Cabinet Papers 2002: Kyoto rejection the moment the climate wars gained steam

Concerns the Kyoto protocol would ‘risk Australia’s competitive advantage in emissions-intensive activities’ were one reason behind Howard government’s refusal to ratify the agreement.

A major campaign to “counter negative perceptions” of Australia’s stance on climate change and refusal to ratify the Kyoto Protocol was recommended ahead of a significant international summit on sustainability in 2002.

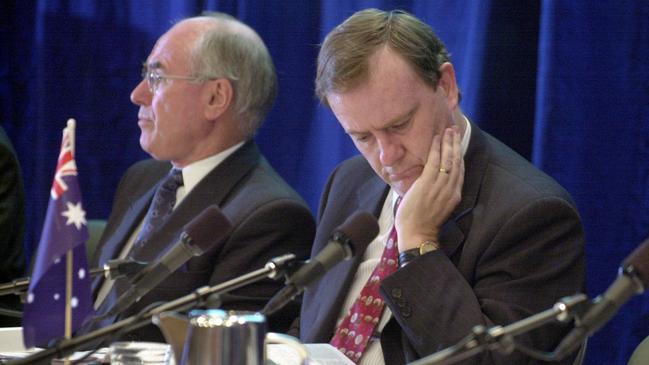

Cabinet documents from the time released by the National Archives showed the Howard government raise concern with pressure it was likely to receive at the World Summit on Sustainable Development, with senior ministers recommending Australia work strategically with the US to “shore up support” for its opposition to Kyoto and new financing for developing countries.

The Howard government agreed it would lobby instead for only voluntary initiatives to be pursued at the summit and for “unrealistic targets and timetables” to be avoided.

CABINET PAPERS 2002

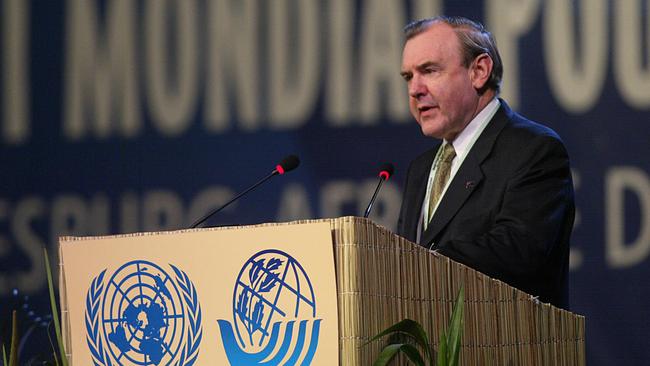

‘Advantage lost’: Costello slams inaction on debt

Twenty years after warning cabinet of significant future budget pressures, former Treasurer Peter Costello says the fiscal and debt position of the nation is far worse than it needed to be.

‘I don’t have time for egomaniacs who take notes’

Amanda Vanstone lifts the lid on her time in cabinet, including her dealings with John Howard and disdain for ministers more concerned with publishing memoirs than serving the community.

Why Howard government refused to say sorry

Fears that present day Australians would be held responsible for atrocities of the past were behind the Howard government’s refusal to apologise to Indigenous Australians in 2002.

Hicks’ Guantanamo detention ‘lawful’, government ruled

Australian and US governments agreed on the need for a ‘consistent public position’ on Guantanamo detainee David Hicks, cabinet minutes from February 2002 reveal.

‘Why we never ratified Kyoto was beyond me’: Costello

Peter Costello laments rejection of 1997 Kyoto Protocol as cabinet documents from 2002 reveal Treasury argued for incentives to invest in cleaner energy.

Howard warns on ‘reform fatigue’

John Howard and Peter Costello urge major parties to prioritise deficit and debt reduction to protect the nation from the next major economic shock.

How Kyoto rejection kickstarted the climate wars

Concerns the Kyoto protocol would ‘risk Australia’s competitive advantage in emissions-intensive activities’ were one reason behind Howard government’s refusal to ratify the agreement.

Frustration over new security laws post-9/11

The Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet feared its inability to get state agreement on contentious new security measures in the wake of September 11.

How 9/11, Bali bombings changed our military

With the threat of terrorism looming large, the Howard government created a national special forces command to ensure ‘surgical’ military responses.

Release of Bali bombmaker ‘regrettable’

Former PM sympathises with victims and relatives over early release from jail of Bali bombmaker Umar Patek.

Australia wary of Afghanistan troop commitment

Declassified national security committee documents reveal that in June of 2002, Defence argued it was ‘not in a position to contribute’ to UN force in Afghanistan.

Christmas Island detention centre’s fast-tracking revealed

The Howard government fast-tracked plans to build the first ‘purpose-designed and built’ offshore detention centre controlled by Australia in 2002.

Timor Sea Treaty negotiations to be kept under wraps

Disclosure of details on joint resource-sharing agreement between East Timor and Australia would “damage security”, National Archives rules.

Push to restrain growth of disability pension

Concerns over ‘inappropriate access’ to the Disability Support Pension prompted Howard government to introduce measures to reduce number of recipients, cabinet papers from 2002 reveal.

“We should work to shift perceptions away from participation in Kyoto being the test of a country’s commitment to a climate change response,” environment minister David Kemp and foreign affairs minister Alexander Downer told cabinet in a report in July 2002.

“Norway has taken the lead with support of the EU and developing countries in pushing for a text that urges all countries to ratify the Kyoto protocol. Australia, with the US and Russia, has opposed such language and we should continue to do so.”

The cabinet documents from 2002 showed the Howard government saw the Kyoto protocol as able to make “only a modest contribution” in reducing greenhouse emissions, particularly because it lacked the support of the US.

In designing a strategy to tackle emissions, the Coalition wanted to be careful to not risk the “competitive advantage in economic activities that are currently greenhouse gas emissions intensive”.

It was here where the climate wars that would dominate the next two decades of Australian politics gained steam, with the Albanese government’s 2030 target to reduce emissions by 43 per cent on 2005 levels still vigorously opposed by the Coalition.

Ahead of the summit, Mr Kemp and Mr Downer also told cabinet Australia should “oppose initiatives that would have parties commit themselves to an increase in the proportions of renewables in total energy supply”.

“We would be concerned that such initiatives may lead to an international regime on renewables,” they said in a submission.

While trying to manage perceptions of its climate change commitments abroad, the government turned its focus at home to “reversing the long term decline of native vegetation” and extending the country’s Natural Heritage Trust.

Cabinet agreed in 2002 to extend the Natural Heritage Trust by five years to ensure the body continued to fund projects for native bush restoration, biodiversity and water quality.

But efforts to have states commit “new and additional matching funding” came up against major opposition from almost all jurisdictions.

“Ministers from all states except South Australia and the Northern Territory have written indicating their opposition to ‘new and additional’ matching funding for the Trust,” a cabinet document read.

“The first phase of the Trust allowed for in-kind contributions from jurisdictions and they argue that … the Commonwealth is trying to increase unreasonably the funding.”

As a result, Environment Minister David Kemp and Agriculture Fisheries and Forestry Minister Warren Truss recommended a more “flexible” position in negotiating with states, which would allow for “in-kind contributions”.

But the recommendation was met with alarm by the Department of Treasury, which told cabinet that “accepting in-kind contributions gives the states an opportunity to evade their funding obligations through ongoing cost shifting”.

“Should in-kind contributions be seriously considered, they ought to be subject to strict cost equivalence underpinned by transparent and verifiable performance agreements,” treasury officials said in a submission.

The Finance Department urged for “ministerial intervention” if necessary to force the states to come to the negotiating table.

Treasury also raised concern with the idea of “strengthening industry incentives” for sustainable use of natural resources, pointing to such measures as “government intervention that has the potential to waste public funds and introduce economic distortions”.

Later cabinet documents reveal bilateral agreements with most states were expected to be made by September 2002, but with the option of in-kind contributions remaining.

“The Commonwealth… has secured a commitment from the states and territories to provide resources and transparency in contributions,” the documents read.

“Matching funding may include both cash and appropriately costed and audited in kind contributions.”

The decades of ineffectual environment laws and the “double up” between states and territories that followed would become a key plank of the Albanese government’s platform, with its milestone response to the Graeme Samuel review this month committing to a green cop on the beat that would ensure threatened species and declining ecosystems were better protected.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout