‘Lynette was treated as completely dispensable’

Here is a transcript of Justice Ian Harrison’s sentencing of Chris Dawson.

HIS HONOUR: Christopher Michael Dawson was convicted on 30 August 2022, following a trial before me sitting without a jury, of the murder of his wife Lynette Dawson on or about 8 January 1982. He now stands to be sentenced for that crime. The facts found by me in my verdict judgment (R v Dawson [2022] NSWSC 1311) are relevant to the determination of the sentence I am required to impose. Having found those facts, it is unnecessary to repeat all of them now. However, a summary of those facts for present purposes includes the following matters.

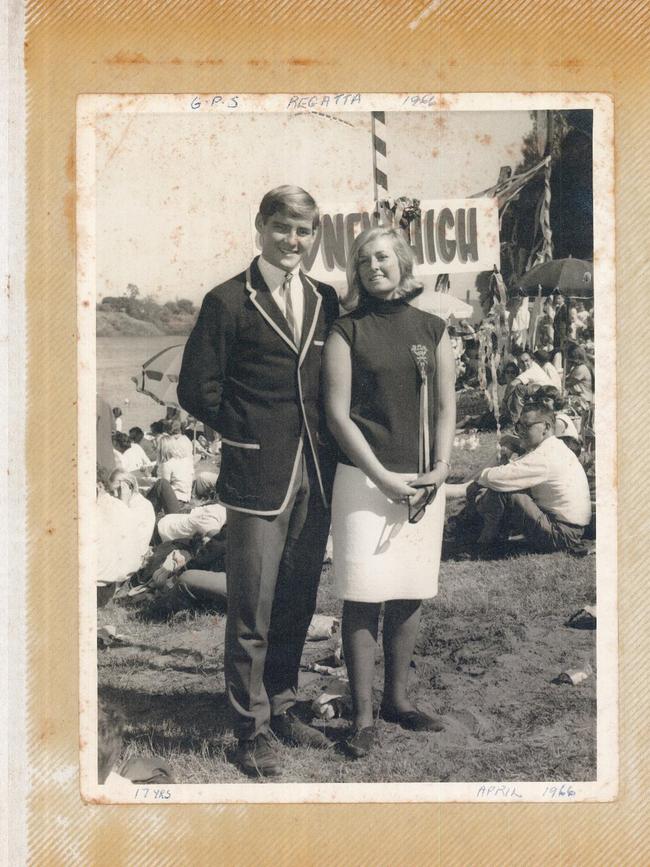

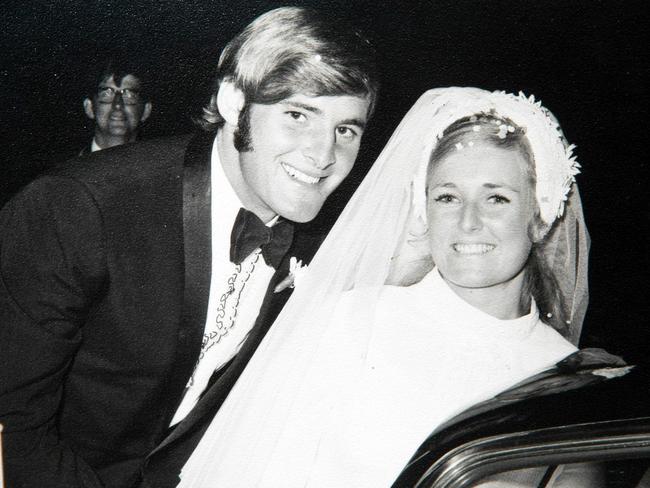

Mr Dawson and Lynette Joy Simms married on 26 March 1970. They were then 21 years old. As at 8 January 1982, they were living at X Gilwinga Drive, Bayview with their two daughters. Lynette Dawson was a trained nurse working at the Warriewood Childcare Centre. Mr Dawson was a teacher at Cromer High School.

JC was a student at Cromer High School from 1976 until she completed her Higher School Certificate in 1981 at the age of 17 years. From time to time during 1980 and 1981, JC worked as a babysitter for the Dawsons’ daughters. At some point during that time, Mr Dawson and JC commenced a sexual relationship. Due to difficulties in her own home, JC moved into the Dawsons’ house for a brief period late in 1981.

In 1980 and 1981, JC was subject to Mr Dawson’s significant influence. However, that dramatically changed after Boxing Day 1981. JC began living with her sister at Neutral Bay on 27 December 1981. Although Mr Dawson spent New Year’s Eve alone with her in 1981, JC travelled to South West Rocks a day or so later. Consequently, and for the first time since their relationship started, JC was not only beyond Mr Dawson’s physical reach and control but also beyond his emotional sway. She was instead in the company of other young women, and significantly young men, of her age, including those who had so plainly and recently concerned Mr Dawson. Mr Dawson was hundreds of kilometres away from her, with no knowledge of what she was doing or with whom, while he remained in Sydney with his wife who he had only days before shown himself to be more than enthusiastic to leave. Mr Dawson had a possessive infatuation with JC that affected him very significantly in the period commencing with JC’s departure for South West Rocks. JC had communicated her desire to end their relationship at around this time and Mr Dawson did not want that to occur.

Mr Dawson’s motive to kill his wife evolved and developed in response to his desire to be exclusively with JC. The prospect of losing her distressed, frustrated and ultimately overwhelmed Mr Dawson to the point that he resolved to kill his wife.

The evidence does not reveal how Mr Dawson killed Lynette Dawson. It does not reveal whether he did so with the assistance of anyone else or by himself. It does not reveal precisely when he did so. The evidence does not reveal where Lynette Dawson’s body is now.

Objective seriousness

Mr Dawson’s state of mind at the time he killed Lynette Dawson is relevant to the assessment of the objective seriousness of the offence. I have found that Mr Dawson killed her by a voluntary act performed by him with the intention of causing her death. An intention to kill is a matter that tends generally to increase the objective seriousness of the offence of murder, in contrast to a death caused by an act committed with an intention merely to inflict grievous bodily harm. Lynette Dawson’s body has never been found so the precise way in which she died is not, and cannot be, known. Accordingly, no valid conclusions can be reached about the nature of the act that caused her death.

Although the precise details of the nature and extent of Mr Dawson’s preparations to murder his wife also cannot be known, I have previously found that Mr Dawson planned to kill Lynette Dawson, having resolved to do so on or soon after 2 January 1982 following the departure of JC from Sydney to spend time with her friends at South West Rocks. Those plans included contriving to have Phillip Day attend the Northbridge Baths on 9 January 1982 so as to facilitate the care of his daughters by others that evening in order that he might dispose of his wife’s body without interruption. That plan was conceived at or about the time of JC’s departure for South West Rocks and so was not a plan that I can be satisfied beyond reasonable doubt was one of long standing.

The fact that Lynette Dawson’s body has never been located or recovered is an aggravating circumstance of the offence of murder. Concealment of the body is not limited in its significance to the absence of remorse: R v Wilkinson (No 5) [2009] NSWSC 432 at [61].

Assessing the objective seriousness of a crime is a synthesis or amalgamation of relevant factors touching and concerning the circumstances of its commission undertaken with the benefit of judicial experience. Reasonable minds may differ as to the conclusion. Murder is uncontroversially a serious crime. In my opinion, the murder of Lynette Dawson is an objectively very serious crime. Despite some evident misunderstanding, it is not necessary in dealing with this issue to state or to describe where on some hypothetical scale of seriousness a particular offence falls. Indeed, references to where, when compared to the oft cited middle of the range of objective seriousness, a particular offence falls are ironically so replete with potentially subjective judicial idiosyncrasies that verbalising the conclusion is usually less helpful than might be hoped. It is the responsibility of a judge passing sentence to indicate clearly his or her view of the objective seriousness of the offence being considered. It is in my view preferable when doing so, and sufficient for me in this case, to say what factors support my conclusion that the murder of Lynette Dawson is an objectively very serious offence.

Mr Dawson planned to kill his wife. Whatever means Mr Dawson employed to kill her, he intended that result. He did so in a domestic context and in her own home. In that last respect, and bearing in mind that I have to be satisfied of factors adverse to Mr Dawson to the criminal standard, and in the absence of direct evidence, I nevertheless find that Lynette Dawson was killed at X Gilwinga Drive, Bayview. I am satisfied to that standard because I consider my conclusion to be the only rational inference that the facts permit me to draw.

Lynette Dawson’s murder was also committed for the selfish and cynical purpose of eliminating the inconvenient obstruction she presented to the creation of the new life with JC that Mr Dawson was unable to resist. Lynette Dawson was faultless and undeserving of her fate. Despite the deteriorating state of her marriage to Mr Dawson, she was undoubtedly also completely unsuspecting. Tragically her death deprived her young daughters of their mother so that a significant part of the harm caused to others, and by inference to the community, as a consequence of her death, is the sad fact that Lynette Dawson was treated by her husband, the father of the very same girls, as completely dispensable.

Victim impact statements

Section 28 of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999, as at the date of Mr Dawson’s arrest on 6 December 2018, was in the following relevant terms:

28 When victim impact statements may be received and considered

(1) If it considers it appropriate to do so, a court may receive and consider a victim impact statement at any time after it convicts, but before it sentences, an offender.

(2) …

(3) If the primary victim has died as a direct result of the offence, a court must receive a victim impact statement given by a family victim and acknowledge its receipt, and may make any comment on it that the court considers appropriate.

(4) A victim impact statement given by a family victim may, on the application of the prosecutor and if the court considers it appropriate to do so, be considered and taken into account by a court in connection with the determination of the punishment for the offence on the basis that the harmful impact of the primary victim’s death on the members of the primary victim’s immediate family is an aspect of harm done to the community.

(4A) …

Statements were read in Court by or on behalf of Lynette Dawson’s daughter Shanelle Dawson, her brother Gregory Simms and her sister Patricia Jenkins. A significant and understandable theme that emerges from these statements is their painful uncertainty over four decades about the fate of their mother or sister, exacerbated now by the latter day clarification of what happened to her and who was responsible for it. I have considered and taken these statements into account to the extent permitted by law. However, I should clearly indicate that I would have arrived at the sentence I intend to impose even without the benefit of the victims’ sentiments expressed in this way.

It can hardly be controversial that in killing his wife, Mr Dawson must be taken to have known and appreciated the injury, emotional harm and loss that his actions were likely to cause to Lynette Dawson’s daughters and her other relatives. The presence or absence of statements from victims of Mr Dawson’s crime does not alter that obvious conclusion, even though in this case those statements eloquently articulate what common experience and understanding of human affairs would otherwise lead one to expect. The significance of a death is not only to be measured by the suffering of those left to endure it.

Subjective circumstances

Mr Dawson was born in 1948 and is currently 74 years of age. He suffers from the physical effects of having participated in contact sport, including professional rugby league, at an elite level in his twenties. Mr Dawson sustained a series of head injuries during this time, including loss of consciousness. More recently, Mr Dawson has sustained injuries in falls also associated with loss of consciousness.

Mr Dawson presently suffers from having sustained a fractured hip, a fractured rib and moderate aortic regurgitation. A brain scan in April 2021 revealed what appears to be microangiopathic vasculopathy.

Mr Dawson was examined a number of times but most recently on 2 November 2022 by Dr Olav Nielssen, a psychiatrist, whose report dated 6 November 2022 was tendered in these proceedings. Dr Nielssen diagnosed Mr Dawson to be suffering from a depressive illness and mild cognitive impairment. He expressed the following opinion:

“The diagnosis of depressive is taken from the symptoms described by Mr Dawson, the observations of Dr Eshuys and Professor Hamilton-Craig and aspects of Mr Dawson’s recent presentation. He described interrupted sleep, feeling anxious and depressed when he woke up, impaired cognitive function, and prominent anxiety, especially when faced with change. He previously reported thoughts of suicide, but not recently. At the time of the recent interview Mr Dawson seemed both anxious, and depressed.

The further diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment is made from his accounts of impaired memory function, Dr Eshuys assessment, supported by the findings of Professor Hamilton-Craig and the MRI scan, and his presentation during the recent interview.

Mr Dawson’s cognitive function looked to have declined since the last assessment, possibly due to the effect of his depressive illness and the lack of external stimuli in an institutional setting with long periods locked in his cell. However, based on the results of serial assessments and the findings of the MRI scan, it seems likely that Mr Dawson’s cognitive difficulties are the early phase of what will eventually be dementia.

With regards further care, Mr Dawson looked to require treatment for depression with supportive counselling by a mental health professional, or with antidepressant medication. He is also likely to require ongoing assessment of cognitive function, and the transfer to higher dependency care if his cognitive decline is found to be progressive.”

Mr Dawson maintains his innocence and consistently with that position has expressed no remorse for his crime. He has no record of any previous convictions, is a person of prior good character and for associated reasons is highly unlikely ever to re-offend. Those matters are also informed by Mr Dawson’s age and the fact that he will be much older by the time he becomes eligible for release on parole. I consider that Mr Dawson has good prospects of rehabilitation although for obvious reasons the significance of that conclusion in this case is necessarily reduced.

I have also taken account of the several testimonials that speak to Mr Dawson’s characteristics as a loving father, a doting grandfather and a loving and loyal husband. These include references from Lynette Dawson’s younger daughter ... dated 31 October 2022, JC’s only daughter KB dated 2 November 2022 and Mr Dawson’s wife Susan Dawson dated 7 November 2022. I note, without criticism, that other testimonials tendered on Mr Dawson’s behalf all pre-date his conviction and would appear to have been prepared for a different purpose. Be that as it may, the fact that they speak favourably of Mr Dawson without an appreciation that he has now been convicted of the murder of his wife necessarily lessens their force to some degree.

Punishment, retribution and deterrence

Although it is well-known, and it is for that reason strictly unnecessary to do so, I consider that the terms of s 3A of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 can usefully be included in these reasons:

3A Purposes of sentencing

The purposes for which a court may impose a sentence on an offender are as follows--

(a) to ensure that the offender is adequately punished for the offence,

(b) to prevent crime by deterring the offender and other persons from committing similar offences,

(c) to protect the community from the offender,

(d) to promote the rehabilitation of the offender,

(e) to make the offender accountable for his or her actions,

(f) to denounce the conduct of the offender,

(g) to recognise the harm done to the victim of the crime and the community.

I have found that Mr Dawson’s crime was inspired by an uncontrollable desire to be with JC. It was neither spontaneous nor unavoidable. It is a crime that should never be permitted to offer the slightest encouragement to any person similarly placed or similarly minded. Mr Dawson’s sentence should reflect the disapprobation with which his self-indulgent brutality must be viewed by Australian society. In plain terms, it is not acceptable to take someone’s life merely because they represent an inconvenient impediment to a particular result. I understand the argument that so-called crimes of passion spontaneously committed are not always a sound vehicle for general deterrence. As will be apparent, I do not consider that the murder of Lynette Dawson fits that description.

In contrast, there is no need to sentence Mr Dawson in a way that specifically deters him from similar reoffending. There is no reasonably foreseeable prospect that he will ever reoffend. He will pose no threat or danger to society upon his release from gaol.

Extra curial punishment

Mr Dawson contends that the publicity that has attended his arrest and conviction has been so persistent and so unremitting that he has been unfairly subjected to punishment extending beyond that to which he might ordinarily have been expected to endure. A report dated 5 August 2021 prepared by Dr Donna Eshuys, a clinical psychologist, explains Mr Dawsons’s position in that respect:

“18. Mr Dawson described being increasingly anxious since publicity around his missing wife escalated with the podcast production by Hedley Thomas. He is often hypervigilant and for many years describes being surprised unexpectedly by journalists who he describes ‘jumping out from behind a tree’, ‘jumping the fence’ or, as occurred on one occasion, a reporter wedging open the garage door as Mr Dawson was trying to close it. This man was disturbed that the media tried to shame him about his close relationship with his twin brother announcing to the world that the twins were ‘weird’. He laments that he and his brother are not invited to their football team reunions and have been effectively ostracised. He was also distraught that the media described him as ‘despicable’ and ‘a narcissist’. Mr Dawson soon began feeling uncomfortable around people and began isolating.

19. He reports his depressed mood has been present for many years, intermittently since his first wife’s disappearance. More recently Mr Dawson describes being overwhelmed, unable to sleep, not wanting to rise from bed, and ruminating constantly about his situation. He repeated his story often and ruminated about the public ‘not being told the truth’, being misled by media and deserving to know truth. He misses his eldest daughter, who no longer speaks to him following the media fiasco. Mr Dawson reported having a recent ‘meltdown’ the week after his solicitor sent him an email regarding the case and, when he perused the documents, ‘everything’, he had been attempting to ‘push’ out of his head, returned with a vengeance. ‘It’s sickening when I’ve always been anti-predators’. As a consequence, Mr Dawson said he went to bed, dry retched and was overcome with tremors.

20. He says he is embarrassed by his decision to betray his wife by starting an affair with [JC]. He feels ashamed for having put his family through all the media persecution. Mr Dawson reports being increasingly frustrated with his cognitive inability and suggests he is not thinking very clearly since his two falls earlier this year. He has suicidal thoughts, some plans but no active intent.”

Mr Dawson submitted that the adverse publicity to which he has been subjected has disproportionately carried over into his current custodial circumstances and that, by inference, it is likely to continue. He is regularly subjected to vilification by other inmates. He is somewhat oddly referred to as “the teacher’s pet”. He is the subject of constant threats of violence, although he concedes that is not an uncommon function of prison life.

It was submitted on his behalf that in the course of this particular matter and over some considerable time, Mr Dawson has been exposed to what was described as “probably the most egregious publicity that one could consider in a context of the criminal law”. I was referred in this respect to the findings of Fullerton J in R v Dawson [2020] NSWSC 1221 and the observations of Bathurst CJ in Dawson v R [2021] NSWCCA 117. Their respective conclusions were to the effect that the publicity generated by the Teacher’s Pet podcast was the worst example of prejudicial publicity that they had experienced. The representations made by the authors of the podcast were said to have portrayed Mr Dawson as an evil, manipulative man, guilty of the crime of murder and otherwise as greedy and narcissistic. The publications involved literally millions of downloads not only throughout NSW but Australia and the world. Mr Dawson and his family have been followed and subjected to unwanted scrutiny.

The publicity affected Mr Dawson both physically and psychologically. It was submitted on Mr Dawson’s behalf that the generated publicity was not a reasonable reaction to the commission of the offence.

The publicity that has attended this crime has undoubtedly been intense. That is to some extent a function of the several decades over and during which speculation about Lynette Dawson’s fate has managed to foment. I would be sympathetic to Mr Dawson’s concern that the media attention will continue to have an adverse impact upon him if it were not for the fact that I am unable to agree that, whatever may have been the position before his trial, it will continue to be unfair following his conviction. Simply put, Mr Dawson’s crime is a matter of intense public interest and the attention he has received is directly referable to that interest. It would be otherwise if media reports had significantly misrepresented his crime in a way that created a false perception of what he had done. His major complaint, when properly understood, is that the publicity improperly made assumptions about his guilt at a time when he was entitled to the presumption of innocence. Mr Dawson has now been convicted of the crime which attracted the publicity in question. In those circumstances, as harsh as it may sound to say so, Mr Dawson is now the author of his own misfortune. Moreover, the critical references by Fullerton J and the former Chief Justice arose in the context of Mr Dawson’s application to stay the criminal proceedings upon the basis that he could not receive a fair trial. His complaints were pertinent in that setting. However, acceding to the proposition that Mr Dawson should now be granted some concession on sentence for the avalanche of publicity that he has received, and will likely continue to receive, would not in my view be consistent with the later intervention of his conviction.

Delay

Lynette Dawson was murdered in January 1982. Mr Dawson was arrested in December 2018. He was convicted in August 2022.

Delay in his prosecution means that Mr Dawson is to be sentenced according to the prevailing sentencing practices at the time the offence was committed, insofar as those practices can be ascertained: Katsis v R [2018] NSWCCA 9 at [38], [74]-[85] and [91]. In this respect I observe that sentences for murder have increased considerably in the years since 1982: R v Hickson (No 4) [2020] NSWSC 340 at [71]-[72]; R v Smith (No 4) [2011] NSWSC 1082 at [23]-[24]; R v Bunce [2007] NSWSC 469 at [93]. The introduction of standard non-parole periods for offences committed after 1 February 2003 has contributed to that increase.

In R v Blanco (1999) 106 A Crim R 303; [1999] NSWCCA 121, Wood CJ at CL said this at [16]:

“The reason why delay is to be taken into account when sentencing an offender relates first to the fact of the uncertain suspense in which a person may be left; secondly to any demonstrated progress of the offender towards rehabilitation during the intervening period; and thirdly, to the fact that a sentence for a stale crime does call for a measure of understanding and flexibility of approach.”

In the present case, the delay between the commission of the offence and Mr Dawson’s arrest and trial are not attributable to the operation of the criminal justice system in the relevant sense. It would be otherwise if Mr Dawson’s trial had been delayed because of a failure by the prosecuting authorities following his arrest to bring him to trial in a timely way. In this respect there are two periods that require consideration.

The first is the period leading up to Mr Dawson’s arrest. Mr Dawson has for 36 years been at large in the community and living what may be regarded as a normal life. He was interviewed by the police in 1991 and apparently discharged himself in such a way that any suspicions about his involvement in the death of his wife were not enthusiastically pursued until many years later. Any state of uncertain suspense under which Mr Dawson may have laboured during that period was a function of the fact that he murdered his wife and might possibly be apprehended, not because he was left wondering what the police or the Director of Public Prosecutions might do thereafter. It could not be said that during that period Mr Dawson was left confused or uncertain as the result of anything said or done by others about what might happen next or when that might be.

The second period follows Mr Dawson’s arrest. I can detect no delay, properly understood, during that period that is or was anything out of the ordinary. Indeed, during that period, Mr Dawson actively agitated for the permanent stay of the criminal proceedings against him. He was entitled to do so but the legal processes inevitably delayed his trial. Any state of uncertain suspense to which Mr Dawson may have been exposed in those circumstances related principally, if not completely, to the unpredictable outcome of his stay application and not to the question of whether the Director prevaricated about whether he intended to maintain the prosecution.

In any event, as the history of this case makes plain, Mr Dawson has enjoyed 36 years in the community unimpeded by the taint of a conviction for killing his wife or by any punishment for doing so. In a practical sense, his denial of responsibility for that crime has benefited him in obvious ways. He married JC and they had a child. Not long after their divorce he remarried and remains so, even though that relationship has suffered in the events that have occurred. It follows that I am unable to accept that Mr Dawson can legitimately embrace the alleged burdens of any delay without simultaneously being required to accept the benefits.

Special circumstances

Section 44(2) of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act provides that the balance of the term of a sentence must not exceed one-third of the non-parole period for the sentence, unless the court decides that there are special circumstances for it being more. In this case, Mr Dawson refers to the following matters in support of a submission that I should vary the ratio between the parole and non-parole periods of the sentence I intend to impose:

• Mr Dawson has never previously been in custody.

• He is a person of prior good character.

• He has good prospects of rehabilitation.

• He will or may require an extended period of release on parole to facilitate his reintegration into society.

• He is 74 years of age and in poor or deteriorating physical and mental health.

• By reason of these matters, as well as the notoriety his crime has attracted, he will find the conditions of incarceration more onerous than most inmates.

In considering this submission, I have taken these matters into account. It is sufficient for present purposes that I indicate that I do not consider that the circumstances warrant any modification of the statutory ratio. Mr Dawson should serve at least the whole of the non-parole period of the sentence I intend to impose. Anything less would not in my view accord with a proper application of the sentencing principles for which s 3A of the Act provides.

Disposition

Mr Dawson is not old by contemporary standards but the reality is that he will not live to reach the end of his non-parole period or will alternatively, by reason of his deteriorating cognitive condition and physical capacity, become seriously disabled well before then even if he does. I am nevertheless required to impose a sentence that satisfies the community’s expectations of punishment, retribution and denunciation. A just and appropriate sentence must accord due recognition to the human dignity of the victim of domestic violence and the legitimate interest of the general community in the denunciation and punishment of someone who kills his spouse: Quinn v R [2018] NSWCCA 297 at [243]. Even though such expectations must be tempered by the need to extend mercy where appropriate, I recognise that the unavoidable prospect is that Mr Dawson will probably die in gaol.

Christopher Michael Dawson, for the murder of Lynette Dawson on or about 8 January 1982, I sentence you to imprisonment for 24 years commencing on 30 August 2022 and expiring on 29 August 2046 with a non-parole period of 18 years expiring on 29 August 2040. The first day upon which you will become eligible for parole is therefore 30 August 2040.

Finally, in compliance with s 25C of the Crimes (High Risk Offenders) Act 2006, I note that the provisions of that Act have potential application to you. Mr Walsh may be expected to provide you with further information about that.

The full judgment as read in court and written by Justice Ian Harrison.