Robert Menzies model is key as Liberal Party tries to find pathway back to power

Four former PMs look to the past for a survival strategy to help their depleted party.

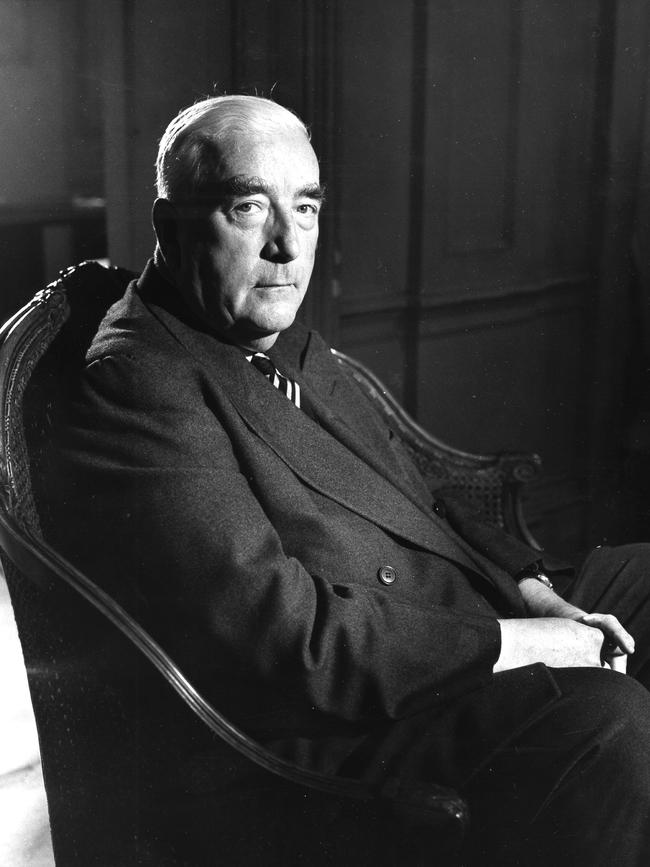

It was essential, Menzies argued, that the party adopt “a liberal and progressive faith” that supported “political and economic progress”. It would not be a reactionary conservative party that was simply a “critic” of Labor. It would be positive, forward-looking and innovative in its policies and ideas.

“There is no room in Australia for a party of reaction,” Menzies said. “There is no useful place for a policy of negation.”

This elemental character of the Liberal Party, as conceived and advocated by its principal creator, could not be more relevant today as it faces its greatest crisis. In 2023, the Liberal Party is out of power on the entire Australian mainland. Over the past decade, the party has ceded safe federal and state seats to Labor, Greens and independents. The loss of the Melbourne seat of Aston in April 2023 was the first time an opposition had lost a federal seat to the government at a by-election in more than a century.

The party has suffered the long-term loss of votes from young people, women and migrants. It may be comforting to think current circumstances resemble the post-defeats of 1972 or 1983 or 2007, and that recovery will come soon enough. But this is not a cyclical moment. This crisis is existential, and the party’s survival is not guaranteed.

The defeat of the Morrison government in May 2022 exposed the extent of the challenge. It was a political earthquake. The loss of heartland seats such as Kooyong, Goldstein, Curtin, North Sydney, Mackellar and Wentworth to so-called teal independents, along with Higgins, Bennelong, Tangney, Pearce and Boothby to Labor, represented a revolt from the party’s base.

The seats of Kooyong, Higgins, Mackellar and Boothby had been won by the Liberals at every election since 1949. Tangney was last won by Labor in 1983, while Goldstein had been Liberal since its creation in 1984, as had Pearce since its creation in 1990. The seats of Ryan and Brisbane were lost to the Greens.

Along with Warringah, lost in 2019, these constituencies were the reliable affluent, educated, professional, small-l liberal middle and upper classes that had been the backbone of the party. It is where most of the party’s members and donors live. It leaves the Liberal Party in search of a constituency.

If the party cannot regain the seats it has lost to the teals, it will be almost impossible to return to government, in coalition, with a majority of seats.

The party must develop an agenda that appeals to voters in seats they once held. Moreover, it must be a coherent Liberal agenda that targets three opposing political ideologies: from Labor, the Greens and the teals. This will not be easy.

In his “Forgotten People” broadcast of 1942, Menzies spoke of voters who were in the middle ground but politically homeless. They were not “rich and powerful” or “the mass of unskilled people”, but somewhere in the centre ground, “unorganised” and “unselfconscious”, who needed a party to represent them. This became the creed of the Liberal Party.

Menzies made a direct appeal to “professional men and women”. He sought to represent the educated, community-minded, progressive middle class with deeply held moral values. Many have now found a home with Labor, the Greens and independents.

To lose Menzies’ Kooyong, also held by Andrew Peacock, at the last election is a body blow. But 11 of the 14 seats held by former Liberal leaders are now lost.

The Australian Election Study revealed Labor to be grappling with many of the same challenges as the Liberal Party regarding its identity and constituency. While Labor has lost seats to the Greens, it has successfully been able to straddle different constituencies – one blue-collar, many of whom are socially conservative, and the other more wealthy, progressive, post-materialist – and win enough seats to form governments. But its primary vote has also declined as tribal loyalties have eroded and party dealignment has accelerated.

The AES showed the Coalition is bleeding support from under-40s and under-50s. Just 25 per cent of millennials (born 1981–96) and 26 per cent of Generation Z (born 1997–2012) voted for the Coalition. Just 32 per cent of women backed the Coalition. Demography is working against the Liberal Party. It cannot rely on the ageing, often conservative, greying baby boomers (born 1946–64) who are outnumbered by millennials and Generation Z.

Most of Generation X (born 1965–80), along with millennials and Generation Z, do not identify with the Liberal brand. They characterise the party as representing older voters, in denial about climate change, hostile to women, against diversity and inclusion, weak on integrity, obsessed by culture wars, and out of step on Indigenous constitutional recognition and republicanism.

The 2022 federal election, and a slew of state elections, reflect deeper troubles that go to the Liberal Party’s identity, purpose, candidates, constituency, and campaign capacity. The party lacks an animating and unifying brand and mission to rally behind, and is often defined by what it is against rather than what it is for.

Menzies gave voice to a new party that would champion greater individual freedom, personal choice, and enterprise. He spoke of a party that would promote security, opportunity, and prosperity for all. It had a clear and purposeful political identity that acted as a lodestar to navigate by.

The party has always had liberal and conservative wings, but the former has now been largely squeezed out. The broad church was once an article of faith. Past leaders such as Malcolm Turnbull, John Hewson, Peacock and Malcolm Fraser found it hard to identify with the modern party, which has become more conservative. It is no surprise that many small-l Liberals now vote teal.

Menzies designed a party with mass membership that reflected everyday Australians, was not captive to outside groups, and had grassroots community links, and where women were equal to men.

Indeed, the Australian Women’s National League sent representatives to the twin conferences that Menzies convened in 1944, and merged with the Liberal Party in 1945.

Yet today, the Liberal Party has seen women desert it in droves – the party’s official review following the 2022 election defeat found that it had “performed particularly poorly with female voters”. It is a trend that began two decades ago and now a majority of women in all age segments prefer Labor.

Menzies also wanted a party that could attract candidates from a diversity of backgrounds with different life and work experiences. Instead, today’s Liberal candidates are too often drawn from narrow fields such as political staffers, party officials or lawyers.

The party at both state and federal levels has become heavily factionalised and less democratic, and its campaigning capacity has diminished.

The party had 150,000 members in the 1940s and 200,000 in the 1950s; they now number fewer than 30,000.

The party needs to rediscover the Menzies model to be a truly representative party that is in touch with contemporary mainstream thinking.

Menzies invited 77 men and women representing 18 centre-right organisations to the Canberra conference in 1944 that he later identified as the birthplace of the Liberal Party. Some were sceptical, others were optimistic, but all were in no doubt about the gravity of the challenge.

The United Australia Party had received just 22.4 per cent of the vote at the August 1943 election. John Curtin’s Labor Party had crushed the opposition, leaving them with just 14 out of 74 seats in the House of Representatives. The UAP was finished.

The question for the Liberal Party is also to ask whether it can once again be a broadbased, representative and philosophically coherent force able to win elections (in coalition with the National Party) and sustain itself in power for long periods.

While the recuperative powers of political parties have often been underestimated, those who ignore or downplay the scale of the present challenge are consigning the Liberal Party to history.

Heather Henderson, daughter of Sir Robert and Dame Pattie Menzies, remembers her father working tirelessly to create the Liberal Party. He had a clear idea of whom the party represented, what its values were, and what it wanted to achieve.

“My father and others went around and spoke to people who ran different organisations that were all more or less on the same side, and he got them all together and made it into one party – the Liberal Party – and now I can see it all gradually getting broken up,” Henderson told me after the last federal election.

Her father rejected the name “conservative” to describe the party. Menzies did not want to create a conservative party; he sought a revival of liberalism.

“I get very tetchy when people refer to it as the conservative party, because that is one thing that he said it was not,” she recalled. “He wanted to create a party that was liberal and forward-looking.”

The Liberal Party has had nine prime ministers. The past four discussed the future of the Liberal Party, its policies and philosophy, organisation and constituency, and lessons to be learnt from its principal founder, in new interviews with me earlier this year.

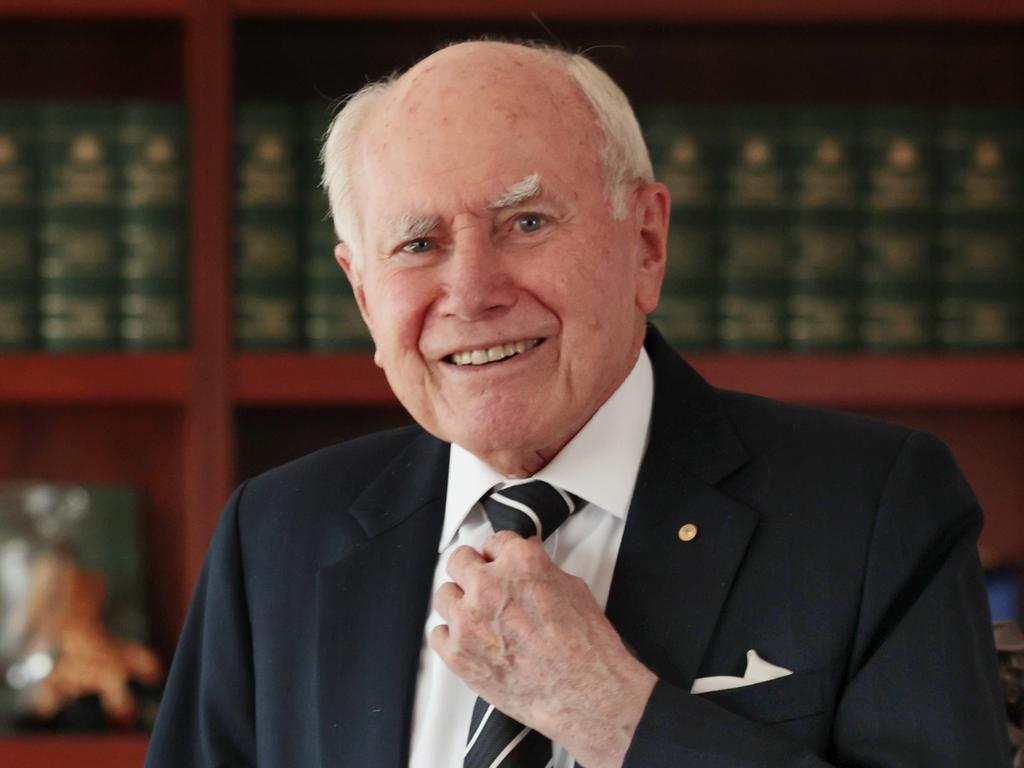

The former prime ministers see Menzies as being a historical touchstone. “He founded the party, overcame the doubts about him as an opposition leader, and led them back into power,” John Howard says.

Menzies played a key role in developing the party’s philosophy, policies, structure and culture.

Turnbull says Menzies was “a builder of coalitions”, and that this remains relevant today. “The Liberal Party itself was a patchwork of many organisations,” he says. “He was the architect of an avowedly broad church.”

Scott Morrison says that although the groups were diverse, they could rally behind a guiding philosophy. “(Menzies) was able to create a political movement that they could support and therefore create a government that was far more mainstream and not captive to any sectional interests,” he says. Morrison adds that maintaining a “cohesiveness across such a spectrum of political views” on the centre-right was difficult then, but is even more difficult now.

In 1944, Menzies had one goal: to create a party fit for purpose. It was designed to win elections and to govern effectively. It had to be both practical and pragmatic while also being guided by values.

“I consider (Menzies) to be one of the most pragmatic politicians to have ever bestrode the political stage,” Morrison says.

Menzies had learnt from his earlier period as prime minister. Especially critical were his relationships with MPs. “He understood the importance of party unity, and he also understood the importance of a strong coalition with the National (Country) Party,” Tony Abbott says. “These are enduring lessons that all successful leaders must heed.”

But there is a risk that the Liberal Party does not have an identity sufficiently different from the National Party. The Liberals have often been perceived as following the Nationals, such as on Indigenous constitutional recognition, or beholden to it, such as on climate change. Menzies had an effective partnership with Country Party leaders, but it was always understood which party was the senior partner and who was the prime minister.

Menzies’ values and philosophy have been interpreted differently. The four prime ministers subscribe to a party that includes a broad church of views and that positions itself in the mainstream centre ground of politics.

Howard does not believe that the party should, as some right-wing commentators suggest, move to the right. That is a political dead end. “I don’t call it a conservative party,” Howard says. “The Liberal Party will only succeed if it successfully presents itself as a broad church.”

Abbott views Menzies in the same way. “Menzies was an orthodox liberal-conservative – liberal on some things, conservative on others – but always in the party mainstream,” he says.

Morrison characterises Menzies as “personally conservative” but not “an extremist” or “an ideological warrior”. Such a leader would not be in the Menzies tradition, Morrison says. “Menzies’ instruction was to connect with the mainstream of Australia,” he says. “That’s why it was successful.”

Turnbull notes that Menzies “went to pains” not to describe the Liberal Party as “a conservative party” and anchored it in the centre ground, between big-business establishment politics on the right and the democratic-socialist tradition in Labor and the union movement on the left. He believes Menzies conceived of and led a liberal progressive rather than reactionary conservative party. “There is today very little room for liberals, and that is showing up in the electoral results,” Turnbull says.

Howard notes that liberals and conservatives agree on the importance of the individual over the collective, the rejection of union dominance in industrial relations, and a preference for lower taxation and less spending. “The Liberal Party should not fall into the error of having an internal debate about ideology every time it has a setback at the polls,” Howard says.

Fewer people are joining organisations: sporting clubs, civic groups, churches, unions and political parties. Both major parties have a narrower pool of talent to draw upon as candidates. “Now you have a whole cohort of people who never do anything other than politics,” Howard explains. “It means the internal dynamic of the party is shaped by this cohort.”

The result is that the party is not as representative of the electorate as it once was. This impacts on its electoral fortunes. “When I joined the Liberal Party in Wentworth in 1973, it was very much a cross section of the middle and professional class of that area,” Turnbull recalls.

“There were QCs and local solicitors, Macquarie St surgeons and local GPs, captains of industry and local shopkeepers, and so on. It felt very broadbased.”

Howard says Menzies “ordained an implied covenant” to guide the party’s parliamentary and organisational wings. “And that is that the parliamentary party should be completely independent and free from outside influence when it came to policy,” he says. “But when it came to organisational matters, such as the choice of candidates, then the party organisation should be completely independent. Now, I think it would be a good idea if a lot of people in the Liberal Party remembered that. There should be greater respect given to the rank and file, if I can borrow a Labor expression, in choosing candidates.”

Abbott is also critical of how the party wing has treated members, and of the rise of factionalism. “All too often, the party looks like an insiders’ club that wants to keep outsiders – everyday citizens who normally vote Liberal and respect the party of Menzies and Howard – at arm’s length,” he says. “If the existing members can’t be trusted to get preselections right, (then) appeal for more members – don’t override the ones you have.”

Morrison says the party actively discourages new members because of the way it operates. “The party’s structures, it’s constitution, all of this, is kryptonite to the type of people that we are trying to reach and be part of our political movement,” he says. The party has to find new ways to connect with the community. “The system no longer is fit for purpose,” Morrison adds.

Just who exactly the Liberal Party should and does represent is a matter of debate. As noted, the party has lost votes from women, youth and migrants. Turnbull warns that a drift to a right-wing populist agenda, as advanced by some commentators, would doom the party. “Many people in the Liberal Party regard that constituency as being the party’s ‘base’ – it is not,” he says. “The base of a political party is best regarded as those who habitually vote for it and that base is being rapidly diminished.”

Many of the lost voters would have identified as Menzies’ “forgotten people”, “Howard battlers” or Morrison’s “quiet Australians”. Abbott sees these voters as key: “The small businesspeople, the tradies, the people who ‘have a go’ and want the government to respect their efforts, all the people who aspire to do better but who don’t have powerful backers or the resources to be indifferent to government policy.”

Morrison says the party must represent “those who don’t expect the government to run their lives, and do take responsibility and accountability for their own lives, and do feel a sense of responsibility to those around them”.

He accepts the party cannot return to power unless it regains once blue-ribbon seats lost to teals, the Greens, and Labor. “You don’t form government again unless you have representation in those areas in either a coalition or some other form,” Morrison says.

In the final analysis, Howard says the Liberal Party must represent a cross-section of the community.

“It represents aspirational people,” he says. “People who believe that if you work hard, you get success. They believe in private enterprise and in parental choice when it comes to the education of their children. They believe that the welfare state, if I can borrow that expression, should be subject to means testing, and (that) we should look after those who need help. And they are fundamentally people who believe Australia is the best country in the world.”

There is much the Liberal Party can learn from Menzies, even though he governed in a different era. He, too, faced the challenge of revitalising a political movement, making it electorally viable, and leading it successfully in office. Understanding who Menzies really was, what motivated him, what he aimed to achieve, his successes and failures, and how he mastered the art of politics was my motivation behind writing this book. And it is essential if the Liberal Party is to locate a Menzian pathway back to power.

This is an edited extract from the new preface to Troy Bramston’s Robert Menzies: The Art of Politics, republished by Scribe on August 15.

When Robert Menzies addressed a conference convened to discuss the formation of a new centre-right political party at the Masonic Hall in Canberra on October 13, 1944, he spoke of the urgent need to revitalise the non-Labor forces with a “nationwide movement” to defend and promote “democratic liberalism”.