‘It was an attack on all of us’: Howard

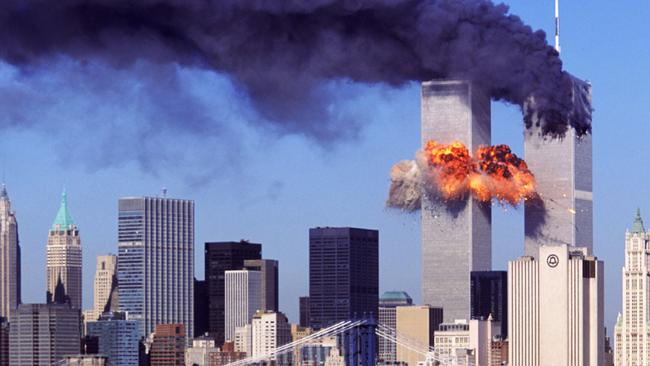

When the first plane smashed into the north tower of the World Trade Centre in New York on the morning of September 11, 2001, John Howard thought it was an accident.

“It had quite an impact on me – just shock, disbelief and, I suppose, an immediate attempt to try and assimilate in my own mind what it all meant for the future,” the former prime minister says in an interview with Inquirer.

“This was an audacious and devastatingly effective attack, which came both literally and metaphorically out of the clear blue sky. This was a more outrageous attack on America than Pearl Harbor because it struck at the security and commercial heart of the country, whereas Pearl Harbor was an attack on a military installation. We would now have to face the prospect of unexpected terrorist attacks on ordinary civilian targets.”

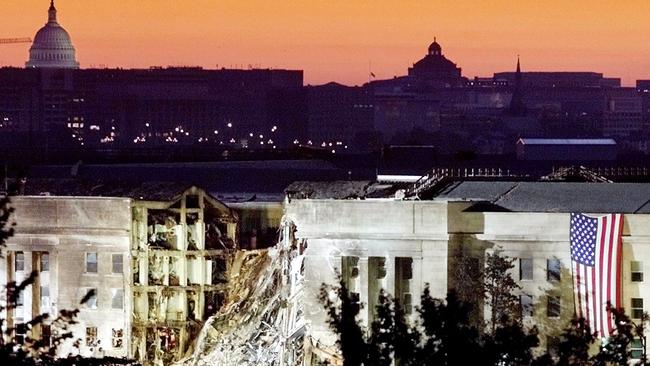

Howard was in a media conference when a third hijacked passenger plane was used as a weapon by al-Qa’ida terrorists to crash into the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia, near Washington. He told reporters the New York attacks were “horrific” and “awful” with “a very big loss of life”. The scale of the carnage was not yet known.

After the press conference, he pulled back the curtains and saw plumes of smoke above the Pentagon. Howard reveals to Inquirer he later was told his original schedule had him visiting the Pentagon on the morning of September 11, possibly around the time of the attack.

The Secret Service evacuated Howard from the hotel. He was escorted to a bunker beneath the Australian embassy. His wife, Janette, and son, Tim, were sightseeing. They were taken to a safe house, a fire station, and then to the embassy bunker.

“It was clearly designed to inflict the maximum amount of terror on Western civilian populations,” Howard says. “It was an attack on all of us in the sense that if it could happen to New York and Washington, it could happen to Sydney or Melbourne.”

Indeed, Howard was alert to the possibility of simultaneous attacks in Australia. He was immediately in contact with deputy prime minister John Anderson. He already had taken steps to increase protection for joint defence facilities, the US embassy and consulates.

“One of the many things that I thought, and discussed with people around me, was the possibility that it was the beginning of a series of attacks,” Howard recalls. “That was a very strongly entertained fear at the time – that there would now be an attack on London, Tokyo, Paris or Sydney.”

The visit to the US was to mark the 50th anniversary of the ANZUS Treaty. Howard had spoken to George W. Bush on the phone when Bush was the Republican candidate for president and after the US Supreme Court determined his election victory, but they had not met in person. On the morning of September 10, Howard and Bush met at the naval dockyard in Washington, where the bell of the USS Canberra was given to the prime minister.

At the White House, they had a formal meeting and a lunch, also attended by secretary of state Colin Powell and national security adviser Condoleezza Rice. That afternoon Howard visited the Pentagon and met secretary of defence Donald Rumsfeld.

Being in Washington when terror struck at the heart of America deepened the personal relationship between Howard and Bush.

“We got off to a friendly start,” Howard says. “I think it was deepened by being in Washington on September 11. I had spent a lot of time with him the day before.”

The consequence of the terrorist attacks was that the US would launch an invasion of Afghanistan a month later. Fear of further attacks would lead to the invasion of Iraq in March 2003. Howard made it clear on September 12 that Australia would “support actions” the US took “to retaliate” in response to the terrorism.

It is “highly likely” Australia would have committed forces to Afghanistan and Iraq if Howard was not in Washington on September 11, he acknowledges.

Pressed on the notion that he vested personal authority, conviction and determination into the twin wars because he had been in Washington, Howard says: “It intensified the strength of my response.” The impact of the September 11 attacks around the world was seismic. It was shocking, horrific, unprecedented. The goodwill, support, empathy with the US was overwhelming. It was one of the most traumatic events in living history.

It was 11.03pm on Australia’s east coast when the second plane crashed into the south tower. Australian TV stations cut into scheduled programming to report the grim news. Nine’s broadcast of The West Wing was interrupted by newsman Jim Waley.

Most Australians, however, were asleep and would not learn of the news that shook the world until many hours later.

Those watching TV saw the towers on fire, people trapped, some leaping to their death, and the city blanketed in dust and debris when they fell.

A fourth hijacked plane crashed in a field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, after the hijackers were overpowered.

All up, the attacks killed 2977 people, including the planes’ passengers and crew. The world had changed forever. “We had not had to deal with terrorist attacks of this audacity before,” Howard says. It would lead to a revolution within government as counter-terrorism became a core priority for state and federal governments.

The US was completely unprepared for a terrorist attack of this type. During the Howard-Bush meeting in the Oval Office, on September 10, the topic of terrorism was not on the agenda and it was not discussed.

“It was a completely new experience,” Howard says. “It was a shocking, shattering event and I don’t think anybody was prepared for it. How can you be prepared for something that you had no warning of? Absolutely no warning? In my discussions with Bush, there was no suggestion that this was going to happen.”

But the Bush administration repeatedly was warned by intelligence agencies that Osama bin Laden was planning to launch a terrorist attack on the US. The CIA’s daily brief handed to Bush just five weeks earlier was titled Bin Laden Determined to Strike in the US.

“They are the sorts of things that are always enhanced by subsequent cataclysmic events,” Howard argues. “If the attack had not occurred, I’m not sure that those warnings would have seen the light of day.”

Fear of another terrorist attack led to sending forces to capture or kill bin Laden and degrade al-Qa’ida and the Taliban in Afghanistan. Following a drawdown of troops in 2002-03, new forces later were sent to fight a resurgent Taliban and the mission changed to also become one of nation-building. Howard does not accept that it was a lost war.

“The principal objective was achieved and the fact that we have not had any more terrorist attacks of that character is pretty significant,” Howard rationalises. “When we put people back in, 2005, the background of that was the possible resurgence of the Taliban and even some indications that al-Qa’ida might be recruiting again.”

Australia joined the invasion of Iraq on the basis that Saddam Hussein’s regime possessed weapons of mass destruction and he had to be disarmed. No such weapons were found. The war distracted the US from Afghanistan. The invasion, without UN sanction, divided the West. That war was lost and Iraq became a haven for extremist terror groups.

“We had a good reason to believe that (WMD) did exist,” Howard says. “There was a distillation of all the intelligence agencies’ assessments and its overwhelming conclusion was the very strong probability that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction.”

Howard acknowledges mistakes were made in disbanding the Iraqi army, dismantling domestic policing capacity and banning Ba’ath party members from holding political office following the invasion. These decisions, implemented on the ground, reversed earlier directives by Bush.

“There were some crucial decisions taken after the invasion that were wrong,” Howard accepts. “The chaos that ensued, partly as a result of that, or rather the inability of the locals to handle the chaos effectively, coloured reactions probably as much as the failure to find stockpiles of weapons.”

While the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan now have ended, and will be debated endlessly, the terror risk has not. Howard says Australia, like the US, is much better prepared to deal with future attacks. But we must remain, as ever, alert but not alarmed about the insidious threat of terrorism.

“It is less likely that we will have another attack like September 11, but the world is unpredictable,” Howard says.

“There are always evil doers who want to attack our way of life. We need primary intelligence, we need an effective national security apparatus and we need to reinforce our relationships with like-minded countries, not just the US and UK but in our own region.”

When the first plane smashed into the north tower of the World Trade Centre in New York on the morning of September 11, 2001, John Howard thought it was an accident. When a second plane hit the south tower, he knew it was an attack. He turned on the television in his Washington DC hotel room and saw smoke billowing from the burning towers.