You never know how you’ll react when someone points a gun at your head and orders you into a car. The fear, uncertainty and outright shock play out in different ways.

The men who bundled us into their car seemed to be some kind of Iraqi paramilitary – and they were angry.

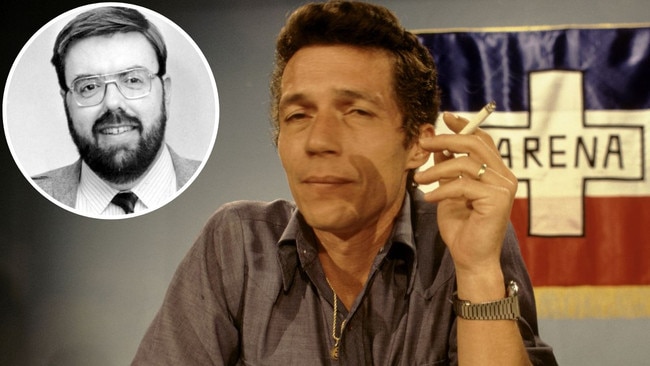

I glanced over at my colleague, Peter Wilson, as we were driven through the deserted streets of Basra in southern Iraq, still occupied by Saddam Hussein’s forces. Peter was sweating profusely and the colour had drained from his face.

My memory of the car ride was a feeling of floating above the entire scene as if it was a movie. I mentally said my goodbyes, fearing the worst.

Our luck had held during our brief time in Iraq – until now. We’d crossed the border from Kuwait several days earlier, tailgating a supply convoy to slip past the erratic and trigger-happy Iraqi border guards.

We were well prepared: chemical warfare suits, a satellite phone the size of a small phone booth, a decent four-wheel drive (after leaving a $30,000 deposit on my corporate credit card) and, most importantly, an excellent interpreter in British-Lebanese “fixer” Stewart Innes. But now we were in Iraq, alone, without any security during a war.

Most of the other journalists in the country were embedded with the US or UK military. Our mission was to focus on ordinary Iraqis, not the soldiers.

Our first encounter with locals was both sad and terrifying: they seemed desperate. These people had put their faith in the West once before, and had been tortured or killed by Saddam’s regime after troops they trusted pulled out and left them for dead.

That night we slept near a British checkpoint. The soldiers made it clear they were unable to protect us, but we felt more secure camped close by. We had a small tent and a car to sleep in. I took the tent, listened as the coalition bombed Basra, and tried to get some sleep using my flak jacket as a pillow.

The next few days were amazing. Work was thrilling and my images were flying through the clear desert sky from the sat phone. Some of my strongest pictures were taken during this period, including some of Iraqi prisoners being marched along a road by coalition soldiers, and families fleeing the fighting in Basra, which was being bombarded by the coalition.

Then we made that fateful decision to venture into Basra. The idea was to speak to some locals, take some pictures and get the hell out of there as quickly as possible. I remember passing the final British checkpoint hoping we had made the right decision.

We were just finishing interviewing a grain silo worker about to flee the city with his family when the car pulled up and we were pushed in at gunpoint. We learned later the locals assumed these men would take us and slit our throats.

We were taken to a room adorned with Saddam Hussain portraits and interrogated about what we were doing in Iraq.

Peter whispered that if they were going to kill us we would be dead by now, which made me feel slightly better. At this stage I thought some light relief might be in order, so I asked if they’d mind if I photographed them – and that I’d kill for a beer. Neither request went down well.

After an hour or so we were taken to the Basra Sheraton where our interrogation continued with a different bunch of equally unsmiling guys. I think that was meant to unsettle us, and it worked.

The bombing continued overnight, and in the morning our captors announced we were to be taken to Baghdad – an all-day journey through fierce fighting. We’d always planned to end up in Baghdad, but the idea had been to follow the war – not drive through it.

At one stage we watched a tank to our left explode from what we guessed was a US fighter attack. The aftershock was so great that we were almost forced from the road.

Later that day we entered Baghdad to the sound of US bombers flying overhead, and finally arrived at the Palestine Hotel, where all the international journalists were staying. Our News Ltd colleague Ian McPhedran had been expelled the day before for breaking the rules by leaving the hotel without permission.

By this stage we had been out of contact for several days, and it was being reported back in Australia that we were missing in Iraq. We were desperate to find a phone, but all our gear had been confiscated and we were under house arrest. The team from Reuters offered to help us out. When we arrived at their room, cameraman Taras Protsyuk and photographer Goran Tomasevic were editing images from the day.

Peter and I started to explain about being captured and driven though the war, but we must have been babbling. Goran grabbed a giant bottle of whisky and in his thick accent simply said: “Drink.”

A few of those did the trick, and we called a very relieved editor Michael Stutchbury who had been fielding calls from early morning radio stations about his missing news crew.

Days later, Taras would be killed by a US tank shell fired into the hotel room as the coalition forces crossed one of the main bridges into Baghdad.

Peter and I witnessed the carnage first hand after the hotel was rocked by the explosion, and rushed upstairs to try to help.

Peter literally had Taras’s guts in his hands as he tried to stem the bleeding but there was too much damage. Taras died on the way to hospital.

Once the Americans arrived in the city, all of the Iraqi spooks left the hotel and we miraculously found our gear in one of the rooms. We were ready to work … sort of. My nerves were shot and simple excursions into Baghdad scared the shit out of me, but I tried my best to keep a brave face and continue.

A tour of what was left of Saddam’s palaces displayed the luxury in which he was living. His soldiers were dead everywhere we looked, some still with their guns drawn, prepared to fight to the death.

After everything we’d been through, one person sticks in my mind from our Iraq assignment. We heard about a little boy who had lost his family and both his arms in a rocket attack on his home. Ali Ismail Abbas was in Saddam City Hospital, which meant we had to head over to the other side of the city, my least favourite place.

Stewart and I were the only ones allowed into his room as the chance of infection to his wounds was so great.

I can still remember with such clarity his high-pitched voice and his confusion over what had happened to him and his family. As well as losing his arms, he had been horribly burned in the attack. We were both in tears as we listened to this brave little boy.

With Stewart’s contacts and Peter’s hard work we were able to get permission for Ali to be airlifted to a Kuwait hospital. Days later we said goodbye at the airfield as he was stretchered onto the plane. Although none of us could have known it then, Ali would go on to start a new life in London and, eventually, a family of his own – at least one happy outcome from a terrible war.

As it happened

Reporter Peter Wilson wrote of being driven under arrest with John Feder through the battlelines in this story published April 7, 2003.

The highway curved gently and suddenly we were in the middle of a battlefield. Our four-wheel drive had just passed through the town of Qurna, where the Tigris and Euphrates rivers meet, half an hour north of the besieged city of Basra.

The mudbrick homes and sandy farmlands that had lined the road for the previous 30 minutes gave way to an open stretch of floodplains, chopped up by mounds of earth to protect tanks. Four or five Iraqi tanks were spread around the field to the left and another couple could be seen to the right, the closest perhaps 50m from the road.

Little other traffic plied this stretch of road but our Iraqi driver, Ali, was not particularly worried – we had already passed half a dozen tanks since leaving Basra and all had been quiet. But suddenly we realised these tanks were actually firing and being fired on. Explosions were going off around them, sending up four-metre fountains of dirt and smoke.

As we accelerated, I asked Ali if they were Iraqi tanks and he nodded tensely. A shell or missile then hit one 300m away, in front and to the left of us. By the time the ball of flame had rolled up from the tank, reaching 20m into the air, we were past it, so the force of the blast thumped into the left of the car from behind. John Feder, sitting in the back left seat, felt it thump the door like a solid impact. In the front right passenger seat, my left eardrum ‘‘popped’’ with the pressure.

Ali was now hunched over the wheel, pushing the Pajero to its limits, and the two other Iraqis in the back were urging him on. This was not a great road to be on, but we had no choice. John and I were under arrest and the three Iraqis were our guards. Our interpreter, Stewart Innes, was in another car with two more guards and we were being delivered to Baghdad for Saddam Hussein’s regime.

60th Anniversary Witnesses to history

For a journalist, no story comes close to this one

The Australian’s former US correspondent was outside the Capitol on the day an angry mob invaded, urged on by Donald Trump.

Simple instructions: ‘Wear a ballistic helmet and a bulletproof vest’

The kibbutzim might have been tiny villages but they were the model, in miniature, for how a future Israel could have looked next to its Palestinian neighbours. By all rights, our reporter shouldn’t have made it there. But he did.

A large Indigenous man on my porch had an unexpected message

The story of a marriage forbidden revealed systemic racism and led to a life-long connection. For our 60th birthday, Hugh Lunn recalls this touching story.

Inside story: How Osama bin Laden hid in plain sight

The Australian’s then-South Asian correspondent had numerous run-ins with armed Pakistani police while covering the story of the decade. But nothing they could dish out could have been worse than having to tell the editor she’d been kicked out.

Cold, furious: The most evil man I have ever met

Getting to interview this man was challenging. He hated ‘gringo’ journalists and had vowed he’d never talk to one again. All of my peers warned me he goes crazy if you ask him about the death squads. But I had to try.

‘Stop the presses’: breaking the news of new pope

When the wisps of white smoke billowed from the Vatican chimney, The Australian newspaper had long been put to bed. Our correspondent couldn’t wait another day to file. We share this story for our 60th anniversary.

The first big yarn to take a toll on Hedley Thomas

Being sent to cover the bloody overthrow of the communist regime in Romania was a seminal experience for a young reporter who would become one of The Australian’s most highly acclaimed journalists.

At the scene of the story that gripped the world

Reporting from the muddy mouth of the cave complex as a monsoon loomed, it felt crushingly inevitable we would be relaying grim news about a trapped junior soccer team. But then came a sudden turn.

John Feder has worked as a photographer for News mastheads The Australian, the Sunday Herald-Sun and the Sunday Herald over the past three decades. He's covered wars in Iraq and East Timor, federal politics and the terror attacks on 9/11, which happened while he was travelling with Prime Minister John Howard in Washington. Some of John's most renowned sports photos include Cathy Freeman wrapped in the Australian flag at the Commonwealth Games and Nicky Winmar defiantly gesturing to an AFL crowd

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout