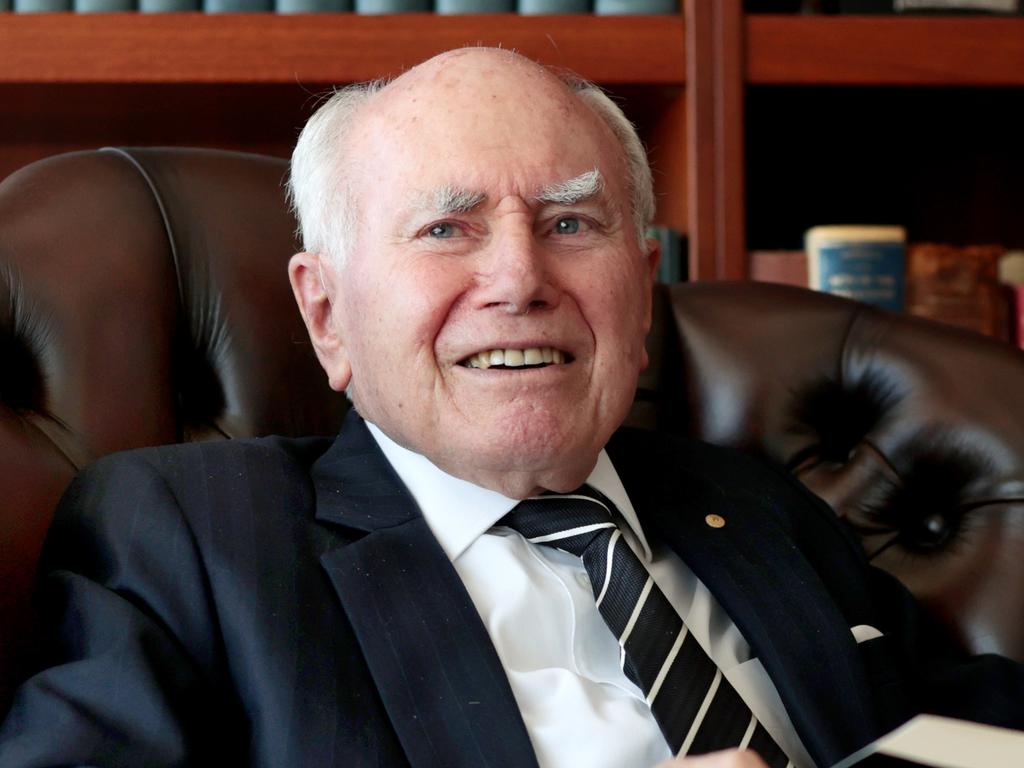

Lessons in leadership from John Howard, 50 years after his election to parliament

In the 50 years since John Howard was first elected to parliament on May 18, 1974, politics has changed profoundly. What does it take to succeed?

“Fewer people in politics have causes today, and that’s a negative,” Howard tells Inquirer. “Part of the explanation for the leadership turmoil in parties is that too many people who are involved in politics see it as a game.”

But Howard would still encourage people to pursue a career in parliament – with one caveat. He says having a diversity of life and work experience will make for better politicians with sharper judgments about politics and a better understanding of policy issues. He wants politics to again be a battle of ideas, values and philosophies.

“A lot of people come and see me and say, ‘I’m interested in politics and have you got any advice?’ And I say, ‘Well, do something else for 10 years. Doesn’t matter what it is and try to make it non-political.’

“These people who think that you are getting corporate experience by being in government relations at a big company are kidding themselves.”

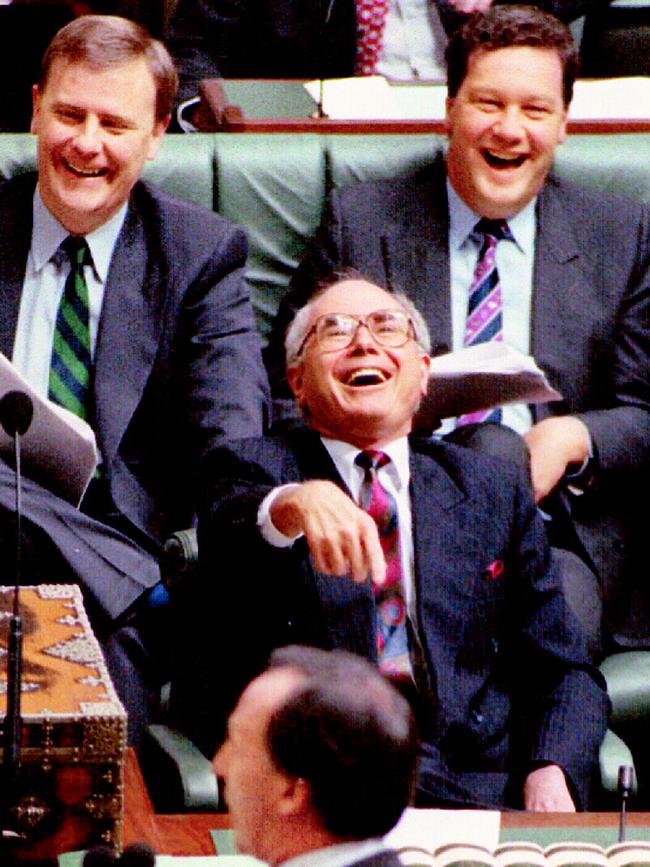

In a revealing interview with Inquirer, Howard reflects on his long career in parliament, as backbencher in the Whitlam government and treasurer in the Fraser years to his frustrating opposition leadership during the Hawke-Keating era, and Lazarus-like return to become the second longest serving prime minister.

In this, my 24th interview with Howard over the past 10 years, he also outlines the essential elements of leadership coupled with the skills required to succeed as a long-term politician and prime minister.

When Howard was a final-year student at Canterbury Boys High School in 1956, he nominated three occupations he could imagine pursuing: journalist, police detective and lawyer. In the late 1980s, after losing the Liberal leadership, he wrote columns for The Australian. “I thought I made a reasonable journalist,” he says.

After earning his law degree from the University of Sydney in 1961, Howard began working for Stephen, Jaques and Stephen. After a round-the-world trip and campaigning for the Conservative Party in London in 1964, he joined a firm of solicitors that would later be named Truman, Nelson & Howard.

“Because of my imperfect hearing, I accepted fairly early on that any ambition I had of going to the Bar had to be put aside because I felt that judges get aggravated enough, but they get particularly aggravated with a half-deaf barrister,” Howard says. “Had I not gone into politics, I would have remained a lawyer.”

One of the first lessons Howard thought vital to politics was managing paperwork. The administrative task of the prime ministership is essential but unobserved by voters. The best prime ministers knew how to keep the flow of paperwork going, whether cabinet documents, minutes, briefs or correspondence. It is a sign of an orderly and focused prime ministership.

“Part of the job is not only to deal in depth with big issues but also to keep the desk clean,” he says. “Unless you can process the routine stuff, they become urgent. And that was obviously the difficulty that (Kevin) Rudd found. One of the skills that being a solicitor teaches you, as distinct from a barrister, is handling paper in an orderly and expeditious fashion.”

Howard had been elected to the NSW Liberal executive and was Young Liberal president. He managed Tom Hughes’ campaign for the federal seat of Parkes in 1963. He met his hero, Robert Menzies, at the Lodge in 1964. He remembers Menzies mixing a martini, dropping an ice cube and chasing it across the floor, picking it up and plonking it into his drink.

Determination is a Howard trait. He won Liberal preselection for the state seat of Drummoyne ahead of the 1968 election but lost to Labor’s Reg Coady. Ahead of the 1972 federal election, he lost the preselection contest for the seat of Berowra to Harry Edwards. On his third attempt to enter parliament, Howard won preselection for the federal seat of Bennelong, and then the seat in 1974.

It was self-belief and resilience that sustained Howard – both are essential in understanding his political career. He is one of the great survivors of Australian politics, serving two periods in opposition and two periods in government.

But his period as opposition leader from 1985 to 1989 was a largely unhappy one and many thought he would never reach the prime ministership. With Howard trailing Bob Hawke in the polls, The Bulletin famously asked: “Mr 18% – Why on earth does this man bother?”

He had been deputy leader to Andrew Peacock and unexpectedly succeeded him in 1985. But the Coalition was divided by the “Joh for PM” campaign, there were personality and policy differences, and Howard lost the 1987 election to Hawke. In 1989 he was the victim of a surprise coup by Peacock supporters.

“After I lost the leadership in 1989, I believed I could still have an influence,” Howard recalls. “I had policy interests and I had invested a large part of my life in politics. I hoped the Liberals would win in 1990, but I had doubts about whether we were equipped to handle the economic debate. And then I was surprised in the end that we lost in 1993, even though the polls had started to go bad.”

The Liberal Party had turned back to Peacock and then overlooked Howard again when it elected John Hewson as leader in 1990, and overlooked him again when it chose Alexander Downer to lead them in 1994.

Howard could be forgiven for thinking his time in politics had gone. After all, he was the one who said returning to the Liberal leadership would be like “Lazarus with a triple bypass”.

Yet Howard remained influential in industrial relations and economic policy debates, and was a good parliamentary and media performer.

“I just stuck around,” he says. “I thought, who knows what will happen? I still had an ambition. I didn’t think I was not up to the task of becoming leader again. I thought I could do the job. I still had enough self-belief.”

When Downer faltered, the party returned Howard to the leadership in 1995. He notes he had become leader by accident, lost the leadership by ambush and returned as leader with consensus. Howard went on to defeat Paul Keating’s government in a landslide election result in 1996.

In approaching the Liberal leadership a second time, and the prime ministership, Howard had accumulated knowledge about politics and government that would underscore his longevity.

In addition to administrative talents and managing paperwork, the first lesson is being able to communicate and persuade. “You should not be in politics if you cannot argue a case,” Howard says. “It amazes me what poor communicators many senior politicians are.” Howard says Gough Whitlam was “the greatest parliamentarian” he saw and it gave him authority.

Second, people management. “It requires constant attention,” Howard says. “There’s no substitute for interaction with colleagues.” He acknowledges being “too tribal” in his first stint as leader and had to be more collegiate and consultative. He would often take lunch in the Parliamentary Dining Room to talk to MPs and his office was always accessible.

His government also benefited from continuity in senior positions: Peter Costello as treasurer and Downer as foreign minister. Howard also pays tribute to the co-operative approach of Nationals leaders Tim Fischer, John Anderson and Mark Vaile. They too understood the art of coalition.

Howard thought it was “unnecessary” and “unwise” for Scott Morrison to swear himself into five ministries without telling ministers, his party, the parliament or voters. Blindsiding colleagues like this is unthinkable.

The third lesson is stamina. Prime Ministers need to be able to manage a big workload, long hours and pressure. “You will not, or you should not, get to the top unless you’ve got stamina,” Howard says.

He took regular naps. He walked every morning for exercise and to clear his mind. It was part of a routine, which included an alternating breakfast of soft-boiled eggs or cereal. He allowed one exception: baked beans on toast on Saturdays. And when making difficult decisions, he sometimes prayed.

Howard also learned from his time as minister for business and consumer affairs (1975-77) and treasurer (1977-83) in the Fraser government. He was just 36 when he became a minister and acknowledges the opportunity that Malcolm Fraser had given him.

But he also took on board lessons from the Fraser years. “Don’t pursue crises; they will happen anyway,” he says, laughing. “Malcolm was not happy unless there was a crisis.” Howard also thought Fraser called too many cabinet meetings without much notice but was in awe of his “mastery” of cabinet paperwork.

Another moral: don’t be consumed by bitterness. Howard appointed longtime rival Peacock as ambassador to the US. Fraser had become a sharp critic of Howard. But Howard tested the waters about a diplomatic appointment. He had in mind high commissioner to South Africa. Fraser, semi-retired, was not interested.

In addition to winning four elections, Howard is especially proud of national gun laws in response to the Port Arthur mass shooting in 1996; sound economic management that expanded the economy, reduced unemployment and raised living standards; delivering 10 budget surpluses; and introducing the GST in 2000.

All prime ministers would do some things differently in hindsight. Howard nominates the delayed response to the High Court’s Wik decision in 1996; his confrontational speech to the reconciliation convention in Melbourne in 1997; and removing the no-disadvantage in the Work Choices industrial laws in 2005.

Howard was a respected but never hugely popular leader. His government was controversial and polarising on issues such as refugee policy, workplace relations, the handling of Pauline Hanson’s xenophobic views, climate change and foreign wars.

Howard stands by the decision to deploy troops to Iraq – the hardest he made – to disarm it of weapons of mass destruction in 2003, arguing it was based on what he thought was reliable intelligence.

Morrison recently revealed he felt “anxiety” that could be “overwhelming” while prime minister and was prescribed medication. Howard was surprised by this and says he enjoyed being prime minister and never found it isolating or stressful. “There were some very difficult decisions,” he says. “But I never felt totally overwhelmed.”

When Howard was elected as the member for Bennelong, Janette was pregnant with their daughter Melanie. They would later have two sons, Tim and Richard. John and Janette, who married in 1971, would form one of the great prime ministerial marriages.

“I have been hugely grateful for Janette,” Howard reflects. “She was an enormous support and assistance to me during the whole time I was in politics, particularly during the wilderness years. I’m blessed for that part of my life.”

In the 50 years since John Howard was first elected to parliament on May 18, 1974, politics has changed profoundly. He believes many MPs now view politics as a game with fewer causes and convictions, the major parties have become too factionalised, and parliament has become dominated by people who view politics as a profession.