2002 Cabinet Papers: How September 11 attacks, Bali bombings changed our military

With the threat of terrorism looming large, the Howard government created a national special forces command to ensure ‘surgical’ military responses.

The threat of terrorism loomed large for the Howard government after 9/11 and the October 2002 Bali attacks, prompting the creation of a national special forces command to ensure “surgical” military responses to unconventional attacks.

And two decades before the Albanese government’s search for a long-range strike capability, the Howard cabinet agonised over the continued viability of the nation’s “unique” F-111 fighter-bombers, which had twice the range of today’s F-35s.

Newly-released 2002 cabinet documents also reveal concern over the financial impact of Australia’s participation in the War on Terror, with the cost of troop, aircraft and ship deployments to the Middle East adding $1.8bn to the Defence budget in 2001-02 and $1.96bn in 2002-03.

CABINET PAPERS 2002

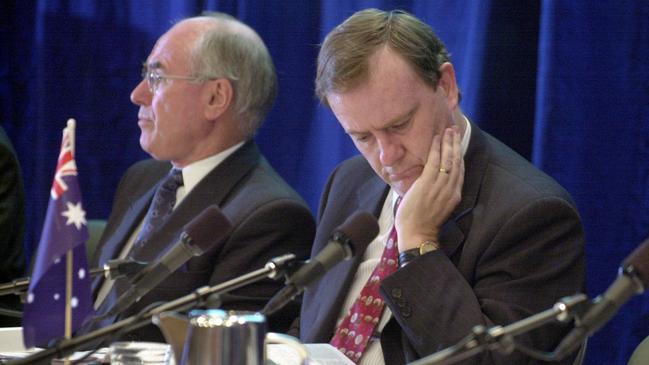

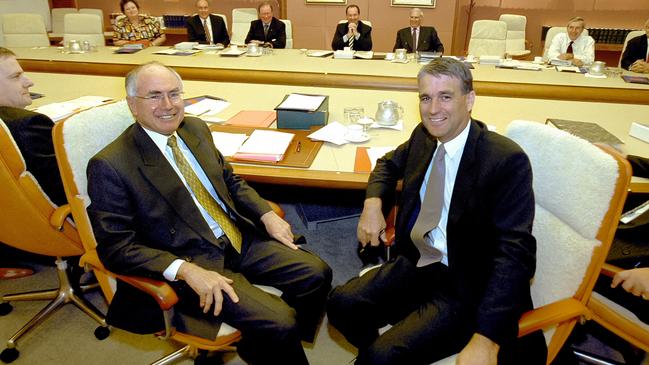

‘Advantage lost’: Costello slams inaction on debt

Twenty years after warning cabinet of significant future budget pressures, former Treasurer Peter Costello says the fiscal and debt position of the nation is far worse than it needed to be.

‘I don’t have time for egomaniacs who take notes’

Amanda Vanstone lifts the lid on her time in cabinet, including her dealings with John Howard and disdain for ministers more concerned with publishing memoirs than serving the community.

Why Howard government refused to say sorry

Fears that present day Australians would be held responsible for atrocities of the past were behind the Howard government’s refusal to apologise to Indigenous Australians in 2002.

Hicks’ Guantanamo detention ‘lawful’, government ruled

Australian and US governments agreed on the need for a ‘consistent public position’ on Guantanamo detainee David Hicks, cabinet minutes from February 2002 reveal.

‘Why we never ratified Kyoto was beyond me’: Costello

Peter Costello laments rejection of 1997 Kyoto Protocol as cabinet documents from 2002 reveal Treasury argued for incentives to invest in cleaner energy.

Howard warns on ‘reform fatigue’

John Howard and Peter Costello urge major parties to prioritise deficit and debt reduction to protect the nation from the next major economic shock.

How Kyoto rejection kickstarted the climate wars

Concerns the Kyoto protocol would ‘risk Australia’s competitive advantage in emissions-intensive activities’ were one reason behind Howard government’s refusal to ratify the agreement.

Frustration over new security laws post-9/11

The Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet feared its inability to get state agreement on contentious new security measures in the wake of September 11.

How 9/11, Bali bombings changed our military

With the threat of terrorism looming large, the Howard government created a national special forces command to ensure ‘surgical’ military responses.

Release of Bali bombmaker ‘regrettable’

Former PM sympathises with victims and relatives over early release from jail of Bali bombmaker Umar Patek.

Australia wary of Afghanistan troop commitment

Declassified national security committee documents reveal that in June of 2002, Defence argued it was ‘not in a position to contribute’ to UN force in Afghanistan.

Christmas Island detention centre’s fast-tracking revealed

The Howard government fast-tracked plans to build the first ‘purpose-designed and built’ offshore detention centre controlled by Australia in 2002.

Timor Sea Treaty negotiations to be kept under wraps

Disclosure of details on joint resource-sharing agreement between East Timor and Australia would “damage security”, National Archives rules.

Push to restrain growth of disability pension

Concerns over ‘inappropriate access’ to the Disability Support Pension prompted Howard government to introduce measures to reduce number of recipients, cabinet papers from 2002 reveal.

The post-September 11 security environment marked a shift from the “Defence of Australia” doctrine that had dominated for decades to an era of expeditionary deployments in Afghanistan and later Iraq. But there was also growing concern that terrorists could strike Australians at home.

In December 2002 – two months after the Bali bombings – the national security committee agreed to establish an ADF Special Operations Command to ensure “increased responsiveness” to terror threats.

“It is evident that Australia and its interests are a potential target of terrorist attacks,” then-defence minister Robert Hill told cabinet’s national security committee.

“There is a high probability that effective measures to thwart terrorist activity against Australia will include the need for ‘militarily surgical’ operations where responses to terrorist attack would need to be well co-ordinated and relatively large-scale in nature.”

Senator Hill said “unity of command” was essential to special forces operations because of the “near zero” warning times and the need to exploit brief windows of opportunity.

The arrangement, which persists today, brought the Special Air Service Regiment, the 4 RAR Commando Regiment (now the 2 Commando Regiment), Tactical Assault Groups East and West (drawn from the Commandos and SASR), the 1 Commando Regiment, and a specialist Incident Response Regiment, under the command of a two star general.

The move added an additional 334 special operations personnel, including logistics and support soldiers and an extra 310 “war fighters”.

“Establishment of the SOC will enable Maritime, Land and Air Commands to focus on their primary tasks of providing conventional military response options while the SOC provides to government non-conventional and special military response options,” Senator Hill told the committee.

Months earlier, the NSC was forced to come to grips with the growing costs of supporting the ageing F-111s, as it considered a fix for cracked wings that forced the aircraft to be grounded.

Senator Hill recommended second-hand wings be purchased from the US, but warned “there is an ongoing risk of further fatigue and supportability problems”.

At the time, Australia had 21 of the aircraft, which had a range of more than 4000km, compared to about 2000km for the fifth generation F-35.

Senator Hill warned keeping the aircraft flying until their scheduled retirement in 2015-20 would cost $2.7bn in operating costs, and there was no guarantee the aircraft would last the distance.

“While the operational impact of the wing failure is expected to be temporary, it is indicative of the type of aircraft structural issues that can emerge unexpectedly,” the minister’s cabinet submission said.

Ultimately, the F-111s were scrapped in 2010, leaving Australia without a long-range strike aircraft to this day.

At the time, the NSC was considering whether to join the US government’s F-35 Joint Strike Fighter development program for an initial cost of $300m.

The submission noted the F-111s “unique capability” as a surface strike weapon could not be replaced with a single aircraft.

The Howard cabinet had hoped the F-35s would be available by 2012. Ultimately, the first of the aircraft was not accepted into Australian service until 2018, and the nation’s first F-35A squadron became operational in 2021.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout