Bob Hawke lied about sending forces to Gulf War

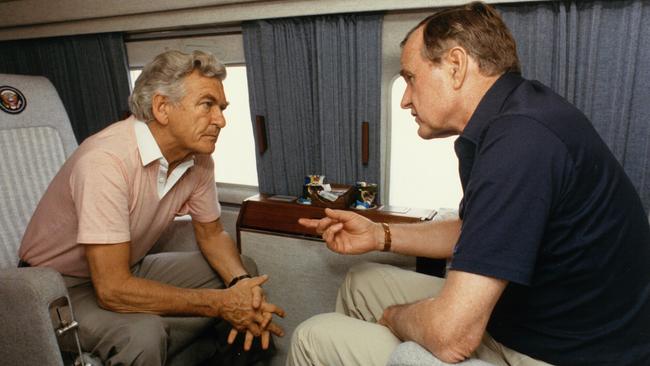

Phone transcripts have finally proved that Bob Hawke lied about the decision to commit Australian forces to the Gulf War in 1990.

Bob Hawke lied about the decision to commit forces to the Gulf War in 1990. There had been no formal US request to help enforce sanctions against Iraq when Hawke offered to send navy vessels and asked George H.W. Bush to say that Australia was invited, rather than Australia invited itself.

Phone transcripts reveal that after Iraq invaded Kuwait, Hawke offered to “send three ships” if the formal request came, following informal talks between diplomats, and asked Bush to guarantee regular consultation and say that the invitation came from the US.

“At the press conference, I can say you will have your people talking with us on a more definite basis as, I understand, participation is concerned,” Hawke told Bush on August 10. “For presentation, you called me, we had a yarn, we will be working (out) participation. We indicated our willingness to be a part of it.”

The US president got the message. “We will say that I called you to request if Australians could participate,” Bush replied. “You were positive. Details will be worked out by others. We will, in seven hours, watch for the take, then we’ll make a positive suggestion.”

But when Hawke announced that Australia would send ships to the Persian Gulf, he said he had not phoned Bush. “President Bush called me this morning,” Hawke claimed. “We agreed that Australia would contribute to a multinational task force in the Gulf.” When later pressed by journalists, Hawke insisted: “No, I did not phone president Bush.”

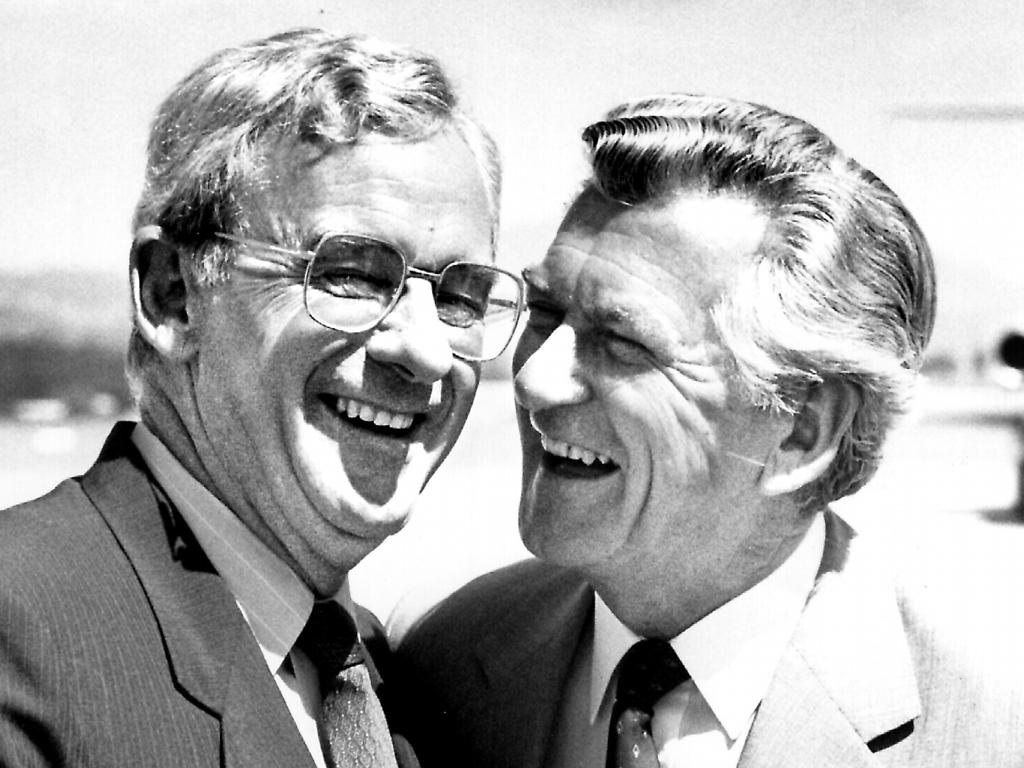

The revelation that Australia invited itself to the Gulf War is in a new biography, Bob Hawke: Demons and Destiny, published by Viking on March 1. The book includes interviews with Bush, Canadian prime minister Brian Mulroney and US secretary of state James Baker, and also excerpts from Bush’s unpublished diary.

Bush did not dispute the sequence of events, said he appreciated the “unwavering” support from Australia and emphasised his friendship with Hawke. Bush and Hawke spoke regularly during the Gulf War.

Earlier, in 1989, Bush noted in his diary that he had “a special relationship” with Hawke.

“The invasion of Kuwait was one of those ‘put up or shut up’ moments for the global community – either you were for the rule of international law, for the defence of a fellow member of the UN and a sovereign nation, or you were not,” Bush said.

“Hawke made a strong, principled stand with the civilised world, and followed through to help right a historic wrong. It meant a great deal to me personally.”

Hawke, when presented with the transcripts, said he was not concerned about being seen as too eager to send Australians to war. He also saw no problem with his decision being made without cabinet endorsement, insisting that prime ministers must be able to exercise their judgment.

“You had a sovereign independent state invaded without cause by a neighbour,” Hawke said.

“If that had been allowed to stand, then the rules of international behaviour would have changed forever, and you could not allow it to happen.”

When Hawke first spoke to Bush, the US president said “there would be great interest in your participating” in a US-led multinational task force to enforce UN sanctions but did not request Australia’s involvement. Hawke made it clear “if the request comes” then Australia would send two frigates and a tanker.

Hawke claimed Mulroney was reluctant to join the coalition because of Canada’s wheat trade with Iraq. Hawke said he persuaded Mulroney, but Mulroney had already told Bush that Canada would participate. “I committed to Bush on 6 August and Canada was the chairman of the (UN) Security Council,” Mulroney said. “Nobody had to talk me into anything.”

In January 1991, after Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein ignored UN resolutions, Australia committed forces to liberate Kuwait in coalition with other nations. Bush told Hawke on January 10, a week before the withdrawal deadline, that he expected war could not be avoided. It began with aerial firepower and then a ground assault.

Bush phoned Hawke to confide his concern about the loss of lives on February 24. “I have worried about it,” Bush told Hawke. “The loss of ground troops is on my mind. I hope it will be quicker than people’s predictions, with fewer casualties.” Within days, Iraq was defeated and expelled from Kuwait’s borders.

Hawke claimed that Bush was pressured to send forces to Baghdad and remove Hussein from power, and he counselled against this. Bush disputed this: “The idea of going to Baghdad in that situation was not on my mind.”

Baker, the then US secretary of state, said Hawke was mistaken. “Not one of Bush’s aides (or) top people – secretary of state, defence, CIA – argued that we should go to Baghdad,” he said.

“Bob was wrong if he thinks there was a debate within the US administration at the time about going to Baghdad.”

Baker, who also served as White House chief of staff under Bush, said of the Bush-Hawke relationship: “They were very, very close … we had no better friends than our Australian allies.”

Troy Bramston is the author of Bob Hawke: Demons and Destiny (Viking) published next Tuesday

Tomorrow in The Weekend Australian: Read more coverage and an exclusive chapter

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout