How Chris Dawson’s legal gambit almost derailed the case

If the former teacher succeeded in his bid, the fallout and potential financial costs would have been disastrous. Lyn’s family would be inconsolable, their last chance dashed.

In 2020, Christopher Michael Dawson applied to Justice Elizabeth Fullerton to permanently block his prosecution for alleged murder with a determined bid for a “permanent stay”.

The former high school teacher would not go into the witness box to answer questions in his stay application. The accused always enjoys a right to silence. The six subpoenaed witnesses, however, had no choice. We were compelled to give evidence.

The Teacher's Pet

The secret behind the crime story of the decade

Hedley Thomas reveals for the first time the personal family tragedy that drove him to pursue The Teacher’s Pet story harder than anything else in his career. | LISTEN to an exclusive audiobook extract

How Dawson’s legal gambit almost derailed the case

If the former teacher succeeded in his bid, the fallout and potential financial costs would have been disastrous. Lyn’s family would be inconsolable, their last chance dashed.

Inside the making of The Teacher’s Pet

Five months into the investigation, a good friend said I was seriously, unhealthily stressed. Then followed a stroke of luck that changed everything.

Shadow of betrayal clouds a young life

The daughter of convicted killer Chris Dawson recalls the cruelty of her childhood in the memoir, My Mother’s Eyes.

Revealed: All the secrets of The Teacher’s Pet

Hedley Thomas still has the first notebook he ever used to take notes about Chris Dawson. He will tell the whole story in a new book.

Dawson’s daughter wonders if her dad blames her

The eldest daughter of murdered mum Lyn has written her own book and tells The Australian of her complex feelings towards her imprisoned father.

Time to put things right for Dawson’s victim, Minister Car

The woman who survived Chris Dawson deserves our thanks. Not more victim-blaming from the NSW education department.

The final shame of an evil old man

This is it. The final, unsatisfying act in an almost unbelievable drama that opened 43 years ago on the playground of a public high school on Sydney’s sun-kissed northern beaches.

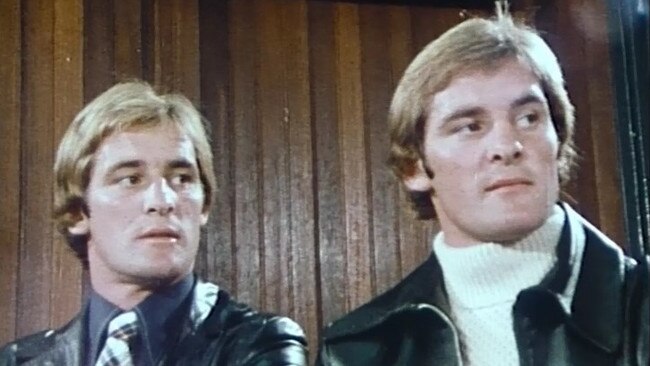

Dawson’s twin ‘had sex with me as a teen’

Paul Dawson is facing serious allegations of having sex with underage girls, after one of his former students claimed he took advantage of her.

While the High Court had made it clear that in an appropriate case pre-trial publicity could result in a permanent stay of a murder trial, “an appropriate case” would very rarely, if ever, exist in practice. The trial courts take all necessary steps to ensure a fair trial, including by questioning potential jurors.

On the other hand, The Teacher’s Pet had been downloaded 50 million times by that stage. It had generated thousands of related stories across the media. None were good for Dawson. I feared that, despite the evidence against him, he might win.

My wife Ruth’s elderly parents, Iain and Mary, who lived with us, were frail and their immune systems were compromised. The Homicide Squad’s Dan Poole, who had been methodically going through my files and following up leads, assured me I should be able to give evidence via a video link in Brisbane to the Supreme Court’s hearing in Sydney.

When Ruth’s father took a serious turn and needed an emergency admission to hospital, it seemed a foregone conclusion that Ruth and I would not be made to travel. We feared Iain was dying and would not get out of hospital. Our family GP, who was gravely worried about his condition, wrote a letter stressing the risks and imploring us to not travel. This was during the height of the pandemic. Going to Sydney could mean returning with the virus.

My barrister retained by The Australian, Dauid Sibtain, set out the medical position in preliminary hearings. My strong preference to testify from Brisbane was firmly rejected. Justice Fullerton required me in her courtroom in Sydney. I opted to drive the 900km with Ruth to lower the risks of contracting Covid-19 on an aircraft or in airports. I used the 11 hours in the car to re-read files and join telephone conferences with the lawyers.

It had been 19 months since the podcast series had ended, with a 16th episode being updated and produced by Slade and me on the day Dawson was arrested for alleged murder. I had spent more time meeting the demands of police, the Office of the DPP, the defence, and The Australian’s lawyers than I had investigating Lyn’s case and writing The Teacher’s Pet.

If Dawson succeeded in his bid for a permanent stay, the fallout for Lyn’s family and friends, journalism, The Australian and me would be disastrous. I had been acknowledged as the reporter who single-mindedly, perhaps obsessively, drove the story. It was cast in a positive light during the series and soon after the arrest. But if the pendulum should go the other way with the termination of a murder prosecution because of the podcast, severe criticism and blame would undoubtedly come our way. My editors and colleagues would be tarred with the same broad brush. The potential financial costs for the newspaper and me could have been calamitous. Lyn’s family would be inconsolable. Their last chance dashed.

In my suitcase, a medication known colloquially as “beta blockers” was at the ready after a recommendation from a friend who swore by them to quell stress and nervousness in unusual situations. A couple of hours from Sydney, in the gloom of a winter’s early evening, Ruth slept soundly in the passenger seat while I drove. My stomach was in knots and my head throbbed.

Tired from driving after little sleep and long days preparing for a courtroom interrogation, I had become irrationally convinced that the malevolence of Chris Dawson could bring down those who posed a serious threat to him.

This despondency was hard to shake. The Australian’s new editor-in-chief Christopher Dore called to wish me well as I drove into the hotel car park. We had been friends for many years. I knew he would back me, double down and run a powerful new campaign if an alleged killer ultimately achieved prosecutorial immunity. But it would still leave an ugly stain on the newspaper and our journalism.