Intrepid women, SH Ervin Gallery, Sydney: taking flight to Paris

Several unconventional Australian women artists lived in Paris between the Edwardian period and World War II.

Catherine Deneuve’s criticism of the Me Too movement in the US, together with 99 other French women, reminds us how much more open-minded France is about sexuality than America, which never really seems to have emerged from the 19th-century dread of a dark and ultimately untameable physical and psychological drive.

The long American love affair with psychotherapy, and even the so-called sexual revolution, seem to have had no more than a superficial effect on ingrained attitudes.

And while earlier versions of feminism promoted the liberation of female sexuality, the current generation is reviving a puritanical horror of sex, now implicitly characterised as a dangerous and inherently predatory male instinct of which women are inevitably the passive and helpless victims.

But what is equally striking is the American propensity for moral histrionics, the new manifestation of the old revivalist religious impulse to confess one’s sins in public and beg the forgiveness of the Lord while the ecstatic congregation chants in unison. This is what makes the Me Too movement so quintessentially American: there was indeed abuse and repugnant exploitation, but also undeniably hypocrisy and connivance when these were expedient; and then when the scandal broke there was a panicked rush to confess and to accuse and to call for the public stoning of sinners.

But where, one may wonder, was the outrage for thousands of women raped and murdered every year in brutish domestic violence? Or for women put to death in so-called honour killings, or genitally mutilated in Third World countries? Or for Aboriginal women and children abused in dysfunctional indigenous settlements? No, it was not until it was revealed that Hollywood princesses had been exposed to unseemly advances that hysteria broke out to distract us from the extent of corrupt consent, or worse.

Objections by Deneuve and her friends — and more recently Germaine Greer — have predictably been met with more breathless indignation from the harridans of self-righteousness, but in reality the French have long had a more realistic view of sexuality and a more nuanced understanding of the relations between men and women. Both sexes experience desire and seek companionship and both can have agency in the domain of love.

French women know what they want and are mature enough to negotiate the terms of their relations with men, without the cloying moralistic kitsch of American sexual politics.

Paris was already a haven of sexual freedom in the 19th century, largely, although not entirely, escaping the wave of puritanism that overcame Britain and America in the age of Queen Victoria. It was also the capital of modern art from the mid-19th to the mid-20th century, and so it was hardly surprising that it became a centre for the artistic and the unconventional, including the Australian women artists surveyed in this exhibition, who lived in Paris for the most part between the Edwardian period and World War II.

Many of these women were lesbians or bisexual, some perhaps asexual or merely repressed; a few were married but most remained childless. And although attitudes were far more naive before vulgarised forms of Freudian thought had permeated popular culture — Australian society was full of spinster ladies living with their female companions, as well as a multitude of unmarried gentlemen — the opportunities for openly expressing unconventional sexuality were limited.

In Paris, on the other hand, homosexuality was largely tolerated and there had long been an active lesbian community, among which two of the most prominent women were the American Natalie Clifford Barney (1876-1972) and her beautiful English lover Renee Vivien (1877-1909), who wrote sapphic poems in French and whose descent into alcoholism and self-destructive sadomasochistic behaviour was evoked by Colette in Le Pur et l’impur, published years after its subject’s death.

One of the most interesting Australian expatriates is Agnes Goodsir (1864-1939), who studied in Bendigo at the School of Mines before moving in 1899 to Paris, where she lived for the rest of her life. A number of her most memorable pictures are portraits of her handsome, androgynous girlfriend Rachel Dunn, known as Cherry. Here she is represented by three paintings, including La femme de menage (1905), a fine composition in the vein of modern neo-Spanish tonal realism that inspired Ramsay and Lambert at the same time.

Another significant artist is Janet Cumbrae Stewart (1883-1960). Like most of these women artists, she came from an upper-middle-class family, which allowed her to pursue an independent life. She studied at the National Gallery School and exhibited successfully in Australia and overseas before moving to Europe in 1922, living in France and Italy for 17 years before returning to Australia on the outbreak of World War II.

Cumbrae Stewart lived in Europe with a Miss Argemore ffarington Bellairs, known as Bill; in her touching self-portrait at the age of 28 or so, in the National Library (1911), she represents herself in contrast as feminine and vulnerable, glancing to her right with a wistful expression. Her work is almost entirely devoted to lovingly sensuous and almost yearning pastels of the female nude: here The model disrobing (1917), from the Art Gallery of NSW collection, is typical, contrasting the creamy skin of the girl with the deep black of the background.

One of the most talented artists in the exhibition is Jessie Traill (1881-1967), another daughter of an upper-middle-class family who was educated in Switzerland and spoke several languages, still today a relatively unusual thing for Australians, who tend to be lazy about language learning. Here, because the emphasis is on Europe and especially Paris, Traill is represented by a very early and a late work, fine pieces in themselves but not as outstanding as her masterpieces, the series on the building of the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

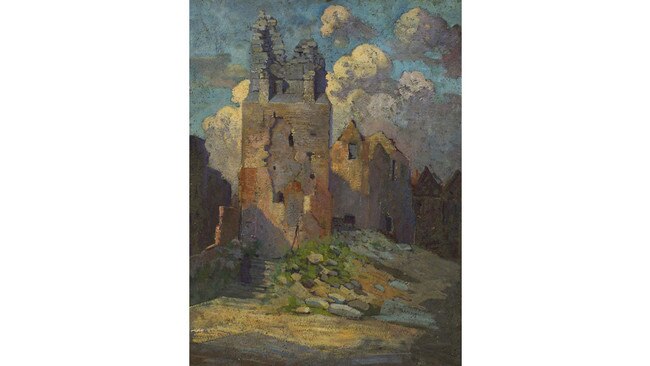

Another interesting artist is Evelyn Chapman (1888-1961) who, unlike the others discussed so far, married and had a daughter who recently bequeathed a large corpus of her mother’s work to the AGNSW. Chapman is particularly noted for her paintings of the battlefields of World War I, which she was the first female artist to depict. Here she is represented by two pictures of a ruined church at Villers-Bretonneux, but also by a large academic study of a female nude in charcoal, which reminds us that she too, like Goodsir, Cumbrae Stewart and Traill, had received a solid foundation in the techniques of painting.

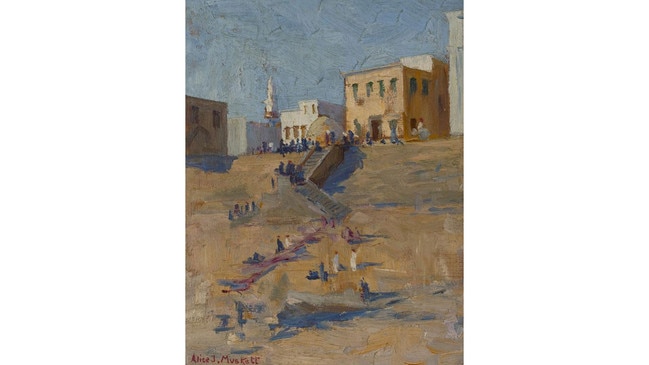

This was not the case for all the women in this exhibition, however. The most extreme contrast is between two artists who are today almost completely unknown, Anne Alison Greene (1878-1954), with three views of Paris, and Alice Muskett (1869-1936), with two small oil sketches of the Nile. Greene was from Queensland and later lived in Paris for most of the rest of her life. But her work is amorphous and bland, with little understanding of tonal structure or of chromatic range.

Muskett, on the other hand, was an early pupil of Julian Ashton, who made three portraits of her. She studied at the Academie Colarossi in Paris in 1895-98 and seems to have lived between Europe and Sydney for a couple of decades, for she shared a house in Sydney with her older brother, also unmarried, until his death after a nervous breakdown in 1909.

Philip Muskett (1857-1909) was indeed also a very interesting man, a medical practitioner with a special interest in diet. In 1893 he published The Art of Living in Australia, in which he advocates adapting our diet to the realities of a more Mediterranean climate, including eating more vegetables, salads and olive oil, instead of persisting with heavy English food, and in 1898 he published The Book of Diet. Another major work was The Illustrated Australian Medical Guide (1903 and 1909).

Alice, for her part, was also the author of short stories and a semi-autobiographical novel, Among the reeds (1936). The two small paintings by her are among the most intriguing in the whole exhibition. They are clearly plein-air studies, both made in 1911, after Philip’s death, during what must have been a Nile cruise like the one immortalised by Agatha Christie in Death on the Nile (1937). The economy with which she has been able to capture both tonal structure and colour in a study from life are evidence of the kind of foundational skills Greene seems never to have learned.

Several better-known artists were relatively deficient in these skills, which can leave their work feeling disappointingly weak. Ethel Carrick (1872-1952), among the best of them, is an appealing artist and yet ultimately a very minor one. Her pictures here, of nannies with prams in the Jardin du Luxembourg or flower markets in Nice, are lively and bright, but lack a mastery of spatial structure.

Kathleen O’Connor (1876-1968) was another talented artist, but there is something a little shapeless about her painting that reflects, as with all the later painters who imitated French impressionism — as distinct from the original local style of the Heidelberg School — a misunderstanding of its principles, for the greatest impressionist painting is underpinned by an instinctive feeling for tonal structure.

A little later, a number of artists such as Grace Crowley (1890-1979) set off for France between the wars and learned academic and formulaic versions of modernist styles such as cubism. The results can be pleasing at times, but are inherently limited because of the failure to learn the art of painting properly from the ground up. Consequently such artists are prone to mannerism, as we see in Crowley’s Figure Study (1928-29), in which facile tricks constantly get in the way of real observation.

Crowley’s untitled landscape study of Mirmande, where she was studying with Andre Lhote, is more satisfying, but her Study for Sailors and models, also from 1928, is once again an example of academic cubism. These pictures epitomise the almost universal problem at modern art schools, where students are able to produce presentable work within specific parameters laid down for them, and pastiches of their teachers’ styles, but are not equipped with the full range of skills to become autonomous practitioners of their art.

One of the worst cases of poor teaching is Moya Dyring, friend of David Strachan, who later set up a studio in Paris in her name, but whose pictures are feeble and mannered. Returning to a question implicitly raised by the fact that so many of the artists discussed here were lesbians, we could reflect that all art involves a balance of the yin and yang, feminine and masculine sensibilities, regardless of the sex of the individual. But this is not just a matter of innate qualities: for while spontaneous aesthetic receptivity belongs to the yin, the structural and compositional strength of the yang is developed only by serious training.

Intrepid women.

SH Ervin Gallery, Sydney. Until March 11.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout