Meet the women tackling art’s biggest problem

Addressing an historical gender imbalance on the walls of our most prominent art institutions is finally at the top of the cultural agenda.

It was 2019, just a few months into Natasha Bullock’s role as its assistant director of collections and exhibitions, that the National Gallery of Australia was compelled to address a very large elephant in its portrait room. The gallery’s vast collections were audited in collaboration with The Countess Report, an independent benchmarking initiative that monitors gender equality in the Australian contemporary art sector. The findings revealed just 27 per cent of the works it acquired between 2014 and 2018 were created by female artists. Works by women also represented just a quarter of its Australian art collection.

This story appears in the August issue of WISH, out on Friday, August 4 with The Australian.

This was the catalyst for Know My Name, a program developed to address gender inequality and increase female representation in the gallery’s collections. Early in the program’s development, Bullock and her team realised that while exhibitions celebrating female artists were steps in the right direction, tackling the organisation’s public-facing gender imbalance wasn’t enough. “It needed to be deeper than representation and cultural production,” she tells WISH. “It needed to be about deep structural change, because we’re leaning into hundreds of years of bias and discrimination.”

This revelation led to the formation of the Gender Equity Action Plan working group, which under the direction of Bullock, has resulted in some monumental shifts not only within the NGA’s collections and acquisitions, but behind the scenes, too. While the 2023 Countess Report is yet to be released, the 2019 report also revealed some alarming statistics about the gender imbalance in Australian art. It found that while 71 per cent of art degree graduates were female, they accounted for just 33.9 per cent of artists represented in state-run galleries and museums; a three per cent decline from 2016.

It also highlighted that despite holding more positions in the industry overall, just 12.5 per cent of chief executive and director roles in state-owned galleries were held by women. Four years on, Bullock proudly confirms that the action group’s endeavours have led to significant change within the organisation. “We have met our gender equity targets in artistic programming, in collection development, in publishing, programs and in education,” she confirms. “It’s really become part of the DNA in our organisation, and it really is starting to be cemented strongly into our mission, which is to lead a progressive cultural agenda, and I think, as the NGA, it’s our responsibility to lead with these social enterprises.

”Meanwhile, down in Melbourne there’s an anomaly in the National Gallery of Victoria’s 16th century Italian art collection. It’s an oil on copper painting, depicting St Catherine of Alexandria’s consecration to Christ. The theme is typical for its period, and the artist’s skill is both exceptional and comparable to works by the country’s great artists of the time. But look to the left of its gilt frame and you’ll discover what makes the 1575 work, Mystic Marriage of St Catherine, so unique – it was painted by a woman.

“Lavinia Fontana was an Italian painter and was, and still is, widely known as the first female professional painter artist,” explains Donna McColm, NGV assistant director, curatorial and audience engagement. “She had 11 children, her husband looked after the children and helped manage the studio so she could be the breadwinner.” Having been painted in an era when female representation in art was confined to subject matter, Fontana’s work – which was acquired by the Felton Bequest for the gallery last year – is both extraordinary and rare. With the general scarcity of historic artistic works by women, bringing absolute gender parity to the NGVs historical collections – or any of the world’s notable museums and galleries for that matter – is an impossible task. “Considering the very long histories of many museums you’re starting from a very difficult position …” McColm explains, “because a lot of women artists at the time perhaps were not recognised for their work.” It’s a challenge the gallery has been tackling for the past decade. “The changes in our collections look like they’re slow, but actually each one of those stories requires so much research, and finding the acquisitions, bringing them to the floor and making them possible takes a long time,” she says. “Much, much longer than by a well-known male artist.”

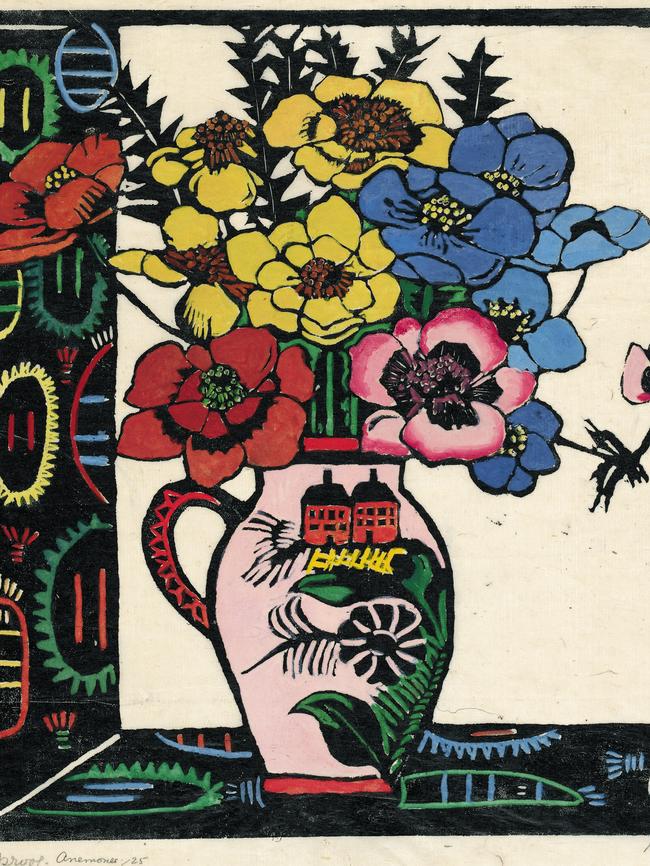

This dilemma was front of mind during the establishment of the Art Gallery of New South Wales Sydney Modern Project. The team, faced with curating historical collections dominated by works of male artists, looked at ways to give female artists a significant presence within its spaces. “We were so aware of this narrative, and this big idea to achieve that we really worked with the curatorial team to place women in significant positions,” says Maud Page, AGNSW deputy director and director of collections. “For example, the beautiful Portrait of Lucie Beynis by Grace Crowley begins the whole discussion around abstraction and cubism in our 20th century galleries.” The NGV and AGNSW are just some of the galleries and museums across the country – and the world – shedding light on art’s historical disregard for female talent while simultaneously putting in place measures to ensure the mistakes of the past are not repeated.

The creative synergy between visual arts and the clothing and beauty industries has led to a rise in commercial funding and patronage of arts initiatives, and the establishment of art centres and private museums by some of the world’s leading fashion and jewellery companies. From the Cartier Foundation for Contemporary Art to the Fondation d’entreprise Hermès, supporting the arts is now the norm, rather than the exception, among Europe’s luxury houses, and as such, an increase in awards and scholarships for female artists is on the rise. In December, the NGV will present the work of UK designer Bethan Laura Wood, the second recipient of its Women in Design Commission, following its successful launch in 2022 featuring Mexican architect Tatiana Bilbao.

The five-year initiative, in partnership with Australian beauty brand Mecca, was designed to improve female representation in the NGV’s Collection of Contemporary Design and Architecture. “Her [Bilbao] project was a really incredible immersive installation drawing attention to the undervalued nature of domestic work in Mexico but also broadly,” says McColm. Bilbao’s work (and Wood’s to come) is now a permanent part of the collection, something McColm says is vital because “now, from the beginning, these female designers are written into history. We’re doing that work as it’s happening, which is really exciting, so we’re not in danger of missing these extraordinary stories”.

Similarly, the AGNSW has formed a partnership with Swiss skincare house La Prairie on the annual La Prairie Art Award, which has championed the careers of artists Atong Atem and Thea Anamara Perkins, who was this year's recipient.

London’s National Portrait Gallery, which recently reopened after renovations that began in 2020, is also going down this path. The institution, with the support of the Chanel Culture Fund and its appointed curator Flavia Frigeri, has spent almost three years working on Reframing Narratives: Women in Portraiture, a project aiming to increase representation of female artists within its collection. Yana Peel, global head of arts and culture at Chanel, says the partnership has resulted in a 129 per cent rise in the representation of female artists on display in its post-1900 galleries. It was also readdressing historic gender imbalances and those who “have previously been left out of the picture”. “As the gallery reopens, 48 per cent of portraits on display will be of women,” Peel adds.

Art institutions have a significant role to play in the restoration of a more gender equitable visual arts industry, but Bullock believes systemic change can only take place if these conversations take place at home, in schools and outside the gallery walls. “We can’t just be about talking to ourselves in the art world,” she says. “Our public’s really important, our audiences are really important.”

This story appears in the August issue of WISH.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout