The Iranian-born Melbourne-based photographer on her first exhibition with the AGNSW

Ahead of her first exhibition at the AGNSW Iranian-born artist Hoda Afshar is using the power of photography to dramatically bring into focus some of humanity’s most profound struggles.

There is a man and a woman admiring a portrait on the wall, standing and chatting. It is a warm summer’s day in Sydney and the Art Gallery of NSW’s new building is packed. But this man and woman are no ordinary visitors, as passersby soon realise. They stop, form a crowd and film on their phones. They know they are witnessing something extraordinary.

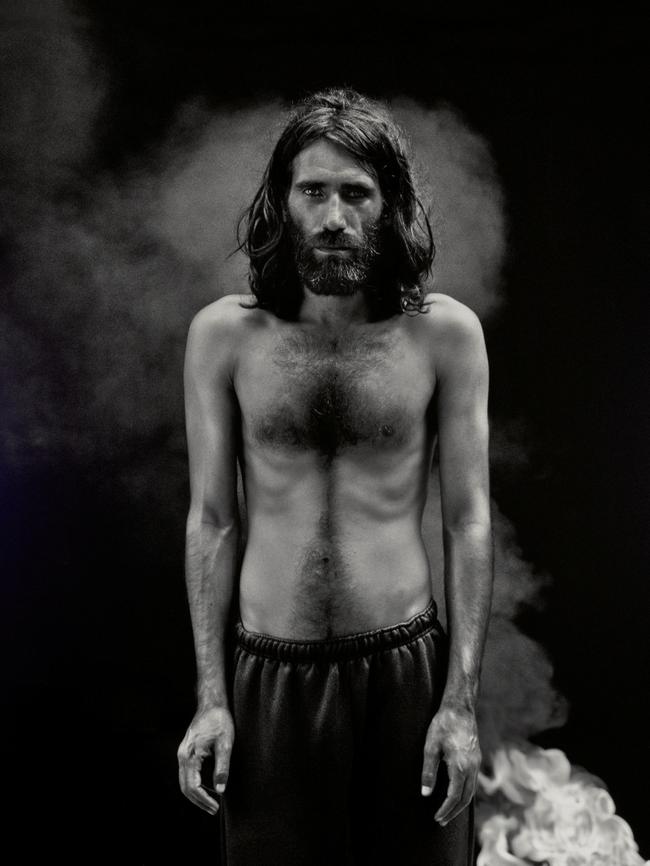

The man is the subject of the portrait they are standing before and the woman is the artist who captured it. This is the first time they are seeing it together since 2018. They are refugee and journalist Behrouz Boochani, imprisoned on Manus Island for six years, and Iranian-born photographer Hoda Afshar, who smuggled her camera under a false bottom in her suitcase to take pictures of stateless men detained on the PNG island by Australia’s harsh border protection laws. She wanted the public to see them.

Out Friday: Don’t miss your copy of the annual art issue of WISH

And it worked. The haunting photograph – part of a series called Remain – has won critical acclaim and several awards, been exhibited around Australia and the world and seen by thousands of people. Boochani, who also painstakingly penned a memoir via WhatsApp messages while on Manus Island, managed to get to New Zealand after the detention centre closed but had been barred from entering this country. That finally changed when he was given permission to come here in January for a book tour and landed in Sydney. Afshar, who is based in Melbourne, was in town for a meeting.

“We both went to see the photograph together and he was just mesmerised by it, and he kept asking me, how did you do this?” Afshar recalls. “He was saying he had seen it so many times before but being there with me, seeing it in person, was an entirely different experience. It was like seeing it for the first time. That was one of the most special moments I have ever experienced with my work. And as we were standing there, having this long conversation about it, we turned around and there was this huge crowd behind us as people realised it was Behrouz looking at his own portrait. People were taking pictures with their mobile phones and we realised, wow, we have an audience.”

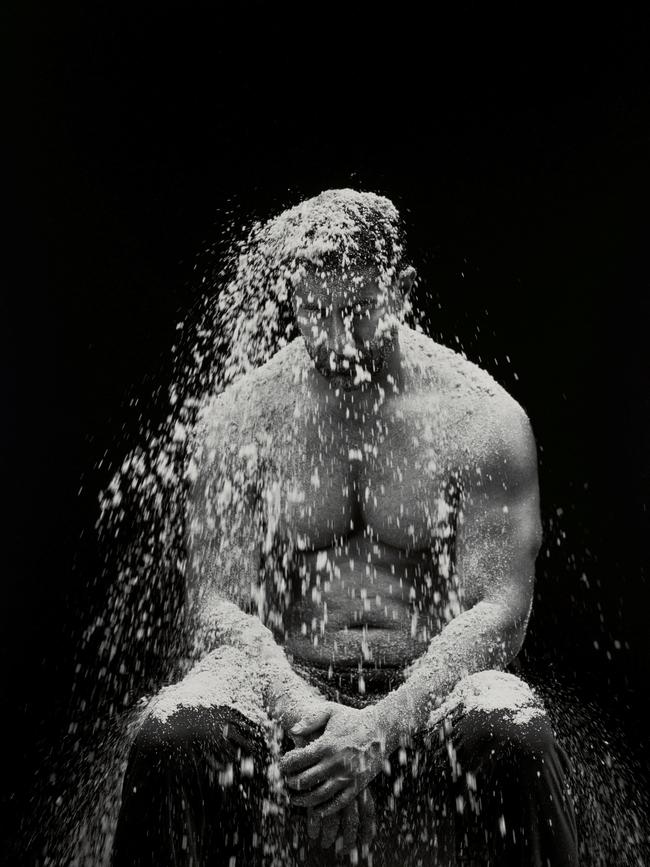

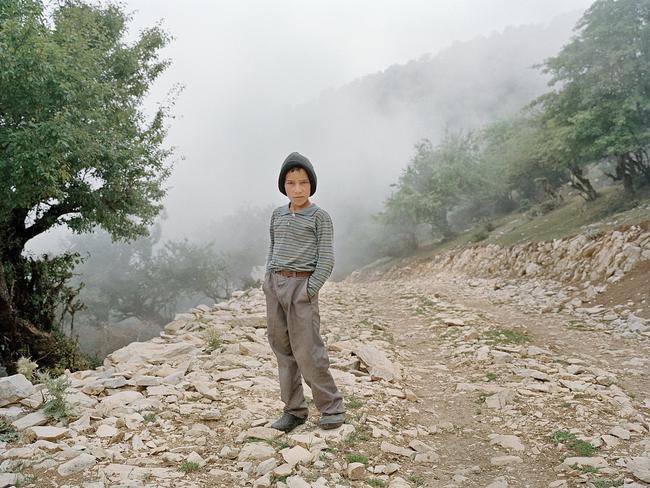

The photographer is about to have a much bigger audience as she prepares to exhibit the first major survey of her work at the Art Gallery of NSW in September. Hoda Afshar: A Curve is a Broken Line will showcase the past decade of her biggest projects, from Remain to a series of work started in 2014 about her homeland, Iran, called In the exodus, I love you more, and one created in 2020 about whistleblowers titled Agonistes (which means struggle in Greek), as well as more recent work focused on the extraordinary bravery and theatre of the female-led uprising in Iran.

“Hoda uses photography to really draw attention to particular narratives that may be almost hiding in plain sight, things that we might not be attuned to but that are happening under our noses,” explains Isobel Parker Philip, senior curator of contemporary art at AGNSW. “She asks that we not only address those realities but also think about the people whose lives are affected, and she really amplifies their rights and their humanity. She uses the medium of photography as a form of activism as much as an artistic inquiry.”

Afshar first saw Boochani on television protesting about his treatment at the hands of the Australian government in 2018. The Kurdish-Iranian journalist fled his home and desperately tried to seek refuge in Australia via a boat from Indonesia. He was sent to the detention centre on Manus Island in 2013, joining more than 1000 male refugees left stuck and stateless by our unforgiving immigration policies.

“He was pleading, in broken English, for help from the Australian people. He is a Kurdish man and my dad is a Kurdish man, and I felt this deep urge that I should do something and I should use my platform to raise awareness because I can speak his language,” Afshar explains. “Through some advocate friends I got in touch with him, and we planned an entire trip for me pretending to be a tourist in Port Moresby. And then I had to apply at the border. I hid all my camera gear at the bottom of my luggage with another surface on top to hide it, and locals picked me up from the airport.”

-

“The men on Manus Island were being depicted as dangerous criminals, and I wanted to bring the stories and identities of the individuals into focus”

-

The photographer was on Manus Island for nine days. There she shot video and multiple photographs – all on film as she loves working with film – and was watched the whole time by immigration officials, who thankfully did not throw her off the island. (Afshar believed they didn’t take her seriously and thought she was just a young activist hanging out with refugees.)

That couldn’t have been further from the truth, as Afshar went there with a deliberate goal. She wanted to change the public perception of refugees from that of nameless, faceless people who just wanted to come to Australia “illegally” and would do anything to get here. “The men on Manus Island were being depicted as dangerous criminals, and I wanted to bring the stories and identities of the individuals into focus so the public could see who these people were who the Australian government was doing this to with inhumane border protection laws,” she says. “My intention was to shatter the image of a typical refugee as lacking in agency or autonomy. And I did this by getting them to be actively involved in making the work.”

She started by asking the asylum seekers to come up with something in nature that could work as a background and props, as she knew she would not have access to anything else. Boochani wanted to put an octopus on his head – to represent the Australian government – but the local fisherman weren’t able to find any despite spending two days looking. Boochani’s plan B was to use fire.

So Afshar photographed Boochani in the water with smoke billowing in the background. The haunting and confronting black and white image depicts the refugee standing, naked from the waist up, with long hair and beard, arms hanging down. Afshar later told Boochani she believed the portrait showed “your passion, your fire, and your writer’s hands” and symbolised his resistance.

“Behind the scenes of that one image there were 10 people involved; it was like theatre,” she explains. “Someone was making the fire, there was someone throwing water towards him, two people were holding the backdrop, it was quite amazing. Someone was holding the reflector. They were all these refugees helping to make each other’s portraits.”

Afshar, who turns 40 this year, was drawn to helping Boochani and the other refugees caught in the net of Australia’s asylum-seeker policy not only because her dad was Kurdish, but because she’d also left her home country of Iran. But her journey and Boochani’s were very different. As Afshar describes it, she was privileged to be able to come to Australia in 2007 in search of a freer life. She had just finished her fine arts degree, and was being encouraged to head overseas by her parents to build a better future. She was thinking of Italy but decided to come to Australia for her partner at the time.

“That was 16 years ago,” says Afshar. “It is hard as my family are back home. It never gets any easier. You think after all that time it would get easier, but it doesn’t. You get used to it but you never get over being separated from your homeland and family. But I chose to leave everything behind to be able to do what I do and live my life freely and respected as a human being.”

Afshar was born in 1983 in Tehran, four years after the Iranian revolution installed an Islamic Republic and three years after war broke out between Iran and Iraq (that lasted until she was five). She says her earliest memories of childhood were of growing up in war, of listening to the radio for air raid warnings, of feeling scared hearing the planes flying overhead. Of her parents grabbing her and her sister and rushing them down into the basement, singing to them to keep them distracted.

“The spirit of war was everywhere,” she recalls. “I remember sitting on my parent’s shoulders, putting tape on windows just in case we were bombed so the windows wouldn’t explode. All these memories stay with me still to this day. But with the naivety of being a child, I don’t think you really get the depth of the disaster. I think for parents who are going through that period, having to protect their kids, that is more traumatising. I remember the fear in my parents’ faces and bodies.”

But what was also happening during her childhood was Iran’s transition from a secular monarchy to an Islamic Republic. This influenced every aspect of Afshar’s life, from her schooling to what was on television – every aspect of existence outside her home and the sanctuary created by her parents, who grew up in a less religious 1970s Iran. “The government was introducing a new national identity and this started by controlling women’s bodies,” Afshar says. “This is historically the case with all power systems; the level of freedom in society can be measured by the freedom of women. The more they want to control the society, the more control they place on women’s bodies.”

It also meant that as a child she inhabited two conflicting worlds: the one inside her house with her family and the one outside under the strict Islamic regime. There was also always the fear of being arrested by the morality police every time she left the house, gave the wrong answer to a question, got caught illegally meeting up with her friends. Everything she did carried so much risk. And schooling for her consisted only of studying the Koran, and learning Arabic, the history of the Iranian leaders and religion.

“Imagine growing up with your parents telling you don’t believe anything the school tells you,” she says. “When you go to school, if they ask whether your parents cover their hair, just lie. If they ask you whether your parents drink, say no; have parties, say no; say your prayers, say yes we do. You are trained in how to become a professional liar, to protect your loved ones. When I think about it now it was just crazy; how much of a burden can you place on the shoulders of a child?

“Everything was risky. So the choice was to stay and live under the oppression or leave and set yourself free, which meant leaving everything you loved behind. Some people made that choice and some people didn’t. Some people had the privilege of being able to make that choice but most didn’t.”

Afshar was just 23 when she decided to leave Iran after studying photography at university. Her first love was actually theatre, but she didn’t get into the course. All her early work was photographing her theatre friends, which laid the groundwork for the way she approaches her art now.

“It is something that you can see in my work with photography, and that is treating documentary subjects quite theatrically and looking at the world as a stage for performances,” she says.

-

“I think unconsciously I am trying to make sense of human trauma and suffering through making work about others to understand my own predicament”

-

She wanted to be a war photographer but her mother talked her out of it, so instead she set her mind on documentaries. She worked for a newspaper, where she spent 12 months with a group of women on the outskirts of Tehran who were selling their bodies to get by. She documented the underground parties of her friends even though she knew the images would never be shown. “One of the reasons I loved photography originally is that it gives me power to photograph the unseen and the hidden,” she tells me. “That is something that remains in my work to this day.”

Parker Philip says one of the most significant aspects of Afshar’s art is that she does approach subjects that have traditionally been underrepresented or misrepresented.

“A lot of her work is quite explicitly about the politics of representation and the way that we are habituated into seeing the world a particular way,” she tells WISH. “And a lot of that is mediated through images that we are drenched in every single day, and that really does condition the way we see the world around us.”

The other striking thing about Afshar’s work is that she photographs such heavy subjects, from refugees to wars around the world (while stuck in lockdown in London, the artist created another body of work by collecting pictures of war and destruction from social media) and the work she has been doing highlighting the incredibly brave women burning their hijabs in Iran. I ask her how she copes with this.

“I make work about things I feel personally and historically connected to, and something that I can make sense of. I am not removed from it fully. My life personally is very much affected by the same tragedies and government policies,” she explains. “I think unconsciously I am trying to make sense of human trauma and suffering through making work about others to understand my own predicament. And also, finding resilience and strength in people who struggle in those situations is what gives me hope for humanity and life. I find it often in those places more than anywhere else.

“I have sat in refugee camps, listening to refugees sing and tell me music was the only thing that got them through years of imprisonment, that music was the only thing that gave them hope to survive. Those moments and that exposure to such resilience in humans is what gives me meaning in life.”

I interview Afshar in her Melbourne apartment, spending the afternoon chatting over excellent coffee, dates and dark chocolate. We sit around her dinner table, stacked with books on one side and a box-like medium-format camera she is using for her next project.

She is creating a series of new work for her upcoming AGNSW solo exhibition focusing on the fearless women protesting in Iran by refusing to wear headscarves since the brutal murder of Mahsa Amini in September last year at the hands of Iranian authorities for wearing her hijab “improperly”.

“When I see the women in Tehran on the streets without headscarves, it really does give me shivers, because they are the bravest women I have ever known,” Afshar says, passionately. “Because we all have seen what the government does to women. It is not just the simple punishment, it is torture and murder. But they have collectively decided to refuse to wear it. It is extraordinary.”

The artist is looking at the imagery of the protests coming out of Iran and seeing the way the women are using symbolism to communicate their feelings, needs and desires. This includes such things as plaiting their hair and the use of birds. “The idea of a female-led revolution and uprising and the aesthetic of it and how different it is from previous revolutions,” Afshar says of her project. “It is so fascinating that they are staging all this to create very poetic images to talk about a possible revolution in the making.”

Afshar really does hope it will eventually turn into a revolution in Iran. She says that such uprisings historically take time. “If it does happen at some point in the future, it will be the first feminist revolution in the world,” she says. “Of course the Iranian struggle goes beyond women’s struggle, but everyone from this point believes that they will only free themselves if they free their women.”

And as an artist, she just hopes she can contribute and be a “tiny part of the process” of change against unjust governments and policies through highlighting the struggle of unseen subjects, such as the women protesting in Iran and the desperate refugees imprisoned for years on Manus Island.

“Hoda draws people in to care,” says Parker Philip of the power of Afshar’s work. “She is dealing with incredibly heavy and political subjects, but there’s an intentional poetry to the way she works with them. She is directly addressing not just the violence but also asking, how does art effect change? It effects change if people care and so that emotional tenor of her work is incredibly important.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout