Friendly fire: John Howard’s stinging critique of the Morrison government

From Scott Morrison’s ‘egregious’ attack on Christine Holgate to expelling Malcolm Turnbull, Peter Dutton and the former government’s failures, the ex-PM doesn’t hold back.

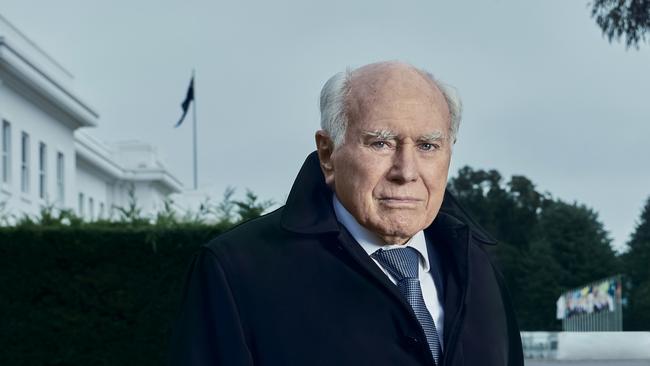

John Howard sits in a comfortable Chesterfield- style wingback chair in the corner of his office high above the Sydney CBD. Over his right shoulder is an expansive view of skyscrapers piercing the blue winter sky to Sydney Harbour and the ocean beyond. His office is bookended with tomes on law, politics and history. An Australian flag stands in the corner. A portrait of Winston Churchill hangs on the wall. A photograph of Robert Menzies sits alongside family portraits and one of the Queen with his ministers. His desk has a computer between piles of papers.

Howard arrived moments earlier, bouncing into the office carrying a briefcase and sharing his enthusiasm that he would later be at the St George Leagues Club for the “Dragons Team of the Century” announcement. A cup of tea is arranged and we sit down for what will be my 19th interview with the former PM over the past decade. The energetic 83-year-old has written his third book, A Sense of Balance, composed mostly during Covid lockdowns, which offers ruminations on policy and political issues at home and abroad, drawn from experience, observation and research.

It is almost 15 years since he exited parliament, losing his seat of Bennelong, and government. Today he is revered by Liberals and respected by Labor contemporaries. He was pressed into service during the recent election, campaigning across the continent, serving the party which served him. Out of politics, Malcolm Fraser sought international appointments, frustrated with how Australians regarded their former leaders, while Bob Hawke and Paul Keating pursued lucrative business interests. Neither model held much appeal for Howard, although he has taken board positions and consultancies such as that with JP Morgan.

Howard speaks when he has something to say, to reflect on anniversaries and defend his record. He does not, like some in the ex-PMs club, interminably attack the other side of politics or undermine his party. That is not to say he pulls his punches but he believes it befits former prime ministers to have a sense of balance, given the dignity of the office they held. “[Be] there when you should be to demonstrate the collective voice of the nation and the solidarity of the country, making useful contributions, but sparingly, to public debate and certainly barracking for your own side,” Howard says of his approach. “I owe the Liberal Party everything that I achieved in politics... I feel very strongly that there is an obligation of reciprocal loyalty… I have got an obligation to contribute in a thoughtful, non-acrimonious way.”

During the recent campaign, whether on street walks or in shopping centres, he was almost always met with a positive response. He shook hands and posed for photos. Memories fade. The Howard government could be chronicled by the protests against it: over guns, reconciliation, refugees, Hansonite racism, workplace relations, climate change and the Iraq war. Attitudes have mellowed, he acknowledges. Howard led the Coalition to four election victories, pinching seats that were once safe for Labor, yet he never reached the popular heights of Hawke. “They haven’t got more hostile, let me put it that way,” he says, tongue-in-cheek, of his fellow Australians. “Maybe, the benign attitude to me is partly because I don’t say too much and I don’t spend a lot of time just banging on about the other side. And it was a stable period, and people do remember it as a good government and we had a good team.”

A Sense of Balancefollows Howard’s best-sellingautobiography Lazarus Rising (2010), and The Menzies Era (2014). The central theme of the new book is that objectivity and perspective in being able to find “a sensible compromise” or “a middle way” should continue to guide policymaking. The Howard government is remembered by admirers as a time of growing prosperity with rising living standards, 10 budget surpluses, retiring $96bn in government debt, the introduction of the GST, gun law reform, peacekeeping in East Timor, generous tax reductions and family payments, encouraging home ownership and more choice in the provision of health and education services. Howard became consoler-in-chief in response to tragedies and disasters such as the Bali bombings. Yet critics will question his call for balance in politics given his government’s confrontation with unions on the waterfront and WorkChoices laws, limiting Native Title, joining the invasion of Iraq, and divisions and scandals over asylum-seeker policies. Not surprisingly, Howard takes the longer view.

“We did have this sense of balance,” he says. “We didn’t perpetuate the arguments in health and education between public and private – we adopted both. We took the best bits of our British inheritance such as the rule of law, parliamentary democracy and a free press. But we didn’t take the bad bits – the class distinction or a tendency to an aristocracy.”

Still, he is concerned about the health of our public discourse, the risk of entrenched tribalism and polarisation, and the loss of a sense of sodality and comity, which could make progress harder. “We have become, like the rest of the world, less rhetorically tolerant,” he says. “We just go overboard. That does worry me, yes. It would be a terrible shame if we lost that. It is still a basic capacity in this country to accept the outcome of [election] results.” After Anthony Albanese was sworn in as Australia’s 31st prime minister, he received a letter from the 25th. Howard became prime minister when Albanese became a Member of Parliament, in 1996. So, what did Howard write in this note of grace to his once fierce critic? “I just said: ‘Congratulations and I hope for the sake of the country that you do well’,” Howard reveals. “And isn’t it good that we live in a society where you can have a seamless transfer of power – it is something that we ought to be pleased about.”

With the election decided, now is the time to learn the lessons of defeat. Howard is critical of the Morrison government in his new book. There are no scores to settle; it comes not from wellsprings of bitterness but a desire to help his party rebuild. “The absence of a program for the future… the absence of some kind of manifesto, hurt us very badly,” Howard says in his first interview since the election. “There’s a shelf-life to arguing that we can manage things better… you have got to keep arguing for something.”

Few will mourn the defeat of the Abbott-Turnbull-Morrison government, just as few grieved the Rudd-Gillard government. Both are remembered, overwhelmingly, for the internecine warfare between the leaders, their Shakespearean falls from power and the revolving-door prime ministership that made Australia the coup capital of the world. The previous Labor and Coalition governments were not devoid of achievements, indeed some were substantial, but overall they were disappointing periods and much more could have been achieved. They cannot be favourably compared to the Hawke-Keating government or the Howard government. Tony Abbott, for one, agrees. “The next generation has to accept that the Howard government did better than us, and to work out why it succeeded better than we did, so that our public life might be better from now on,” he argued recently.

Howard assesses the Morrison government as having “a very mixed” record. He praises its pandemic management, economic performance and national security policies, but writes, in a sentence that will sting former ministers, that the “Coalition baulked at any major economic reform” in the past five years. He also argues that political management was often defective. The failure to put the integrity commission legislation to a vote in parliament allowed critics to say it was not serious about dealing with corruption; not resolving internal differences over its Religious Discrimination Bill meant the government went to the election “in some disarray” on the issue; and he labels Scott Morrison’s attack on Australia Post CEO Christine Holgate “egregious” because she “had not done anything wrong”.

When Malcolm Turnbull challenged Abbott, and succeeded in removing the first-term prime minister, the government struggled to recover. Howard says the former government “suffered very badly” from the leadership changes, which wrought instability and lingering bitterness. “The thing about removing Abbott was that he had done the really difficult thing – he had got the party back into power,” he says. “Only four Liberal leaders have ever done that… he had a marvellous majority… there was no policy reason for Abbott’s removal.”

Howard urged Turnbull to appoint Abbott defence minister after the 2016 election. He made the case at length, but Turnbull was not moved. Howard is reluctant to judge Turnbull’s behaviour after losing the prime ministership, including his failure to endorse his successor in Wentworth, Dave Sharma. “I am disappointed,” Howard says. “It would have been helpful, very helpful. Would it have made a difference? I don’t know. I took the view that as a former Liberal leader I should endorse any Liberal candidate that I was asked to endorse… I know some people [are] running around saying we should expel him [Turnbull]. I’m not in favour of doing that.”

Peter Dutton has talked with Howard several times since becoming Liberal leader. “Peter and I have always got on well,” Howard says. “I was very grateful that he won a seat in 2001 and I made him a minister early in the piece. I was impressed with him. He was a common-sense Queensland copper.”

In A Sense of Balance, Howard shares his concerns about the “pathologies” of the major parties and the fracturing of the two-party system, a mainstay of Australian parliamentary democracy post-war and a source of its stability. At the last election, Liberals lost safe seats to Labor, Greens and Teal independents; Labor lost a seat to the Greens and another to an independent. “Both [major] parties have to work to preserve the two-party system by making their own parties as attractive as possible to its natural constituency,” Howard says. “One of the mistakes the Liberal Party has made is to take its natural constituency for granted... The two parties that did best were the National Party and the Greens – the National Party did brilliantly, they didn’t lose a seat, and the Greens did well, they won seats.

“You had an election where the two competing [major] parties – one of them was unwilling to offer anything because they didn’t want to scare the electorate and had a small-target strategy, and the other felt that it could just get by on arguing that it could manage things better... One of the reasons we suffered more is the Teals did offer, as it happened, something that was attractive to people who were unenthusiastic about the Liberal Party but really couldn’t bring themselves to vote Labor.”

While Howard downplays the notion that Liberals face an “existential” crisis, he is concerned about the party’s loss of members, which has made it less representative of the community than it was, the rise of the professional staffer whose only experience is in the “mechanics of politics” and the divisiveness of factions. “Factionalism has poisoned the Liberal Party’s body politic,” Howard writes. It has had a “destructive” impact in multiple states but preselection delays, due to factional game-playing, were especially damaging in NSW. He ticks off NSW Treasurer Matt Kean for making a “rogue intervention” to say the party’s candidate for Warringah, Katherine Deves, should have been disendorsed.

The Liberal Party, Howard argues, must remain a home for liberalism and conservatism with commitments to free enterprise, individualism, supporting families, keeping taxes and spending low, and supporting alliances with the US and UK. He pours scorn on those who say the party must be either wholly liberal or wholly conservative. “Beware of false choices,” Howard says. “We do best when we do have a broad church. We can accommodate both streams.”

Looking at the UK and the US, Howard is troubled by what he sees. While a supporter of Brexit, given issues of identity, migration and onerous EU regulations, he is critical of Boris Johnson’s probity failures and is not surprised by the cabinet revolt that forced him to resign. Howard says Johnson’s Downing Street parties showed he was “out of touch” with voters. Even more concerning is Donald Trump, who has admirers and defenders among reactionary conservatives in Australia. Howard says Trump is “unfit” to return to the presidency. “I am not any fan of Trump,” he says. “His behaviour since losing the election has been disgraceful and I just hope, pray, that the Republicans will find somebody else to get behind because he has behaved terribly.”

Howard writes broadly on foreign policy in the book. He recalls the 9/11 terrorist attacks and defends his government’s decisions to send forces to Afghanistan and Iraq, noting the latter was the “most difficult” of his prime ministership. He is critical of the hasty US withdrawal from Afghanistan. He insists that Australia will not have to choose between its security relationship with the US and its economic relationship with China. He believes it is “highly unlikely” China will launch a conventional attack on Taiwan or that China will surpass the US as the world’s superpower. He suggests “self-respecting pragmatism” should guide Australia’s relationship with China, given that the trade partnership is vital.

An ardent royalist, Howard praises the Queen and the virtues of constitutional monarchy, rebuking those who argue the Governor-General is actually Australia’s head of state. And he mocks those who claim vice-regal correspondence between Sir John Kerr and Buckingham Palace proves the Queen authorised the Whitlam government’s dismissal, saying there is no such evidence.

When Howard was elected to parliament in 1974, Gough Whitlam was at the midpoint of his reforming and turbulent government. Howard says he always enjoyed Whitlam’s company. In 1996, he said he had “a warm personal regard” for Whitlam and admired his success in leading Labor to power after 23 years in opposition.

Howard is generous towards Fraser, who became Liberal leader and prime minister in 1975 and appointed him minister for business and consumer affairs after the election that year. Howard rose rapidly and became treasurer in 1977. He clashed with Fraser on economic policy. “[Fraser] made his name and imprinted his influence on the party as an advocate of open markets,” Howard recalls. “He would eulogise Milton Friedman and Ayn Rand but when he actually got there, he was an [economic] interventionist.” Most in the cabinet and party room were in those days.

Andrew Peacock led the Liberal Party in opposition after the 1983 election. Howard remained deputy leader, having secured that position the year earlier. The pair collided along multiple fault lines: Melbourne v Sydney; liberal v conservative; style v substance. “There were faults on both sides with Peacock and me,” Howard concedes. “I guess it was one of those preordained clashes.” In 1985, in a truly bizarre moment, Peacock accused Howard of disloyalty and asked the party to replace him as deputy leader. When Howard survived as deputy, Peacock promptly resigned. Howard then stood for leader and won.

It was a treacherous time for the Coalition. Howard and National Party leader Ian Sinclair were undermined by Queensland premier Joh Bjelke- Petersen’s quixotic attempt to switch to federal politics and become prime minister. The Coalition split. Hawke led Labor to a third election victory in a row in 1987. “It was just an unbelievably difficult period that, and [Joh] completely fractured the Coalition,” Howard recalls. “Would we have won in ’87 without Joh for PM? I don’t know, but the polls at the beginning of the year were pretty good.”

The Liberals supported Labor’s financial deregulation, tariff reductions, privatisation, fiscal consolidation and the introduction of the Higher Education Contribution Scheme. It sticks in Howard’s craw that Labor did not “return the compliment” when he was in office; “bipartisanship was a one-way street”.

Hawke and Keating argued that they did not need Coalition support because they had the support of voters. The Australian Democrats often voted with Labor in the Senate. Moreover, the Coalition did not support the Prices and Incomes Accord, the introduction of fringe benefits or capital gains taxes, or universal superannuation.

Howard became a victim of a leadership coup in 1989. Peacock returned to the leadership. After the 1990 election defeat, the party overlooked Howard and chose John Hewson as leader. In 1994, the party overlooked Howard again and selected Alexander Downer as leader. With only a slim chance he could return to the leadership, Howard focused on industrial relations policy and looked to return to the ministry in a future Coalition government. But when Downer became gaffe-prone, the party did look to Howard and he returned to the leadership unopposed in 1995. He led the Coalition to a landslide election victory a year later.

It was an extraordinary comeback. Howard would go on to win three more elections – equalling Hawke – and become the second-longest serving prime minister. He recognises the stability and continuity in the three most senior positions of government, with Peter Costello as treasurer and Downer as foreign minister, over 11-plus years.

Looking back, Howard names economic and budget management as important achievements and rates gun law reform following the 1996 Port Arthur massacre as an especially proud moment. “We left the country stronger, prouder and more prosperous than what we inherited,” he says. “I am very proud of the gun measure. What cheers me about that is it was just one of those things that unarguably made people feel safer.”

Pressed to identify things he might have done differently, Howard names the decision to take the “no-disadvantage test” out of the Workplace Relations Act. “That was a mistake,” he admits. “You only get one go at getting something like that right.” While Howard regrets his speech to the 1997 Australian Reconciliation Convention, where he lost his temper as some in the audience turned their backs on him, he does not regret not attending Kevin Rudd’s apology to the Stolen Generations in 2008. “That would have been hypocritical,” he says. “I had expressly eschewed delivering an apology.” He argues that while our treatment of Aboriginal Australians in the past constituted “a grievous national failure”, he still believes that one generation cannot apologise for past misdeeds. “Only real-time apologies have credibility.”

In 1999, Howard put a referendum that would honour Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians as “the nation’s first people” in a preamble to the Australian Constitution. It failed, along with the republic model endorsed by the Constitutional Convention. Howard says he will make up his mind on a Voice to Parliament when the proposal is clear.

In canvassing a range of legal, ceremonial and constitutional issues, he offers some surprising reflections in his new book. He supports amending the Constitution to allow the House and Senate to meet in a joint sitting to resolve deadlocks without a double dissolution. He does not support compulsory voting. And he voted for Waltzing Matilda to be the national anthem in the 1977 plebiscite.

As for climate change, it is worth remembering that Howard pledged to introduce an emissions trading scheme if re-elected in 2007. Today he is “agnostic” on climate change, wary of “alarmist predictions”, and supports removing the ban on developing a nuclear power industry.

Having served almost two decades as leader or deputy leader of the Liberal Party, Howard knows a thing or two about leadership. Australia has had seven prime ministers (counting Rudd twice) in less than 15 years. This churn has been hugely disruptive to the Australian polity. “The fundamental relationship is that between the leader and the immediately led,” Howard says. “If you don’t have a good relationship with your parliamentary colleagues, you have got a problem.” He adds: “Even with people who were very unhappy with my stance on asylum seekers, I never lost contact with or found myself unable to communicate with that group.”

Howard identifies Menzies as Australia’s greatest prime minister. He adds that Hawke was the best Labor PM, and rates NSW Premier Neville Wran as a most impressive Labor leader. He has, over the years, gained more respect for John Gorton. And the person who would have made a successful prime minister? He nominates Kim Beazley.

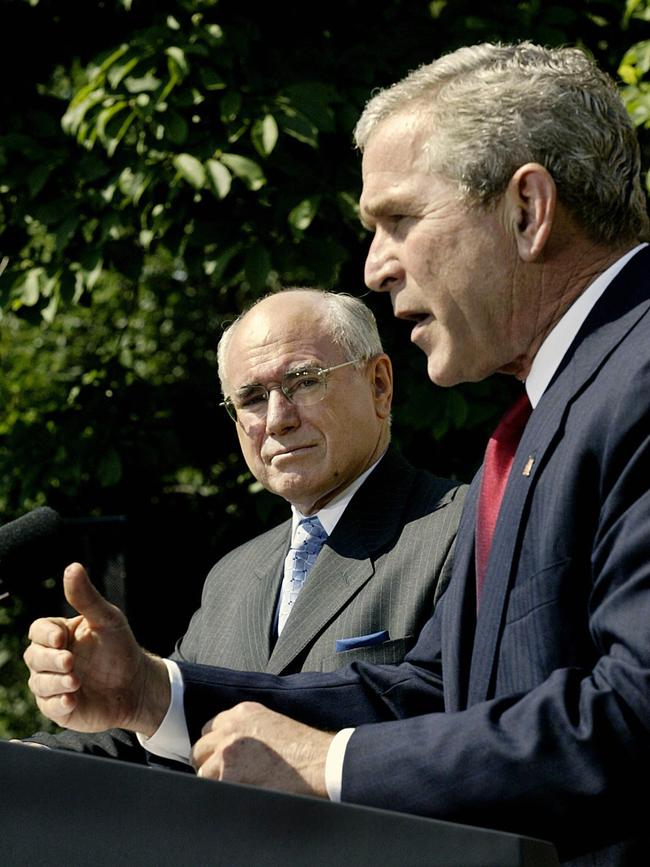

During his three-plus decades in parliament, Howard met with many world leaders. He has great admiration for Margaret Thatcher, and a high regard for Benjamin Netanyahu. He enjoyed working with Tony Blair, and says he got on very well with George W. Bush and Bill Clinton.

During the 1996 election campaign, reporter Liz Jackson asked Howard about his vision for the year 2000. He wanted Australians to feel “comfortable and relaxed” about the present and the future, he responded. Although pilloried at the time, it may not sound too bad now given the risk of further division and tribalism in public life. “We have got to be a conscientious country, but we also should preserve our capacity not to take ourselves too seriously,” he says. “I don’t want to see politics polarised in this country, I don’t. And it’s got to be possible to be gracious across the divide every so often.”

Howard has adjusted to post-prime-ministerial life; he remains mentally and physically active, walks most mornings and plays golf regularly, and reads widely. He feels “blessed” to have the companionship and support of his wife of 51 years, Janette, and highly values his relationship with their three children and grandchildren. But he admits he misses the privilege of holding the highest office in Australia. “To say you don’t miss it is wrong, of course you do,” Howard says. “I am always suspicious of people who say, ‘I’m glad I’ve no longer got this extraordinary privilege and power.’ I mean, really? Now, I was lucky; I had a lot of luck. But I had some unexpected and undeserved hurdles along the way. So, you’ve got to have a sense of balance about that as well.”

John Howard’s A Sense of Balance (HarperCollins, $39.99) is out on August 17.

-

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout