‘I’m not saying I was perfect’: new biography reveals Bob Hawke’s final interview and private archive

Bob Hawke personified the very best and worst in Australians. He was a deeply flawed person, and his behaviour would not be tolerated today.

In February 2019, Bob Hawke sat on the balcony of his sprawling multi-level home overlooking a gleaming Sydney Harbour. The summer sun streaked across his wrinkled face and the blustery wind ruffled his silvery-grey hair. His slim body, tanned and creased, folded compactly into a white plastic outdoor chair. He was slumped and leaning forward, and hardly moved, as if his ageing joints and muscles were fixed. He was not able to get entirely comfortable and the cushion behind his back had to be adjusted several times. But he flashed a smile, cocked an eyebrow and extended his hand in greeting as I sat down to interview him. He smoked a cigar until it extinguished; the stub remained clasped between his fingers. He drained a strawberry milkshake. Hawke loved being outside, soaking up rays like a lizard on a rock. In his final days, it was where he wanted to be. This was to be Hawke’s last interview. He knew the end was near.

The image of Hawke in these final days is lodged in my memory. He was tired and a little irritable. He had lived a long life: he was less than a year shy of his 90th birthday. He was fading. It was deeply affecting to see Hawke ready, even eager, to let go. This son of the manse did not know what afterlife there might be. He had long been agnostic, but never an atheist. He had thought about death, and was coming to terms with it. When I asked how he was feeling, his reply was blunt. “To be quite honest, mate, I’d be quite happy not to wake up tomorrow morning,” he said. Three months later, Hawke was dead.

It soon became clear this interview was different. Although brief in his responses, Hawke was more reflective than usual. He had been thinking about his life. He was concise but thoughtful when recalling his student days, his time in the union movement and his prime ministership. When asked about his parents, Clem and Ellie, or his wives, Hazel and Blanche, or his children, he got emotional. His eyes moistened when he talked about Paul Keating.

Hawke had spoken about how deeply he loved Hazel. He regretted not being a better father to Susan, Stephen and Rosslyn. Or a better husband. He thought he was a better grandfather. He acknowledged his adultery and the impact of the “demon drink” on their marriage. He did not drink alcohol during his prime ministership, but he did not relinquish his insatiable appetite for sex with women he was not married to.

BRAMSTON ON HAWKE

In this last interview, Hawke described his relationship with Hazel as “the most important in my life at that time”. When clarification was sought, he became a little tetchy and made it clear he was indeed talking about Hazel. He had always loved her, even if he had not been faithful. He also loved Blanche. He said she was “the best thing that happened to me”. But he was not faithful to Blanche either. Her care for him in these later years, as he was slipping away, had deepened their love for one another. Hawke had spent a lifetime trying to convince people that he was a simple, “dinky-di” Australian, but in truth he was complex. Most people are. He did not see any difficulty loving both Hazel and Blanche. They were the two great love stories of his life.

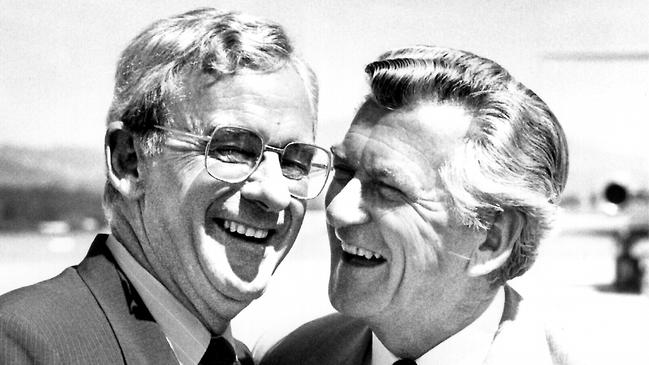

In recent years, Hawke had repaired any lingering rift with Keating. The mending of this relationship had been a work in progress for a decade; it was not a near-death reconciliation. They were Australia’s greatest political duo. They were rivals, and sometimes felt contempt for each other, but there was also a warmth between them. Hawke’s eyes widened and he smiled when he told me how happy he was that he had seen Keating recently. “We had a marvellous time,” Hawke said. “We did a lot of great things together.” He had earlier told me: “Affection is not an inappropriate word, now, for our relationship.”

As he neared the end, Hawke was not interested in pushing a legacy or dwelling on regrets. “I think I handled the prime ministership very well,” he judged. “I’m not saying I was perfect – there were some things perhaps I could have handled better – but overall there is nothing I would change.”

This final interview was an opportunity to ask any remaining questions that might help illuminate the life of one of the most remarkable and consequential Australians. Hawke had given me access to his personal papers, which included diaries and family letters from the 1950s and 1960s, his father’s unpublished memoir, school and university papers, and many notes, briefing papers and letters from his time at the ACTU. An array of archival material from Hawke’s prime ministerial years plus newly discovered documents from the US and UK were also accessed for the first time. Many others were also generous in opening their personal archives.

Bill Hayden allowed me to access the letters he sent to, and received from, Buckingham Palace as governor-general. Hayden’s personal files included two letters exchanged with Hawke about the Labor leadership in 1983. These letters between the vanquished Hayden and the victor Hawke have not been revealed before. They were an essential part of the transfer of power within the Labor Party.

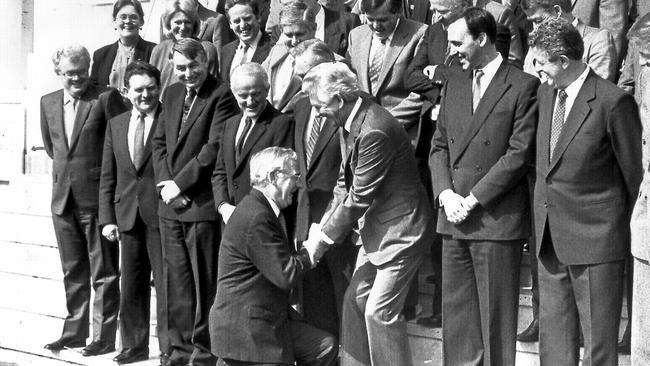

In the summer of 1983, Bob Hawke’s destiny edged one step closer to fulfilment. On the 12th floor of the Commonwealth Government Centre in Brisbane, a deal was made with Bill Hayden to surrender the leadership of the Australian Labor Party. It was done in Hayden’s office, with Lionel Bowen, John Button and Don Grimes also party to the agreement. Hayden, who had reluctantly decided to resign, wanted to clarify and confirm the details of the transition, and seal it in writing. These twin documents were the foundation stone for the Hawke Labor government.

The negotiations took place during a morning tea break at a shadow cabinet meeting while their colleagues waited for them to return. It was February 3, 1983. The meeting in Hayden’s office began just after 10.40am (Brisbane time). About half an hour later, as they were discussing the terms of the leadership transition, there was a knock at the door. “Malcolm Fraser has gone out to see the Governor-General,” a staff member said. Hawke, Bowen, Button and Grimes laughed. Hayden was speechless. On this day of double drama, there would be a new Labor leader and the announcement of an early election to be held on March 5. It was time to finalise the leadership agreement.

When the five men returned to the shadow cabinet meeting, their eyes were red and moist, and they were exhausted. Their colleagues were informed of the leadership change, which would be formalised at a caucus meeting within days. Tears had been shed during this morning of tragedy and excitement. It had been a gut-wrenching decision for Hayden. It was a moment of triumph for Hawke that was tinged with sadness but no regrets.

Hayden, with his heart in his throat, had sought to extract several guarantees from Hawke regarding the futures of his staff, his colleagues and himself. The letters would be Hayden’s insurance. They bound Hawke to a written contract that would last for years. “In standing down as Leader I will be making a number of sacrifices,” Hayden wrote. “I have done this however for what I and some of my senior parliamentary colleagues believe to be [in] the interests of the party.” Hayden outlined the “agreement” in six points:

1. That you will immediately arrange for appropriate employment for all members of my staff who are not currently employed in the Australian Public Service.

2. That you guarantee the continuation in their existing Shadow Ministries or an alternate Shadow Ministry of equivalent status to be agreed upon with them of Messrs John Dawkins, Peter Walsh and Neal Blewett.

3. That I will be appointed as Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs until the next federal election and thereafter in the event of Labor losing such election until such time as agreement is reached on any alternate position between us.

4. That I, as Shadow Minister may be allocated in addition to any staff entitlement I shall have a staff member of Assistant Private Secretary Grade II. entitlement.

5. That in the event of the Labor Party forming a government after the 1983 Federal election, I be appointed as Minister for Foreign Affairs, such appointment to be of such period as is required to enable me to be appointed Australian High Commissioner to London for a period of five years.

6. In the event of the Australian Labor Party not forming a government following the 1983 Federal election the arrangement as referred to in the preceding paragraph is to apply immediately following the next succeeding election if at that election the Labor Party is elected to government.

The principal figure in persuading Hayden to stand aside was Labor’s Senate leader, John Button. After Labor’s failure to win the Flinders by-election in Victoria in December 1982, Button decided that Hayden had to go. They spoke about the leadership in person and on the phone throughout January.

Button stayed with Michael Duffy, the member for Holt, and his family at Kirra Beach on the Gold Coast. Days later, Button would meet with Hayden in Brisbane. It weighed heavily on his mind. At the beach, Button and Duffy went for a swim. Button was thrashing about in the surf. “You’re getting a bit far out there, John,” Duffy yelled out. Button replied: “I’m wondering if I should keep going.”

On January 6, Button told Hayden that he should stand down as leader. Hayden only had an hour to spare because he was busy renovating his bathroom at home. In any event, he would not make way for a “shallow man” like Hawke. To shore up his leadership, Hayden reshuffled the shadow ministry and made Paul Keating shadow treasurer. It was announced on January 14.

Button decided to chip away at Hayden’s confidence, targeting his fatal weakness. Button knew he had to nurse Hayden to the point where he would quit. Another leadership challenge would not work. Hayden had to pull the trigger himself. Button would become both therapist and assassin.

Eventually, on January 28, 1983, Button wrote Hayden a long letter. This letter was Hayden’s death warrant. “I believe that you cannot win the next election,” he argued. “You said to me that you could not stand down for a ‘bastard’ like Bob Hawke. In my experience in the Labor Party the fact that someone is a bastard (of one kind or another) has never been a disqualification for leadership of the party.” Button had tightened the screws. He told Hayden that he must resign.

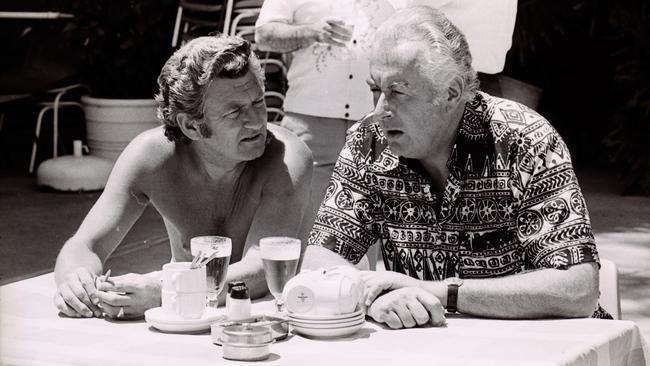

Button was also speaking to Bowen, the deputy leader, about a leadership change. It was Bowen who suggested Button write to Hayden. Button was also speaking to Hawke. Along with Duffy, he met the leader-in-waiting at his Sandringham home on January 16. Hawke rubbed suntan lotion on his skin by the pool as he listened to Button outline the plan. Button said Hayden wanted concessions. Hawke already knew this; he had spoken to Hayden directly.

After Hayden received Button’s letter on January 28, events gathered speed. They spoke on the phone on January 30. On the afternoon of February 1, they talked for two hours in Brisbane. This was when Hayden agreed to make way for Hawke. The plan was that he would resign on February 4, provided Hawke agreed to his conditions. And it would have to be in writing. Hayden was driving a hard bargain. Button updated Hawke the next day, February 2, and told him to get ready to fulfil his destiny.

On the morning of February 3, journalist Laurie Oakes learnt that Fraser was preparing to call a snap election. Fraser wanted to stop Labor changing leaders. Oakes phoned Hayden and told him this might help him hang on. “So that’s what Fraser’s up to, is it?” Hayden replied. He decided to outsmart Fraser by bringing his resignation forward. But he did not know Fraser was planning to drive out that same day to Government House to recommend an election.

At the time, Fraser privately boasted to colleagues that he had a Labor source who informed him that Labor was about to change leaders. According to Fraser’s senior adviser, Alister Drysdale, that source was Neville Wran, the premier of NSW and Labor’s national president. “We got a tip-off from Wran that Labor was about to change leaders,” he recalled. Fraser believed Labor could not change leaders once an election had been called. After all, the shadow cabinet was meeting in Brisbane, and only the Labor caucus meeting in Canberra could change leaders. It was a monumental blunder. Hayden suspected Tom Uren was Fraser’s source but was not surprised to learn it was likely Wran. “If Wran knew, he’d know because Button told him,” Hayden thought.

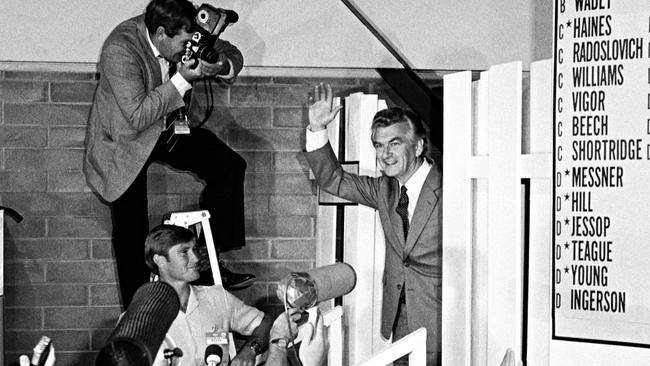

Meanwhile, Hawke and Hayden fronted separate press conferences in the lower ground floor theatre. Hayden was broken-hearted. “I believe that a drover’s dog could lead the Labor Party to victory,” he told journalists. The guillotine fell. He returned to his office and went into the bathroom, locked the door and wept. “It hurt like hell revised several times,” Hayden said.

That evening, Hawke was asked by journalist Richard Carleton if he had “blood on his hands”. Hawke replied that it was a stupid question. It had, in fact, been a bloodless coup. There was no leadership challenge, no faction bosses with a tap on the shoulder and no public demands that Hayden quit. Labor quickly bonded in the ritual of an election campaign with victory in sight.

Hayden’s downfall was ruthless, brutal and sad. But it was the price Labor was prepared to pay for electoral victory. Hayden might lead Labor to power, but the party’s research showed that Hawke would guarantee it. “It wasn’t as though he’d done a bad job, but the question was very debatable as to whether he could win the election,” Hawke reflected. “I was fairly certain I could.”

It was difficult for Hayden to relinquish the leadership. “I was in personal turmoil about stepping down as leader,” he recalled. “I felt like a total failure. It really hurt. But I couldn’t hang on. Malcolm was tough and unforgiving. He would have given me a hard time.” A few days earlier, Hayden had attended the funeral of former wartime Labor prime minister Frank Forde. The Labor Party left Brisbane having buried two leaders.

Hawke’s ascendancy to the Labor leadership, and a month later the prime ministership, was like no other in Australian history. He led Labor back to office with a landslide election victory. Election day was also the birthday of his father, Clem, who had turned 85. “This is the best birthday present you could give me, son,” he said. The intense love of Hawke’s parents gave him an inner confidence. Hawke believed there was a “guiding” presence that propelled him towards the prime ministership, but downplayed notions of divine intervention.

Hawke’s was a life of constant reinvention and redemption. As a kid born in the small country town of Bordertown, South Australia, and growing up the son of a clergyman and a schoolteacher, he had thought about becoming a farmer or doctor. He was deeply religious but his faith was shattered in 1952 during a Christian student conference in India, where he witnessed widespread poverty. Hawke had first seriously thought about public service of some kind when he won a Rhodes Scholarship to commence in 1953. At Oxford University, and later at the Australian National University, he was eyeing a career as an academic.

In 1958 he was appointed the ACTU’s research officer and advocate and 11 years later was elected its president. Over the next decade, he earned a reputation for resolving intractable industrial disputes, led the union movement into several enterprises and became a prominent contributor to political debates. He was the most brilliant, articulate and effective leader the trade union movement had produced. Hawke had found an outlet for his talents. But the question of when he would go into politics percolated through the 1970s. The idea that Hawke could one day be prime minister excited some and repulsed others, but it remained an idea so pregnant with promise that it was fixed in the public mind.

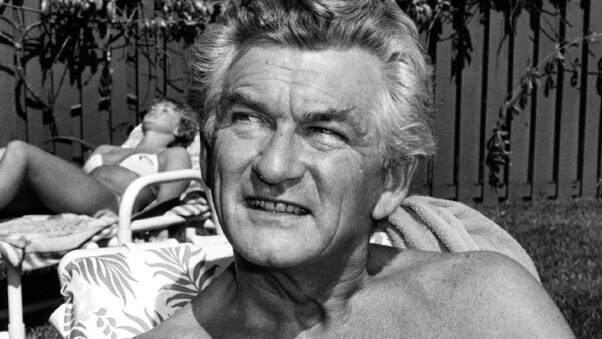

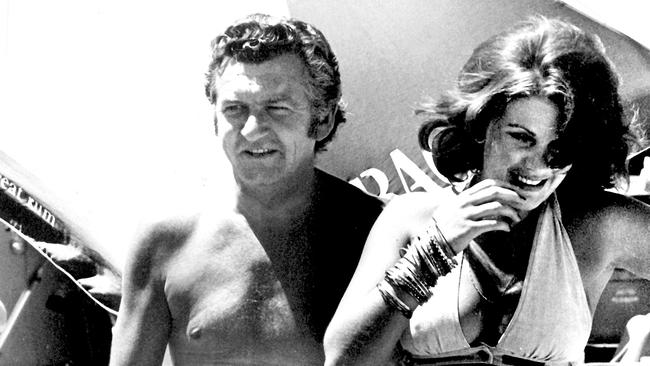

The problem was that Hawke was a notorious drinker, infamous womaniser and prone to angry public outbursts. He was a terrible drunk and could get verbally abusive when inebriated. He was also a serial adulterer. Some women threw themselves at him, mesmerised by his charisma and power, and others he flatly propositioned. When scorned, he would lash out and often humiliate them. He could be selfish and careless. His emotions, whether revealed as tears or temper, were often vividly on display.

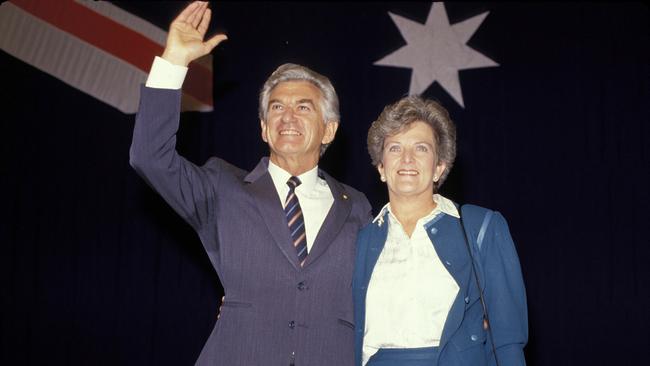

He married Hazel Masterson in 1956 and they raised three children: Susan, Stephen and Rosslyn. They lived with the roiling turmoil that most Australians read about or saw on television, and suffered because of it. Hawke personified the very best and worst in Australians. He was a deeply flawed person, and his behaviour would not be tolerated today. He could be vain and arrogant one moment, and then compassionate and inspiring the next. He embodied a mix of contradictions and contrasts but he was an authentic political leader. He never hid who he was or tried to be someone he was not.

Television was his premier means for talking to everyday Australians. The secret was that he imagined talking to just one person. If you met Hawke, it was like being struck by lightning. The long, wavy, metallic hair, the tanned, soft, olive skin, the arched eyebrow, the mouth with the corners turned down, and the darting eyes with cigar in hand became legendary. He carried himself with an air of satisfaction and projected confidence. At a moment’s notice, like a board being clacked on a sound stage, he could transform to suit the audience. He was a supreme performer who could turn on a range of emotions, as though flicking through index cards until he found the right one: charm, persuasion, indignation, anger, sadness, humour. Voters tuned in because they did not know which Hawke they would get. He entered parliament in 1980. But to succeed in politics, Hawke’s life had to enter yet another phase.

He gave up the booze and stabilised his emotions to become prime minister. But he still had a steady group of women who satisfied his sexual needs. Hawke’s longest affair was with Jean Sinclair, who had become his personal assistant at the ACTU in 1973. It continued during his prime ministership. His affair with D’Alpuget, which had first begun in 1976 and continued while she wrote his authorised biography (published in 1982), recommenced in 1988. “While he was prime minister, there were about four women he was having serious affairs with,” acknowledged D’Alpuget. When Hawke rolled into a capital or regional city, some women would ring his office to let him know they were available. Sometimes Hawke would proposition women, or they would proposition him. Hazel knew about Jean and Blanche, and probably others. “The affairs were, in a way, the least of the worries,” her friend Wendy McCarthy said. “The alcohol mattered more than the affairs. She would not have been happy about it but there was nothing she could do about it. She was resigned to it.”

Hawke did not believe he had an addictive personality. He refused to accept that he was an alcoholic, and would never have accepted that he had an addiction to sex, but D’Alpuget believed he did. Asked if Hawke had a sex addiction, D’Alpuget responded: “I think so. Because sex will calm people down, and he was a very highly strung man. At the end of a day of intense activity, he somehow had to let off steam, as it were, and there’s nothing like a roll in the hay or five to do that.”

Hawke made conciliation the centrepiece of hispitch for the prime ministership. He wanted to “bring Australians together”. The Hawke government was more pragmatic than ideological, and many of its policies were crafted by necessity rather than design. His overarching vision for Australia was to have a more competitive and productive economy and a compassionate society at home, and to be an independent and respected nation abroad. The 1980s was an exhilarating decade. Hawke eschewed class war and the politics of envy and worked with business and unions to turn Australia in a new direction. He saw opponents as adversaries, not enemies. The nation became more confident and optimistic, dynamic and brave, with a renewed sense of identity and purpose in a rapidly changing world. The Hawke government smashed the established policy settings and introduced vast economic, social and environmental reforms.

As longstanding policy pillars tumbled, and Labor agonised over the ritual slaying of its sacred cows, it was rarely smooth sailing. Cabinet and party disputes were frequent but Hawke managed to keep Labor largely united. In doing so, he changed the party. But he also transcended it. He enlarged Labor’s mission, challenged its beliefs and made it fit to govern. He had learnt from the failures of the Whitlam era. Policymaking was invested with rigour and purpose. The public service was encouraged to give frank and fearless advice.

The voters endorsed the Hawke approach with sustained high approval ratings – which reached 78 per cent in 1984 – and four election victories. Hawke was the brightest star in the political galaxy. He assembled and led the finest constellation of talent in the cabinet room that Australian politics has witnessed. He was a strong and purposeful leader, but he was also consultative and collaborative, and unafraid to advance a difficult or unpopular cause or retreat pragmatically when he saw little prospect of success. Hawke, certainly, did not get everything right. But the ledger is overwhelmingly stacked on the side of having made the right decisions when tested, and his legacy stands unmatched by that of any post-war prime minister. In Hawke, Australians saw the mysterious but always recognisable alchemy of political leadership. And that is what should be remembered above all.

Edited extract from Bob Hawke: Demons and Destiny by Troy Bramston (Viking, $49.99), out March 1.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout