Cabinet Papers 2002: Why Howard government refused to say sorry to Indigenous Australians

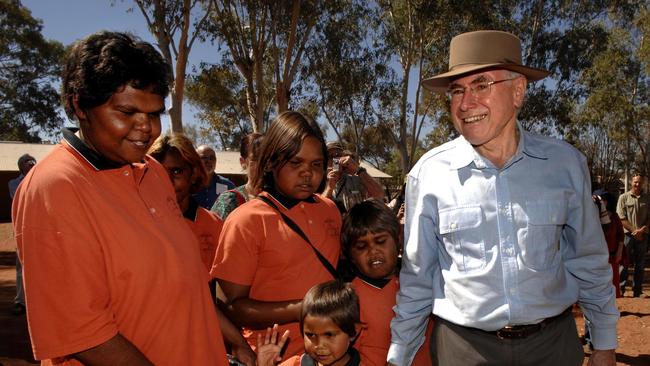

Fears that present day Australians would be held responsible for atrocities of the past were behind the Howard government’s refusal to apologise to Indigenous Australians in 2002.

The Howard Government refused to issue an apology to Indigenous Australians in 2002 despite recommendations in a milestone report, primarily because it would have implied present day generations were responsible for atrocities to generations of the past.

In cabinet minutes from 2002 released by the National Archives on Sunday, the then-Coalition government agreed it would not issue any kind of apology or pursue a treaty between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

However, cabinet did cautiously endorse an “acknowledgment of the special place of Indigenous people in the life and history of Australia” on certain occasions such as citizenship ceremonies, marking the first step towards the acknowledgment and welcome to country that would become commonplace within coming decades.

CABINET PAPERS 2002

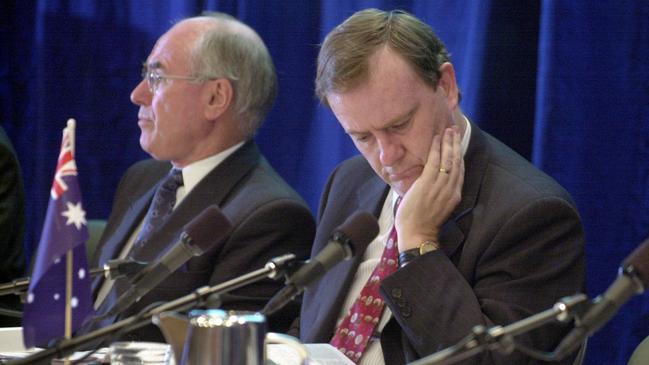

‘Advantage lost’: Costello slams inaction on debt

Twenty years after warning cabinet of significant future budget pressures, former Treasurer Peter Costello says the fiscal and debt position of the nation is far worse than it needed to be.

‘I don’t have time for egomaniacs who take notes’

Amanda Vanstone lifts the lid on her time in cabinet, including her dealings with John Howard and disdain for ministers more concerned with publishing memoirs than serving the community.

Why Howard government refused to say sorry

Fears that present day Australians would be held responsible for atrocities of the past were behind the Howard government’s refusal to apologise to Indigenous Australians in 2002.

Hicks’ Guantanamo detention ‘lawful’, government ruled

Australian and US governments agreed on the need for a ‘consistent public position’ on Guantanamo detainee David Hicks, cabinet minutes from February 2002 reveal.

‘Why we never ratified Kyoto was beyond me’: Costello

Peter Costello laments rejection of 1997 Kyoto Protocol as cabinet documents from 2002 reveal Treasury argued for incentives to invest in cleaner energy.

Howard warns on ‘reform fatigue’

John Howard and Peter Costello urge major parties to prioritise deficit and debt reduction to protect the nation from the next major economic shock.

How Kyoto rejection kickstarted the climate wars

Concerns the Kyoto protocol would ‘risk Australia’s competitive advantage in emissions-intensive activities’ were one reason behind Howard government’s refusal to ratify the agreement.

Frustration over new security laws post-9/11

The Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet feared its inability to get state agreement on contentious new security measures in the wake of September 11.

How 9/11, Bali bombings changed our military

With the threat of terrorism looming large, the Howard government created a national special forces command to ensure ‘surgical’ military responses.

Release of Bali bombmaker ‘regrettable’

Former PM sympathises with victims and relatives over early release from jail of Bali bombmaker Umar Patek.

Australia wary of Afghanistan troop commitment

Declassified national security committee documents reveal that in June of 2002, Defence argued it was ‘not in a position to contribute’ to UN force in Afghanistan.

Christmas Island detention centre’s fast-tracking revealed

The Howard government fast-tracked plans to build the first ‘purpose-designed and built’ offshore detention centre controlled by Australia in 2002.

Timor Sea Treaty negotiations to be kept under wraps

Disclosure of details on joint resource-sharing agreement between East Timor and Australia would “damage security”, National Archives rules.

Push to restrain growth of disability pension

Concerns over ‘inappropriate access’ to the Disability Support Pension prompted Howard government to introduce measures to reduce number of recipients, cabinet papers from 2002 reveal.

It followed the recommendations by then-Minister for Indigenous Australians Philip Ruddock, who advised cabinet to reject a number of recommendations in the milestone report “Reconciliation: Australia’s Challenge”, handed to the government almost 18 months earlier by the Council of Aboriginal Reconciliation.

Mr Ruddock told cabinet that it should reject all recommendations dealing with a treaty and an apology.

“The government’s position on calls for an apology for the past treatment of Indigenous people is that it would be inappropriate to do so as it could imply that present generations are in some way responsible and accountable for the actions of earlier generations,” he said in his submission to cabinet.

“The government’s position on calls for a treaty between Indigenous and other Australians is that to pursue such negotiations would be divisive, contrary to the concept of Australia as a single nation, could create legal uncertainty and that a treaty will not solve the critical issues facing Indigenous Australians.”

Mr Ruddock admitted the rejection of the recommendations would draw criticism, but that this would be nothing new to the Howard government.

“The response is likely to be criticised as not committing to a national apology or negotiation of a treaty, but this criticism will not be new as the government’s position on these issues is already well known,” he said.

An apology to Indigenous Australians would be made by the Rudd government in 2008, despite members of the Coalition – including its current leader, Peter Dutton – voting against such a move.

Since becoming opposition leader following the May election, Mr Dutton conceded he was wrong not to support the apology.

While refusing to support many of the recommendations in the report, Mr Ruddock backed the incorporation of “reconciliation values” in Commonwealth ceremonies.

However, he noted such a move would need to be done gradually.

“The implementation of any such initiative could be gradual as changes to some ceremonies and protocols would require only administrative action, while others may involve changes to regulation,” he said.

“I propose that the implications and feasibility of implementing changes to ceremonies identified be addressed by a limited life interdepartmental committee.”

Cabinet endorsed Mr Ruddock’s submission, which included the rejection of a preamble in the constitution that would recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders as “the first peoples of Australia” and the refusal to enshrine Indigenous rights in a formal bill of rights.

Instead, cabinet noted that “the best guarantee of fundamental human rights is Australia’s vigorous and open political system, an incorruptible judicial system and a free press”.

In separate cabinet documents, the Howard government canvassed efforts to water down a draft declaration on the rights of Indigenous people being proposed by the United Nations, and to strip the phrase “self-determination” from such a document.

Self-determination was controversial at the time because “it has no settled meaning and can imply the establishment of separate nations or separate laws”, with Australia working bilaterally with Canada in particular to seek an alternative to such language in the UN declaration.

The move foreshadowed Australia’s refusal to sign the final declaration, along with Canada, New Zealand and the US, despite more than 140 countries doing so.

It came just months before Kevin Rudd was elected in December 2007, with Australia eventually signing the declaration in 2009.

Cabinet documents also revealed the agreement to Mr Ruddock recommendation for a review into the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission, established by the Hawke government in 1990.

Intended to be a body to give Indigenous people a say in policies affecting their lives, it came under criticism in following years, particularly for promoting the concept of self-determination.

Cabinet agreed a “small team” would investigate the role and “underlying issues” of ATSIC, which had not undergone a comprehensive review in its 12 years of operation.

“ATSIC has evolved from an organisation focusing on delivering Commonwealth programs to Indigenous people and providing Indigenous policy advice to government, to a body more concerned with advocating Indigenous views on a range of issues and promoting a ‘rights’ agenda,” Mr Ruddock said in a submission to cabinet.

The proportion of Indigenous people who voted at ATSIC elections never exceeded a third of eligible voters and had been “falling marginally” since 1993, Mr Ruddock noted.

“If ATSIC were seen as more relevant among Indigenous people in general, increases in the voter participation rate could be reasonably expected,” he said.

Rather than a “full scale public assessment” by a high ranking individual or group that would entail submissions and hearings, Mr Ruddock recommended a “lower profile process” with a small team agreed to by the prime minister that would talk to the ATSIC board and relevant parties before drafting a discussion paper for stakeholders.

ATSIC would be dissolved within three years of the review being triggered, with no replacement body announced until two decades later, when the Albanese government declared it would enshrine a voice to parliament by the end of 2023.

However, the Albanese government has made clear the voice would not be given powers to administer programs or allocate any funding or administer programs, as ATSIC had done, and be a purely consultative body.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout