I tell him about a woman in her early thirties, a nurse, named Lynette Joy Dawson. How she lived with her rugby league star husband Chris, a schoolteacher who played for the Newtown Jets in Sydney with his twin brother, Paul.

“Lyn and Chris had two little girls. They lived in a picturesque place called Bayview on Sydney’s Northern Beaches,” I tell Michael. “Dawson is infatuated by a teenager from his school. He gets her into the family home as a babysitter to the two Dawson daughters. Dawson is having sex with the girl there.

“Lyn finds out. It’s an impossible situation.”

Impossible, until the day Lyn suddenly vanishes and Chris Dawson’s problems melt away.

It is as if the universe swallowed the lively, warm and loving woman, serendipitously delivering Dawson uncontested custody of the children, ownership of the marital home and the sexual freedom of a single man.

Lyn vanished on January 9, 1982. Michael and I were then teenagers on school holidays, he in Brisbane and me at Main Beach on the Gold Coast. Michael is a coiled spring of energy and contagious curiosity. I can see he’s intrigued by the story. I go on to tell him that the teenager marries Chris Dawson, who was twice her age when he zeroed in on her in the playground of Cromer High. They have a child in 1985 but within five years they’ll separate, then go through a divorce.

“And nobody hears from Lyn again.”

He’s hooked now.

Michael is a reporting bloodhound. His intuitive news sense – the difference between adequate reporters and great ones – is acute. His commitment to breaking yarns – from political and corruption scandals in Canberra and Brisbane to digging deep into some of Queensland’s most heinous crimes, to shining a light into dark corners of remote Indigenous communities – has inspired all with whom he has worked. On this balmy Friday afternoon, I’m trying to make a sales pitch and get a concrete commitment. I’m telling Michael why it would be a good idea for me to drop other stories I’m working on to concentrate on just one. Lyn’s case.

And not for just a week or a fortnight. At a time in journalism when job-shedding and the farewelling of our friends and colleagues from once-boisterous, busy newsrooms has become depressingly repetitive – an era of digital click-bait, in which the demands of bean counters to squeeze more from less have put heavy burdens on editors and everyone down the chain – I need Michael’s blessing to give me free rein on one story for perhaps six months. “I think it can be solved,” I tell him. “If I do it as a podcast.”

It’s an enormous ask. I’ve never done a podcast before. Audio and narration are a new medium for a reporter who started when the clatter of typewriters filled newsrooms. In the true crime podcast space, I’ve only heard a few: American broadcaster Sarah Koenig’s 2014 podcast Serial about Adnan Syed, a convicted killer who denied slaying his former girlfriend Hae Min Lee in Baltimore in 1999, was the first.

Newspaper journalists are, in the main, soloists who recoil from the long arm of management. We persuade ourselves that we do our best work when left well alone to go away and dig and dig. It presents impossible challenges for editors, who must fill the newspaper every day.

Michael’s unenviable job includes balancing the endless daily needs of the paper with the independent spirit of quixotic journalists spouting grand ideas and big promises with rubbery deadlines. He wants to know about the progress of the other stories I’ve been working on. Nothing has been converted to newsprint yet. The truth is that since my father died earlier in the year, none of the stories I would once have tackled with relish have felt worthy. My father’s strong interest in my reporting – his encouragement and feedback – were powerful motivators. I was named after him, so my byline was also his.

I give Michael a pessimistic update on two of my incomplete investigations, then return to the topic at hand. “Lyn’s story is special. I’ve known this for 16 years,” I tell him. There’s an urgent plea in my pitch. If I can secure Michael’s backing, it will be easier to convince editors in the Sydney head office of the need for a lengthy, costly investigation. And that it needs to be done through this unfamiliar new form of journalistic storytelling: the podcast.

As Michael hears me out, my colleagues Trent Dalton, Sarah Elks and Jamie Walker file their stories for the fast-looming weekend edition. I’m ending another week without a yarn. At times like this it’s hard to shake the uneasy sense that you’re an impostor on the brink of being exposed. No matter how many stories you’ve broken or reported, journalistic insecurities bubble just below the surface. Regular bylines quell the unease, a journalist’s measure of self-worth. Going without for a few days elicits despair and an irrational, gnawing fear that faceless readers and colleagues are noting your absence from the paper. Keeping score.

Nine hundred kilometres away in Sydney, subeditors are deftly removing typos from the reporters’ copy which is arriving on, but mostly after, the tight deadline. Sentences are being snappily rewritten and headlines and photographs placed. If it all works as intended, they’ll draw the reader into the story. Somebody in the business will count the clicks. Keeping score.

“I agree, it sounds remarkable,” Michael tells me. “Do you think you can crack it?”

“Yes, Mickey. Absolutely.” I’m overselling now. I need a green light.

He agrees.

The thrill of an exciting new challenge has given me a happy charge. It must be adrenaline. I’ve now got the most valuable commodity in investigative journalism: time.

I return to my desk to continue drafting the email to Greg Simms, Lyn’s brother, a former police officer with whom I’ve had sporadic email contact since I first looked at Lyn’s case in 2001. I read the email over and over. It’s vital to get the tone right and leave no room for misunderstandings.

Even though there’s never been any trace of a body, I’d long held the view that Chris Dawson had probably got away with Lyn’s murder. I didn’t want to come straight out with this assertion in writing, even though Greg needed no convincing.

I held out to Greg the promise of a breakthrough – we may only hope that it would finally produce a result – and emphasised my keenness to start immediately. I was anxious to build momentum.

I had personal motives, too, but Greg didn’t need to hear about my father, who grew up on Sydney’s Northern Beaches. His mother had disappeared from that place, from her two children, when she was in her thirties, just a little older than Lyn.

Like Lyn, my grandmother was never seen by her children or friends and loved ones again.

Like Lyn, she was ephemeral and shrouded in mystery. We scarcely talked about her when Dad was alive because I knew how much it pained him.

I remember my mother telling my sisters and me when we were small children that Dad would walk around street corners and through shopping centres and other busy public places, scanning the crowd for his mother’s pretty face. He looked for her for many years until he finally accepted he would never see her again.

I knew that Dad always hero-worshipped his father, who had died a year after I was born, but my mother couldn’t stand him. I knew that two of my grandmother’s siblings had died by suicide in the years before Dad’s mother disappeared; that my grandmother probably had depression and my grandfather was not suspected by police of wrongdoing after her disappearance in October 1956.

Mum told me she had heard that searchers found my grandmother’s nightdress on the sand near the waves at Dee Why. It was believed that she had walked into the ocean and kept swimming until she drowned. I had never seen any corroborative documentation. My love for my father was such that I did not want to add to his lifetime of pain by asking about it.

There was much to do on my new project. I felt enormously privileged and excited but also daunted by the assignment into which I’d just manouevered myself. Thousands of pages of inquest transcript evidence, which I hoped to prise from courts and cops, needed to be read and re-read for clues and new angles. Dozens of people mentioned in those pages, in the pages of witness statements or by Lyn’s relatives on the family grapevine would need to be located and persuaded to talk to me.

Neighbours, friends, former footballers and schoolteacher colleagues of Chris Dawson. Reporters who had followed the story in the distant past. Anyone ever quoted in any of the numerous articles about Lyn’s case. Women who went to nursing college with Lyn or worked with her in the hospitals or at a childcare centre on the Northern Beaches. Did any of them have jottings or old cassette tapes from their interviews with police two decades ago? All were on my list for follow-up.

Even some of my own friends and teachers from high school might be relevant. Chris started teaching physical education at my old school in Southport in January 1985, weeks after I had graduated to start work as a 17-year-old copyboy at the Gold Coast Bulletin. The high school connection was another strange coincidence. What were the chances?

As a cadet sports reporter in 1985 and 1986, I enthusiastically reported on schoolboy rugby league contests in which my old school, Keebra Park State High, reigned supreme. I must have met or at least seen Dawson at that time. I was filling the back pages with laudatory pieces about my former school team where he was a prominent teacher and an assistant coach.

I press send at 5.23pm and the email goes to Greg Simms at his home near Newcastle.

It had been almost 36 years since Lyn vanished from the lives of all who knew and loved her, most painfully her two young daughters. Chris Dawson had always strenuously asserted his innocence of any foul play. He had remarried, divorced and married again.

With the sending of that email, the clock was now running down on Dawson’s comfortable life near the beach in Coolum on the Sunshine Coast, about a 90-minute drive from my home in Brookfield, just beyond the suburban sprawl of Brisbane’s leafy western suburbs.

The idea sketched out in a Brisbane newsroom one Friday afternoon would take on a heartbeat of its own as my investigation went on the trail of a schoolteacher who’d got away with murder for nearly four decades.

In 2018, it would grow into the global juggernaut of The Teacher’s Pet podcast. As the 16th and final episode was about to drop in December that year, New South Wales Homicide detectives went to Queensland to arrest Christopher Michael Dawson for Lyn’s murder. This was then followed by three and a half years of tortuous legal proceedings, in which Dawson and his legal team tried everything to show that he was an innocent man. In a bid to permanently halt the planned prosecution, the Dawson camp mapped out a strategy to put me and the podcast on trial. The courtroom battles through 2020, 2021 and 2022, where his legal team waged this fight, were subject to reporting bans at the time; the judges, the lawyers for Dawson and the DPP were concerned that more prejudicial publicity would make it difficult for him to get a fair trial.

The brunette ghost of my grandmother was always there, too, on my mind and in invisible ink on every page of my notes for The Teacher’s Pet. Her ethereal presence nudged me to take bigger risks and fight harder than I had in any other story. I wondered about her when I looked at photographs of my father as a little boy, dressed smartly and holding her hand.

When I wrote to Lyn’s brother Greg Simms on that Friday afternoon in October 2017, none of us comprehended that we had awoken something wild and dangerous, bound up in decades of hurt and mystery. Neither Chris Dawson nor I could have known that only one of us would survive it.

The Teacher’s Pet by Hedley Thomas (Macmillan, $36.99) is out on October 10