IN May 1982, the minister for administrative services, Kevin Newman, wrote to treasurer John Howard, asking him to identify “the most significant achievements” of his portfolio. Howard carefully considered his response.

He named five major economic achievements of the Fraser government: establishing an inquiry into the financial system (the Campbell report); setting up the Foreign Investment Review Board; cracking down on tax avoidance; affordable housing initiatives; and fighting inflation.

A draft of the letter, however, excised a paragraph arguing Australia’s inflation rate compared “favourably” to other OECD countries. It also noted Australia was “in danger of losing this competitive edge … because of wage demands”. That deleted paragraph was prophetic. A year later, the Fraser government was swept from power. The economy was in recession. High inflation and unemployment — stagflation — marred its economic legacy.

Many of the reforms Howard had wanted to implement to address a sclerotic economy and halt declining living standards would be implemented by the Hawke-Keating government.

“It was clear during the 1980s that Australia needed broad economic reforms to taxation, the labour market, industry protection and the financial system,” Howard recalls. The Fraser government’s reforms in these areas were limited. Howard knew it. He would not shirk the reform challenge, in opposition or government, in subsequent years.

The Howard-Newman letters were discovered in Howard’s personal papers, now located at the University of NSW at the Australian Defence Force Academy in Canberra. They were opened to researchers yesterday. This writer was granted the first access to these archives.

The Howard papers — letters, articles, speeches, media releases, transcripts, subject files, media clippings, policy papers, parliamentary files and political documents — will amount to 500m of shelf space. They chronicle Howard’s parliamentary career from 1974 to 2007. The first tranche includes his papers up to 1996.

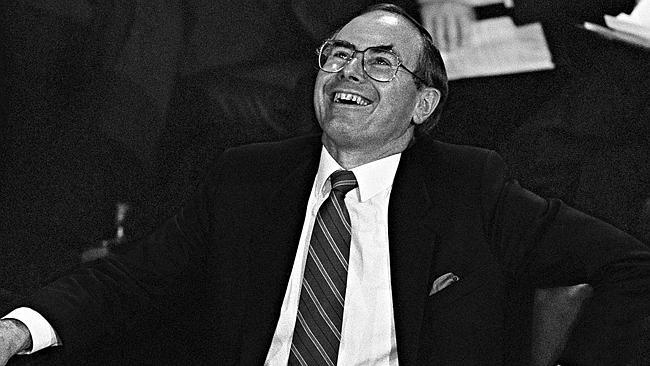

These documents provide fresh insight into Howard’s long years of public service, with plenty of triumphs and moments of despair, as he went from a backbencher elected in 1974 to treasurer (1977-83) and Liberal Party leader (1985-89 and 1995-2007) to prime minister (1996-2007).

In 1975, Howard was appointed minister for business and consumer affairs. One of his key challenges was to oversee reform of the Trade Practices Act, including applying secondary boycott provisions to trade unions. Howard’s files include submissions, policy papers and correspondence on these and other policy issues during this time.

As treasurer, Howard often provided memos to Coalition MPs explaining the Fraser government’s economic policies. One August 1981 note acknowledges the “politically sensitive” issue of housing interest rates and recognised the unpopularity of recent rate increases.

The final years of the Fraser government were rocked by leadership speculation, as Andrew Peacock began a campaign to replace Malcolm Fraser as prime minister. Howard issued a statement in October 1981 saying it was “utterly untrue” he would join with Peacock to challenge Fraser.

The long expected showdown came to a head in April 1982 when Fraser called a partyroom meeting to settle the leadership. Peacock nominated for leader. He was crushed by Fraser, 54 votes to 27. Howard stood for the vacant deputy leader’s position, with Fraser’s backing, and defeated Michael MacKellar by 45 votes to 27 on a second ballot.

Howard’s papers are filed with newspaper clippings reporting the leadership manoeuvring during the Fraser government and through the 1980s. A short statement by Howard expressing his support for Fraser in 1982 went through several drafts.

A sentence responding to speculation about his leadership ambitions — “I am not aware of any moves being made to gain a spill in order to promote me as leader of the party” — was cut from the final version and replaced with a sentence that referred to a spill being encouraged for “whatever purpose”.

In the 1980s and 90s, while Howard served as a shadow minister, party leader and deputy leader, he kept detailed files on the Hawke-Keating government’s policies, statements and scandals. He also kept files that record the opposition’s policy development during this period. Howard’s media clippings from the 70s to the 2000s are extensive.

By the time Howard returned as Liberal leader in 1995, he faced Paul Keating as prime minister. The Howard papers include several files dedicated to Keating’s early political career, his policies and personal interests such as his investment in a piggery. Several files track ministerial and parliamentary scandals during this time.

Among the 10,000 items now transferred are correspondence, speeches and newspaper articles with Howard’s annotations on them. Howard sketched out a July 1995 article on industrial relations, making a note that “new workplace (re-engineering etc) will flourish with workplace choice”.

Businessman Kerry Stokes opened the John Howard Reading Room at UNSW Canberra yesterday. The reading room is near the storage facility that now preserves Howard’s papers, which have been transferred from the National Archives of Australia. The collection is valued at $1 million.

“I hope that they will be a valuable and accessible resource for scholars and students and for anyone with a genuine interest in the political and public affairs of Australia,” Howard told The Weekend Australian.

“Having access to primary sources helps to provide a special insight into the issues and personalities of the period that I was in the federal parliament.”

These papers indeed provide a window into Howard and Australian politics across several decades. The first tranche, amounting to 70m in shelf space, harks back to a time politicians, perhaps, were more dedicated to serving their constituents and were more cognisant of their concerns.

In March 1982, a year before the Fraser government lost office, Howard received a handwritten letter from one of his constituents in his Sydney seat of Bennelong.

The married mother of three children expressed her alarm at payments to unmarried mothers. She was concerned about “bludgers” living off welfare. She believed in reward for effort. She was concerned about crime, discipline for young people and hardworking families struggling to pay bills. “What are you and your government going to do about it?” she asked.

“It is very valuable for politicians and ministers to know that members of the community appreciate that the task of government is not always easy,“ Howard, then treasurer, responded. “I am a family man and I sympathise with much of what you have said about the changing standards in the community. One can only hope that the pendulum will eventually begin to swing in the opposite direction. Indeed, history shows that periods of ‘permissive’ standards in society have usually been followed by a return to more conservative patterns.

“I agree that there is a great need to contain the costs of our social service benefits. But I believe that the problem which concerns you will be solved in the long run only by a change in accepted social standards, and governments in a democratic society cannot bring about such changes by legislation.”

It was the response of a shrewd but understanding politician keenly aware of the values of middle Australia. This woman may have been the original “Howard battler” who helped sustain him in power as prime minister for 11 years and four election victories.