Thea Anamara Perkins, artist

The granddaughter of Charles Perkins, artist Thea Anamara Perkins, is drawing on her proud lineage to create artworks inspired by memory, photographs and story.

A few months ago, Sydney artist Thea Anamara Perkins was sifting through a box of family photographs and came across a picture of herself when she was a child of preschool age. It shows her at what appears to be a family gathering, and she has the tired expression of a child who’s probably had too much excitement for one day. She’s wearing a T-shirt on which is printed a map of Australia, in the colours of the Aboriginal flag – black, yellow and red.

Thea’s mother, Hetti Perkins, says the picture was taken at a family barbecue for what would have been Thea’s third birthday. In a commission for WISH, Thea, 29, has transformed the snapshot into a work of art.

An artist who is steadily gaining national recognition through exhibitions and awards, Perkins works with the visual language of photographic images – their captured moments of intimacy or unguarded expression, their sometimes slightly off-centre composition and uncorrected colour. Using these images as base material, she translates them to acrylic paint and board – not as exact replicas, but imbued with the warmer, softer-edged tones of memory. Her recall of the long-ago birthday party may be hazy, but the image of it in her mind’s eye is “quite beautiful, impressionistic almost”.

“I’ve always liked the idea of going into the archives, from the perspective of delving into memory,” she says. “I find it’s a good way of giving myself space to look at my own life and examine where I’ve come from, what was happening at the time.

“Archival photos are often film photos, and I think it has a nice harmony with memory – when you remember things you do kind of embellish them, and bring out different colours, and brighten them.”

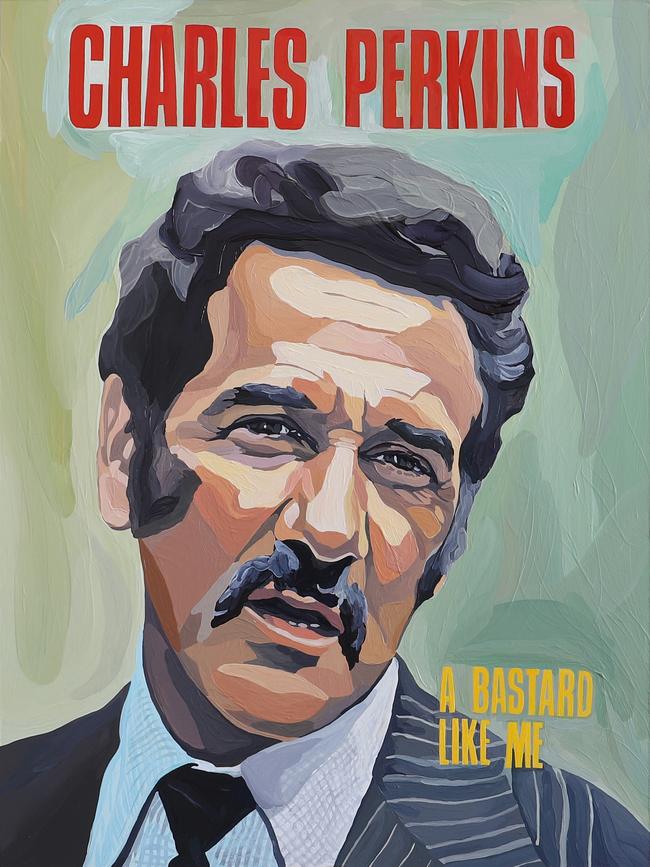

Self-portraits are not the only subject of Perkins’s art. She also makes portraits of other artists, family members and prominent people in the Aboriginal community. Her grandfather was the Aboriginal activist, public servant and community leader Charles Perkins, and a portrait of him is Thea’s entry for this year’s Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards, to be announced in August.

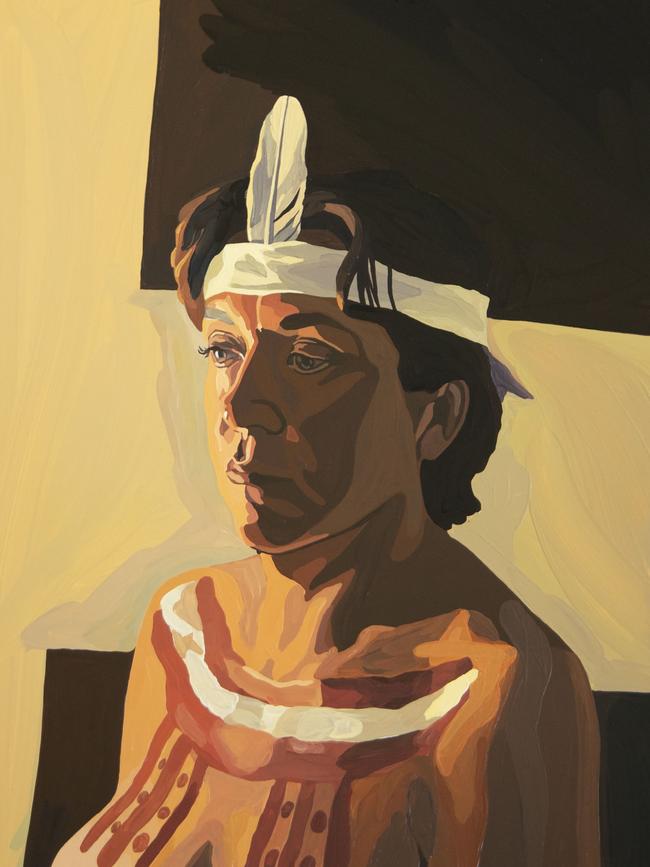

For the Archibald Prize, she has entered a portrait of her aunt, filmmaker Rachel Perkins, showing her wearing the ceremonial ochres of the family’s Arrernte heritage. She has been an Archibald finalist twice before with portraits of her paternal grandfather, Gadigal elder Charles “Chicka” Madden, and of multidisciplinary artist Christian Thompson – an inaugural recipient of the Charlie Perkins Scholarship, which enabled him to complete his doctorate at Oxford University.

“I’ve always had a compulsion to look at the family archives,” Thea says. “When I want to talk about my Aboriginality, it’s to talk about it through a lens of what I know. So it’s looking through these documents to talk about a wider experience.”

Thoughtful and quietly spoken, Perkins wears her multigenerational heritage of a family deeply involved in Aboriginal culture and community lightly. WISH is speaking with her along with her mother, Hetti Perkins, a respected art curator, and her aunt, Rachel Perkins, in the backyard of Rachel’s inner-Sydney home. The conversation turns around family, identity and culture – its manifestation both as language, custom and ceremony, and as the contemporary practice of making and presenting art, whether painting, curating or filmmaking.

The family’s heritage is Arrernte, from central Australia, and Kalkadoon, from around Mt Isa. Thea’s great-grandmother Hetty was an Arrernte woman and a matriarch of the community around Alice Springs. Her son Charles was born on a table at the former Alice Springs telegraph station in 1936. As he recorded in his memoir A Bastard Like Me, mixed-race children, of which he was one, were in accordance with official policy separated from traditional tribal people. He met his grandmother only once.

Charles, or Charlie, had an extraordinary career, first in representative soccer and then, after his graduation from the University of Sydney – he was the first Aboriginal man to earn a university degree – as an activist and public servant. A central episode in his life story is the famous Freedom Ride he organised in 1965. He led a busload of university students on an adventure to north-western NSW, with the idea that they would expose and overturn racism wherever they found it.

After a protest outside the Walgett RSL Club the Freedom Riders were run out of town (and off the road). In Moree they staged a demonstration outside the swimming pool, which barred or restricted entry to Aboriginal people. Perkins and his collaborators were pelted with tomatoes and eggs but they held firm and the police opened the pool.

The episode is told in a chapter of A Bastard Like Me, a small hardcover volume published in 1975. The cover photo shows Perkins wearing the fashions of the day – a handlebar moustache and a wide-lapel suit, and a tie bearing the crest of Sydney University.

Thea was only eight when Charles died of kidney failure in 2000 at the age of 64. She has used the image of her grandfather from the cover of his book – including his name and the title – for her portrait, which she has called A Bastard Like Me.

“I have fond memories of my grandfather – playing with him and spending time with him,” she says. “I remember him always working; he was very driven. But just the most wonderful person... I remember the political stuff, going to marches with him, and feeling his real passion.”

Hetti says: “Dad was a total pushover with the grandkids. With his kidney failure and those things, he said he just wanted to live long enough to see his grandchildren. He was very grateful for that.”

She looks at her daughter, and recalls how Charles would carry Thea with him when he went to meetings or took his grandchildren to play at the beach. “His favourite thing was to go for a coffee, meet Tony Mundine up at Bar Coluzzi, and he’d always have a couple of grannies [grandchildren] that he’d drag along with him,” she says. “He’d take them to the park and down to Bondi Beach – we all lived at Bondi at that time. People say, ‘I remember your dad – he was always here with the grandkids.’ That was a real joy of his life. But he was working all the time.”

She recalls how Charles panicked when Thea, still a toddler, became critically ill and had to be rushed to hospital.

“Thea had viral encephalitis, or something in the brain – it was extremely dangerous,” she says. “We were at our place in Bondi and Mum and Dad were staying there. Mum and I were in the lounge room with Thea and keeping an eye on her. At three in the morning Dad got out of bed, came running in, saying ‘Get in the car, we are going to the hospital now.’ It was horrific, and Dad was going off. [At the hospital] they said, ‘We are going to have to sedate your father, because we’re trying to do our job and he’s screaming and all over the place.’”

Thea grew up in a talented, creative family. Her sister, Madeleine Madden, is an actress who has appeared in episodes of Redfern Now, the hit ABC TV series produced by Rachel’s company Blackfella Films, and in features including Around the Block and Dora and the Lost City of Gold. Her brother Tyson Perkins is a cinematographer whose work includes video clips, commercials and the Australian Chamber Orchestra’s StudioCast online performances.

Culture, in the sense of being active in a community, was a fact of life in the politically motivated Perkins family. But it wasn’t a given, Hetti says, that she and other members of the family would go on to have successful careers in the creative arts. It was Hetti and Rachel’s mother, Eileen – now 82 and living on the NSW Central Coast – who developed an interest in promoting the visual arts. In the 1970s the family lived in Canberra, where Charles was working for the Department of Aboriginal Affairs, later rising to Secretary. Eileen, who is not Aboriginal, opened a gallery in the family garage to display Indigenous art.

It was Hetti and Rachel’s mother, Eileen – now 82 and living on the NSW Central Coast – who developed an interest in promoting the visual arts.

“She decided to start her own little gallery, mainly so that diplomats and general visitors could come and see Aboriginal art in Canberra,” Hetti says. “And also for us: she wanted us to grow up around it and to experience it. She did all sorts of things – fashion parades with the beautiful Tiwi fabrics that were being made then, and with Aboriginal models. There was that level of creativity.

“One of the things that we were raised with – the same mantra that Dad was raised with – was if you’re not doing the right thing, you’re doing the wrong thing: ‘Just do the right thing.’ I think we felt a keen responsibility to our community – you want to be part of that community and do what you can.”

Hetti went on to be a prominent curator and writer on Indigenous art. Most notably, she was curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art at the Art Gallery of NSW for 13 years. Some of her personal and professional interest in the visual arts must have rubbed off on her daughter.

“I was a single working mum when Thea was a baby, and she would come to work with me at the art gallery,” Hetti says. “She would be in her baby bucket and the installation crew would wheel her around with the art. She has been exposed to art all along.”

Thea enrolled at the University of NSW Art & Design school in Sydney but deferred her studies. Within a few years she was having solo exhibitions at galleries including Firstdraft in Woolloomooloo, an exhibition space for emerging artists where she is now a member of the governing board.

“I never felt pressure, and art was always a way I have expressed myself,” she says. “So it came quite naturally that I would be an artist… When I do paint a lot of it is self-taught, being in the studio and figuring out different ways to use paint. I love experimenting.”

She attracted notice last year when she won the Alice Prize at the Araluen Arts Centre in Alice Springs. Her winning entry was a portrait of Rachel and Charles at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra in the late ’70s. In the painting, also based on a treasured family photo, Rachel is eight or nine and wearing a yellow T-shirt hand-drawn with an Aboriginal flag and the words “Land rights”, and appears to be having a confidential word with her father.

Rachel recalls: “I remember making our T-shirts with textas, and making placards, preparing for the demos. It was about Queensland and their bad track record on Aboriginal land rights, that was the focus of it. I was standing a little way away from Dad, and I heard some people running him down. I was like, ‘I’m going to tell Dad.’ And someone took the photo at that time. You want to be helpful as a kid – I was giving him the lowdown; that’s what’s happening in that photo.”

The judge of the Alice Prize, Rhana Devenport, director of the Art Gallery of South Australia, praised Thea’s “exquisite jewel-like embrace of painting and its potential” in an image that evokes both the tender relationship of father and daughter and a powerful political moment.

In recent years Rachel has been helping the women of the Arrernte community record their songs and ceremonies on video. The video record is not intended for wider distribution but to help maintain the continuity of cultural knowledge for future generations.

Thea, Hetti and Rachel have each experienced the Arrernte women’s ceremonies and had their bodies handpainted with ochre. “It was very beautiful,” Thea says. “We have this deep and strong connection to place, especially when we go up there… It’s that idea of experiencing the divine, connecting with something beautiful and ancient, being painted and having it on skin. It’s really powerful to be participating in that.”

Thea has painted a portrait of Rachel wearing the ochres and ceremonial designs of the Arrernte women. Unlike many of her other paintings that are based on photos, this one was done after life sittings, as required by the rules of the Archibald Prize. The portrait glows with the warm colours of morning or afternoon sun, and shows Rachel in a proud pose, wearing the white and umber ochres across her chest, and a white feather at her forehead. The portrait combines the visual symbols of Indigenous Australia with some of the ambience of orthodox icons.

“It’s a very tangible expression of culture – you dance your songs, you get painted up,” Rachel says. “It’s like another world, but it’s all going on, up home.”

Thea, her mother and her aunt each have ongoing artistic projects. Hetti is the curator of the fourth edition of the National Indigenous Art Triennial, opening at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra in November. The program will extend beyond the visual arts and include dancers, writers and performing artists, each exploring the idea of ceremony.

“It’s the idea of the world’s oldest continuous cultural tradition, and ceremony that has been practised for so long, and which is a feature of the present day – often in unexpected ways,” Hetti says. “It could be the act of painting, and how it channels ritual and ceremony.”

Rachel recently has finished filming a second series of Total Control – the political drama with Deborah Mailman and Rachel Griffiths – and a new series about books and writers hosted by Claudia Karvan. Another new series, due to screen later this year, is a three-part documentary for SBS called First Wars, about frontier conflict between Indigenous people and European settlers. “Up in the Kimberley they were still shooting people in the 1920s and ’30s,” she says. “We’re working with historians and descendants of the communities, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous.”

Thea continues to draw inspiration from her family, from the emotional and photographic record of memory, and from the ancient culture of which she is a young custodian. As her portfolio of portraits grows, and wins accolades, she says she wants to depict Aboriginal people in ways that captivate and inspire the viewer.

“As Aboriginal people we all stand on the shoulders of giants; it is a huge legacy,” she says. “People are so receptive to portraiture, and it’s a strong way of talking about really complex ideas. Through representing people, it can contain all of the things that I want to say about Aboriginal people – being brilliant and bold and beautiful, and doing these amazing things.”

Thea Anamara Perkins’s solo exhibition, Shimmer, will be at N Smith Gallery in Sydney’s Paddington from June 8 to July 3. nsmithgallery.com

Matthew Westwood is The Australian’s arts correspondent

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout