View from The Lodge: former prime ministers John Howard, Julia Gillard and Paul Keating on leadership

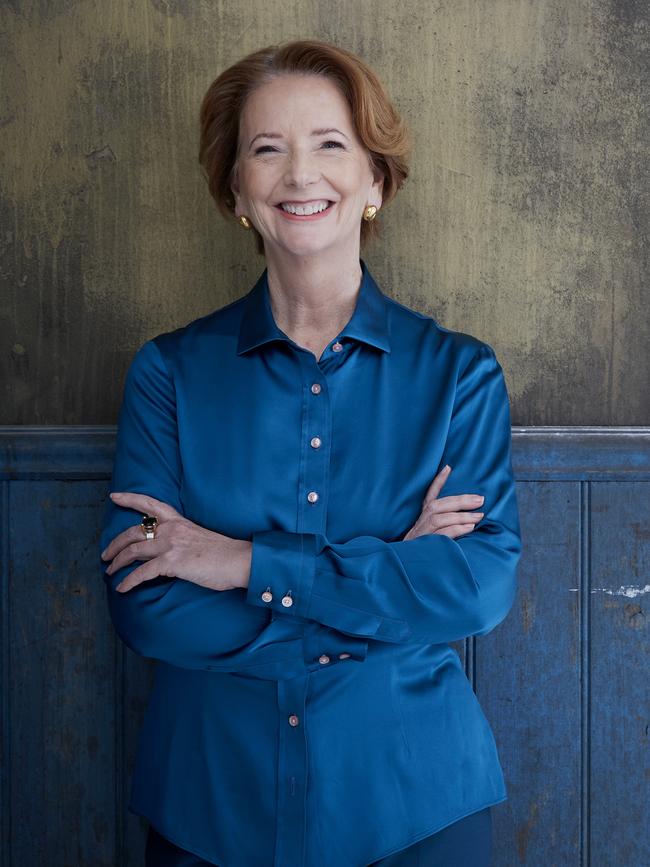

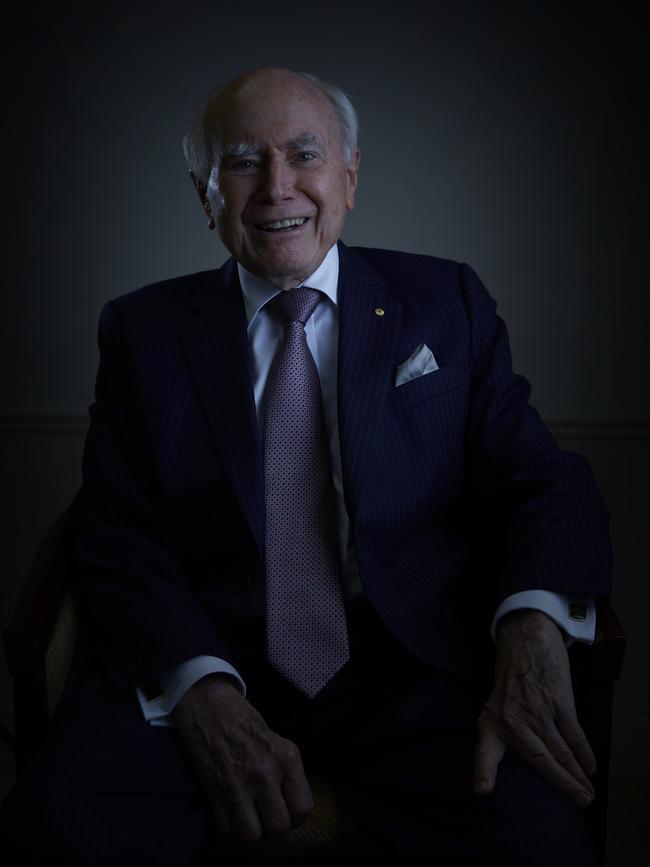

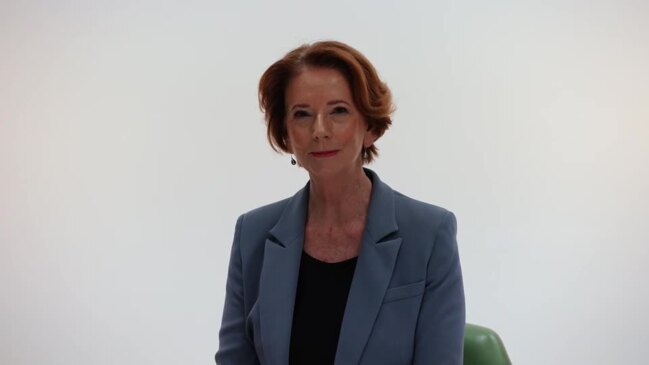

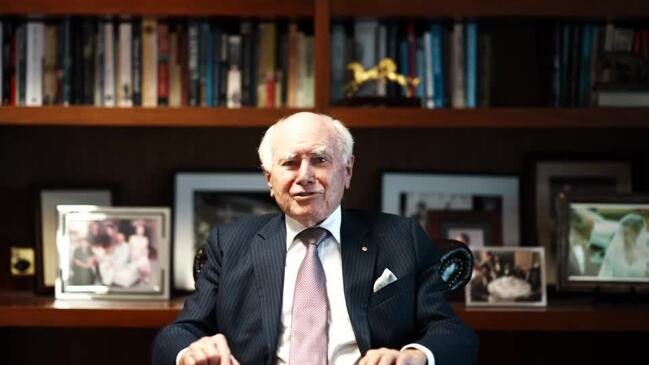

In a series of exclusive interviews with three living prime ministers, John Howard, Julia Gillard and Paul Keating discuss influence and their legacies.

The story of Australia over the past 60 years cannot be told without reference to the influence that prime ministers have had on the nation’s economic development, social and environmental changes, and international outlook and standing. They have led during war and peace, represented us abroad, and sought to unify the country in moments of triumph and tragedy.

There have been 16 prime ministers since the first edition of The Australian was published in July 1964. They came from different states and different parties, with their own unique personalities and pathways to the top job, as well as singular styles and distinctive approaches. But they all had one thing in common: they sought to alter Australia’s trajectory.

Of those, only six prime ministers have had a significant and enduring impact over six decades: two from the Liberal Party and four from the Labor Party: Robert Menzies (1939-41; 1949-66), Gough Whitlam (1972-75), Bob Hawke (1983-91), Paul Keating (1991-96), John Howard (1996-2007) and Julia Gillard (2010-13).

In a series of exclusive interviews with the three living prime ministers named in The Australian’s People of Influence List – Mr Keating, Mr Howard and Ms Gillard – each spoke about their approach to political leadership, how they managed the prime ministership and their respective legacies.

For Mr Keating – who as treasurer opened the economy to the world and energised competitiveness and productivity, and as prime minister sought a new engagement with Asia and established the APEC leaders’ meeting, set up compulsory superannuation, delivered native title and promoted reconciliation, and championed a republic – leadership is visualising a better future and willing it into being.

“Leadership, if it is to amount for anything, devolves to imagination and courage,” Mr Keating, 80, told The Australian. “In public policy and leadership, there is a permanent case for audacity – a permanent case.

“What I always sought to do was to have a Himalayan view of the world. I was glad I was not pushed into the corral of a profession or shunted into a university. I wanted the Himalayan view so I could work out where the pathways were and a mind which was not cluttered – not cluttered by conventions, not cluttered by rules. Without the Himalayan view, you’re only pretending.”

Leadership for Mr Howard – who secured national gun laws, introduced the GST, delivered 10 budget surpluses and paid down government debt, promoted freer trade, reformed welfare and education, and secured the integrity of Australia’s borders – is about understanding the general disposition of the Australian people and with that in mind crafting your policies to ensure they will be supported.

“To try and understand, as best you can, the mood and temper of the people you lead and knowing that, then finding the best way of giving expression to the policy objectives you want,” Mr Howard, 84, said of the task of leadership. “You can’t just do what you think people would like you to do. Equally, you can’t force feed people with a policy diet that they don’t want. You’ve got to try and blend the two.

“You have also got to get the big things right. Anybody who becomes a leader of a political party or prime minister, leader of a company or a general in the army, and says, ‘I’m never going to make a mistake’ – he is doomed to be a disaster. I frequently quote the example of (Winston) Churchill, my all-time political hero. He made some terrible mistakes but he got the big things right.”

Significant reforms

For Ms Gillard – the trailblazing first female prime minister who delivered significant reforms to school and university education, introduced the NDIS and the NBN, initiated the landmark royal commission into child abuse in institutions, and achieved global fame with her “misogyny speech” which has become an emblem of female empowerment – leadership is ultimately about vision and delivery.

“It is about having the vision backed by analytical ability and the capacity to get things done,” Ms Gillard, 62, said of her approach to national public leadership. “When people look at political leaders, they see different amounts of those attributes in different leaders.

“But unless you’ve got all three happening at once, you won’t get big reforms that actually land and start making a difference in people’s lives. And I always wanted to try and get that combination lined up right. Sometimes I achieved it and sometimes I did not.”

Some prime ministers, once reaching the summit of their ambition, use the office to lead the country in a new direction. Others baulk at the opportunity, become imprisoned by the office and shrink in the job. Some offer daring and exciting leadership while others find public support for stability and certainty.

The big picture

The six prime ministers named as the most influential each had a gift for leadership, sometimes having to drag their party and colleagues with them or persisting in the face of public opposition.

They needed intellect, stamina, administrative skills, interpersonal abilities, broad empathy and to be able to persuade in order to leave their imprint on the nation.

Mr Keating argues prime ministers need the Himalayan view and also “a schematic” that outlines where they want to take the nation, why, and how to get there. This is, he says, as important as any skill for effective leadership.

“Without that program, that schematic, then what you are is you’re busy, but you’re not really doing anything,” he says.

“This is one of the great traps of public life. One of the hardest things in life is to sit and ask yourself questions. What does this really mean? What am I really doing? What do I really stand for? Not simply to say, ‘Oh, I had a crowded day, I had 11 appointments and therefore, I’m OK.’ Well, you’re not OK.

“The big picture is really everything. It’s the tabula rasa and you want that, you don’t want the humps and the hollows. You don’t want to start off in life going through humps and hollows of beliefs and conventions. You want the tabula rasa, you want the clear view, and only when the clearer view is there do you see the big picture.”

Communication is key

For Mr Howard, a prime minister must be able to efficiently handle paperwork, communicate effectively, manage people in your party and cabinet, and have the energy to work long hours and under pressure.

“Part of the job is not only to deal in depth with big issues but also to keep the desk clean,” he explained.

“Unless you can process the routine stuff, they become urgent. And that was obviously the difficulty that (Kevin) Rudd found. One of the skills that being a solicitor teaches you, as distinct from a barrister, is handling paper in an orderly and expeditious fashion.”

The former Liberal prime minister, the second longest serving overall, emphasised being able to articulate your ideas in the parliament and to voters. He thought Whitlam was the best parliamentarian during his time in politics. “You should not be in politics if you cannot argue a case,” Mr Howard said. “It amazes me what poor communicators many senior politicians are.”

Ms Gillard preferred it when people she worked with or met were “upfront” and she steered conversations “towards the frank side rather than the more respectful side” to get things done. She explained this was part of the Australian culture. There was also a critical need to manage the physical and psychological impacts of the burden of national leadership.

“Fortitude is a word that’s always at the forefront of your mind – the pace of it in every sense, the physical toll it takes, the psychological toll it takes,” Ms Gillard explained. “It is relentless and you need fortitude in the face of that.

“The ability to decompress and refresh quickly is, I guess, a mirror to fortitude.

“To be able to do that quickly is a great attribute for the job – to sleep well, to get those tiny little pockets of time with friends, family, maybe with a good book, but something that takes you just to a different realm for a while so you can feel yourself re-energising, decompressing and then coming back to it.”

Mr Keating is the only prime minister of the three interviewed who rejected an Order of Australia, arguing the reward for public life is public progress. But he does want recognition for the nation-changing reforms of his government and those of Hawke’s in which he served as treasurer.

“I gave the country an entirely new economy, a new economic model, a new economic engine,” he said.

“And that engine did not falter in 30 years – a record not matched by any other country.

“I completely altered the Labor Party’s protectionist instincts in internationalising the economy. I broke up the party’s propensity for economic envy by facilitating greater economic wealth for everyone – with a turbocharged, growth-focused economy. Real wages just on doubled – the poorest to the wealthiest were shifted up. I also gave the country a new foreign policy – one built exclusively around the centrality of our residence in the Asia Pacific – a new basis of co-operation with Indonesia, engagement with East Asia and engagement with China.”

‘Lacking boldness’

Asked if Australia has the leadership it needs today, on either side, Mr Keating said the country lacked creativity and boldness.

“Because of the major changes of the 1980s in Bob Hawke’s and my government, people think, ‘Oh, this is what you get.’ The answer is: this is not what you get and the chances are you will never get it again. Why? Because the imagination and the guts are not there in the system.”

An important lesson to be learned over the past 60 years is how to achieve lasting reform, Mr Howard argued.

“People will embrace big change if the change is in the interests of the country and the burdens are fairly shared,” he said. “Now, I think what happened with the GST was that for a long time Australians had accepted our tax system needed reform, but they were worried that it was unfair.”

Recalling his negotiations in the Senate on the final taxation reform package, Mr Howard added: “I think we were able to persuade people that we tried very hard to look after anybody who might be adversely affected. And that finally got it grudgingly over the line, but only grudgingly.”

The hardest decision a prime minister makes, Ms Gillard and Mr Howard agreed, is to deploy or maintain a deployment of troops abroad. Mr Howard said his hardest decision was sending troops to Iraq. Ms Gillard noted she attended many funerals for those who had served in Afghanistan.

Out of the wilderness

The Australian’s People of Influence List also details the legacies of Hawke, Whitlam and Menzies. Hawke is Labor’s most successful prime minister and the longest-serving, who reformed the Australian economy with the float of the dollar, deregulating banking and slashing tariffs, establishing an Accord with unions to keep a lid on inflation, introducing Medicare, better targeting welfare payments, doubling high school completion rates, and leading international campaigns to end South African apartheid and save Antarctica from mining.

Whitlam led Labor out of the political wilderness after two decades, and implemented far-reaching economic and social reforms, and reoriented Australia’s foreign policy.

His legacy is felt everywhere, from universal healthcare to needs-based school funding, no-fault divorce and lowering the voting age to 18, diplomatic recognition of China, slashing tariffs, establishing a new honours system and national anthem, and sewering the suburbs.

Menzies, prime minister when The Australian was first published, presided over the great post-war economic boom with rising living standards and an expanding home-owning middle class.

He cemented the US alliance and signed a commerce agreement with Japan. Canberra was developed as the national capital and school and university funding was significantly increased. He is the only prime minister to retire at the time of their choosing.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout