Keating: art and the artful

Paul Keating, first elected to parliament 50 years ago, is a national icon.

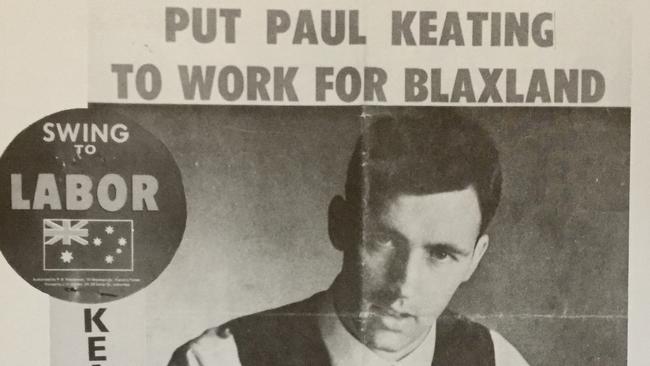

At just 25, he represented the safe Labor seat of Blaxland in Sydney’s western suburbs. Some MPs, such as Arthur Calwell and Fred Daly, had served in parliament since before he was born.

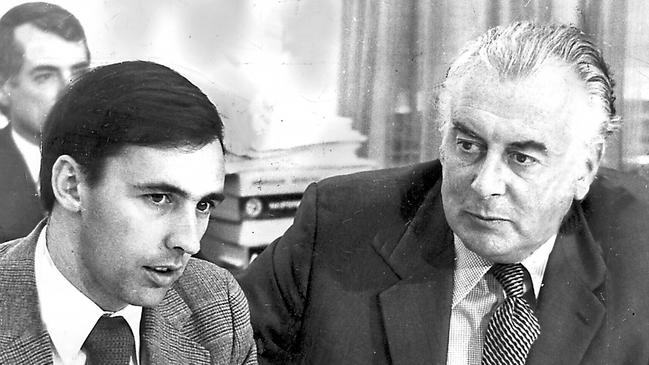

But Keating, ever ambitious and eager to make his mark, was unfazed. He quickly understood that politics was a learning profession. He studied John Gorton and Gough Whitlam, sought out public servants such as Sir John Bunting and introduced himself to journalists such as Max Walsh, Alan Ramsey and Fred Brenchley.

“They thought I was pushy and they thought right — I was,” Keating, 75, says in an exclusive interview. “I was interested in older guys like Clyde Cameron, Frank Crean, Kim Beazley Sr, Rex Connor. I was interested in their distilled wisdom. They didn’t quite know what to make of me but I think they detected something in me that was attractive to them.”

Keating remembers walking up the steps of Old Parliament House and stepping into Kings Hall for the first time as a newly elected MP. He was wearing a smart three-piece suit, carrying a gold fob watch and his shoes were so shiny he could see his reflection in them.

“The impression one had was the intimacy and closeness of it all,” he says. “There would be Alan Reid from The Daily Telegraph hanging over a glass case, which had the Constitution in it. He would be having a smoke and he could have just as easily been talking to Kim Beazley Sr. It was that sort of a place.”

He describes what it was like sitting on the plush green leather benches in the old House of Representatives chamber. “No matter where I sat, I was within 15-20m of the prime minster,” he says. “So you were watching the facial movements, the mannerisms, and the difficulty of the questions or the ease of the answers. You were right there.”

Gorton had succeeded Harold Holt as Liberal leader and was sworn in as prime minister in January 1968. The Liberal and Country parties had been in power since December 1949 and suffered a huge swing against at the most recent election.

“Gorton’s decency and directness were the central reasons why he defeated the Whitlam opposition in 1969,” Keating says. “Had (Billy) McMahon or Holt been prime minister, Whitlam would have beaten them. But Gorton was an affable and knockabout sort of fellow, and I think that saved the Coalition.”

Keating learned that parliament was where a prime minister drew their authority. It was essential to dominate and win debates. He recalls Bunting telling him: “Holt died a thousand deaths at every appearance at question time and hung on to his brief like it was a life vest.”

He also recalls watching “very sadly” as Gorton’s position declined and Gorton was replaced by McMahon after a confidence motion in his leadership was tied 33-all in the Liberal partyroom in March 1971. Keating thought the government was in its “death throes”.

“The public service was running the country,” he says. “This was the age of the incrementalism when ministers were happy to have the black cars and the word ‘Honourable’ in front of their name, and the real power was the bureaucracy. But the bureaucracy lacked policy ambition.”

Meanwhile, Labor was resurgent. Whitlam had succeeded Calwell as Labor leader in February 1967 and set about reforming the party’s structures, rejuvenating its policies and recruiting new candidates. “Gough was majestic in his own way,” Keating recalls. “He had a great presence and a great command of the parliament, a great sense of humour.”

Keating had won a difficult preselection in October 1968. He defeated five other candidates including the sitting member, Jim Harrison, and the main challenger supported by Labor’s Left faction, Bill Junor. The preselection vote was disputed and, amid allegations of rorting from both sides, Keating was officially declared the winner a week later. He was 24.

“You had to get out of bed early in the morning to do that, I can tell you,” Keating says.

“But I understood the drumbeat of the branches. I had been president of the Youth Council of the party and I’d been attending state conferences. I developed the skills of persuasion: being able to tell a story and make ideas stick.”

He quickly developed friendships and alliances in caucus. He initially shared a small office with Lionel Bowen — L.96. He remembers staying at the Kurrajong Hotel where MPs from all parties would eat breakfast together in the morning and reflect on the day’s events over dinner in the evenings.

In caucus elections for the Whitlam ministry in December 1972, Keating missed out by just one place. The Whitlam government, he says, was “chaotic” but turned Australia in a new direction. “The Whitlam government had a social and an international strategy, but it had no economic strategy,” he says.

In October 1975, Keating was made minister for northern Australia, just weeks before the government was dismissed by governor-general Sir John Kerr. The blocking of supply in the Senate, which precipitated the dismissal, injected a poison that eroded comity between MPs.

“The goodwill between the parties evaporated and it never returned,” Keating says.

Bob Hawke was elected ACTU president in the month before Keating was elected to parliament. Together, as Hawke said, they were Australia’s “greatest political duo”, who transformed the economy in the 1980s before their relationship soured and they fought a battle for the Labor leadership in 1991.

“Bob and I came into parliament from different directions but we had a similar view about the way Australia had to go,” Keating says. “When the Hawke government was elected we had falling real terms of trade, double-digit inflation, double-digit unemployment and a massive loss of competitiveness with very high tariffs.

“The only two people in the Labor Party from the outset that believed the closed way was the wrong way for Australia was Hawke and me. My job as treasurer (1983-91) was to dismantle the Deakin legacy — that was a big technical and persuasive job — but I had the intellectual support of the prime minister.”

Keating recalls his relationship with Hawke. “It was very, very close,” he says. “I was treasurer to Bob for 8½ years. Julia Gillard moved against Kevin Rudd after 2½ years.

“I was there with Bob through eight budgets and economic statements. There was a high level of co-operation and friendship right throughout until those last months.”

The economic reforms were groundbreaking: floating the dollar, dismantling the tariff wall, financial sector deregulation, slashing company and personal tax rates, asset sales and delivering four budget surpluses — the first since the 50s. The 1990-91 recession, however, takes some of the shine off these achievements.

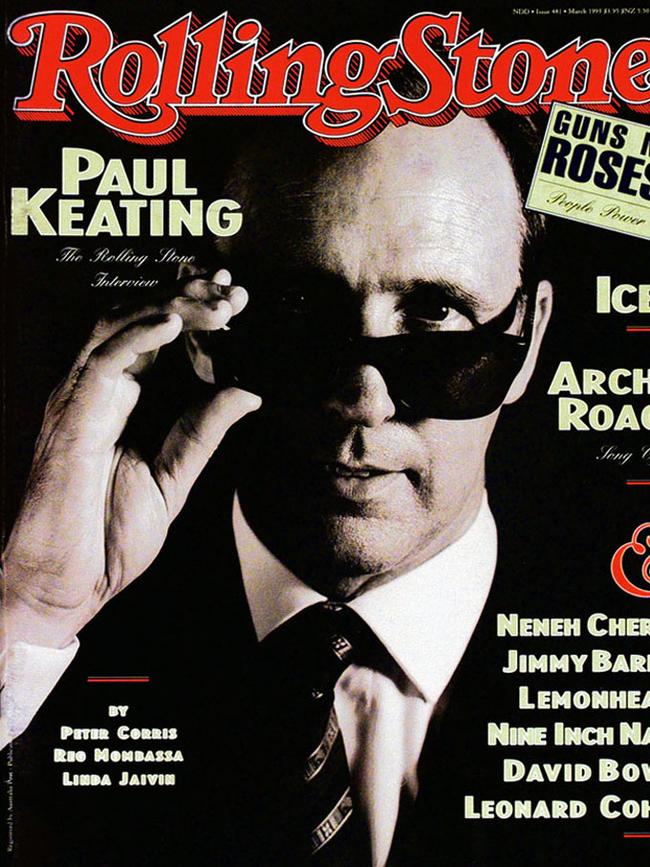

Keating served as prime minister from December 1991 to March 1996. The economic reforms in these years — superannuation, competition policy, trade liberalisation and enterprise bargaining — are often overlooked. He is proud of delivering the Native Title Act, putting the republic on the agenda, championing the arts and establishing the Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation leaders meeting.

Although reluctant to discuss Labor’s election defeat in May, Keating believes the party’s policies had virtue but were seen by many voters as a big-taxing and big-spending agenda. He worries that Labor has veered away from the model of government he pioneered with Hawke in the 80s and 90s.

“People don’t want to be given things off the budget, to become a welfare recipient or a subsidised person, they want the freedom to achieve in their own right,” he says. “The Labor Party should be alert to the aspirations of the people. By aspiration I mean giving people the tools to run their own lives and to make their lives more satisfactory and happy.”

As a young man, Keating was on a quest to understand what he calls “the ends of power” — how it is gained and how it is used. This was often what he discussed with Jack Lang, the elderly former NSW premier, in the 60s and 70s.

He names three things a successful politician must have: a core set of beliefs, determination and drive, and the ability to persuade.

“If you can’t imagine a new economic landscape, if you can’t imagine a new social landscape or an international one, there is no way you are going to get one,” he explains. “In the end, if the creativity is not there, if the artistry is not there, the output will look meagre and dull, which is what it mostly looks like these days.”

Keating encourages politicians to have broad interests. He has a world-class collection of artworks, antique objects and furnishings, which he has been assembling since he was 15. These things, much more than clocks, reflect the dawn of the modern political age that began after the French Revolution in 1789.

“It is a testament to the attempt by the French society to create a democratic order, a return to the values of Republican Rome 2000 years earlier, reflecting justice, freedom, the rights of man,” he explains. “The collection of things I have are a philosophic collection; they are not a bunch of trinkets.”

Music remains another abiding interest. “If you let the great composers take you, then your mind starts to turn creatively and you end up doing better things and dream better dreams,” he says. “I’ve often said I remodelled the Australian economy with my two best friends, Mr Bruckner and Mr Mahler.”

It is not surprising the one talent Keating wishes he had is to be able to conduct a great symphony. “I would love to be able to stand up and confidently do all the Bruckner symphonies, all the Mahler symphonies, Shostakovich, Elgar, Brahms and, if I was stretching it, a Wagner opera,” he says.

Keating does not like to dwell on the past; he prefers to focus on the future. He says “the big picture” for policymakers today is the shift of power and wealth from the Atlantic to the Pacific. In a new era of “great power rivalries” he says Australia should position itself as “a balancing power”, confident of its own place in the world and without having to choose between the US or China.

“I’ve always believed that the world is of its essence an anarchy,” he says. “We are seeing a return to great power politics, which was not part of the collaborative model the Americans administered post-1947 or what we are seeing in Europe, where sovereignty is granted to a central power. I think multilateralism, though laudable, runs against the long currents of history.”

The other transformative change is that people are more globally connected because of the digital revolution. This means the economy and society are more horizontally structured rather than the silos that prevailed in business, society and politics he experienced when he left school at 14. “We should be pulling together the important threads and struts of the vocational education system,” he says. “Modifying our education system to allow young people to swim their way more confidently in the much more horizontal and collaborative world that the digital economy facilitates.

“In the great Japanese houses, you often see they have a shallow pool with many fish swimming around. We are moving into a world like that, a shallow but wide pool of connectivity, and we have to teach young people, especially, to be able to swim … and to find the opportunities in that pool.”

If Keating did not go into politics 50 years ago, he was well placed to work for his father’s successful concrete businesses. But this would not have delivered the ultimate reward of public life: public progress. “Though I could have had a commercial life, the one and only highwire is public life,” he says.

Troy Bramston is the author of Paul Keating: The Big-Picture Leader (Scribe).

When Paul Keating was elected to parliament 50 years ago — on October 25, 1969 — he was the youngest MP.