Pierre Bonnard, Marthe de Meligny were young, in love and no prudes

French artist Pierre Bonnard and his muse weren’t rich, but lived their life the way they wanted to, as a new exhibition which has been several years coming shows.

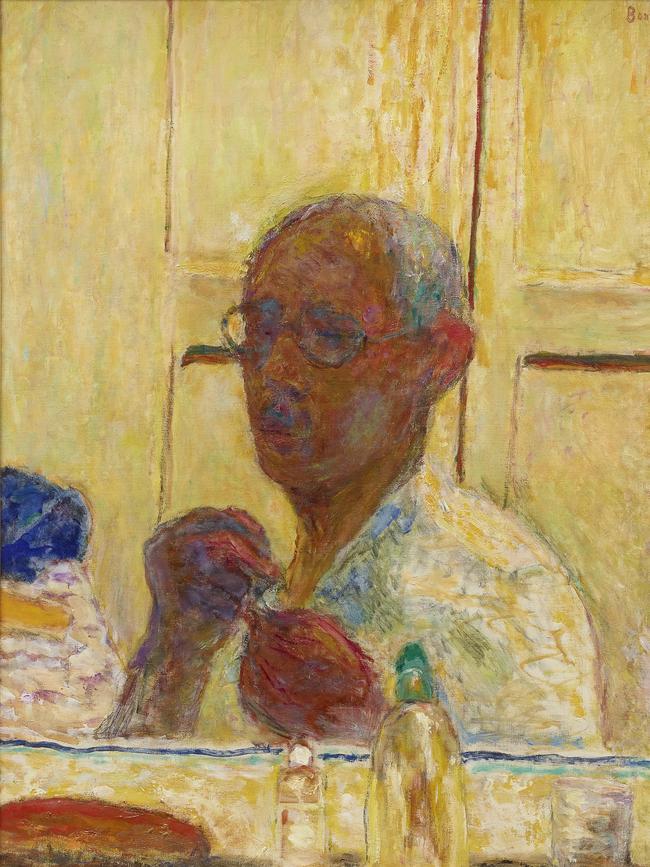

If you have not already met Pierre Bonnard, perhaps it’s time you were introduced. He really is the most companionable, gently witty and amusing of artists. His paintings – interiors, nudes, landscapes – are wonders of colour and light that radiate an irresistible joie de vivre.

Take a painting such as his Dining Room in the Country, 1913, from the Minneapolis Institute of Art. The doors and windows are flung open. Bonnard’s wife, Marthe, leans in through the window. A cat sits up on an armchair. The table is set with dinner things, the white cloth a contrast to the vivid orange wall behind. The miracle of the picture is the merging of indoors and outdoors as an “interior landscape”. As in paintings by Matisse, the bright colours and harmony of elements tell you everything you need to know about Bonnard’s happy disposition.

A major exhibition of the French artist, who died in 1947, is coming to the National Gallery of Victoria. More than 100 works by Bonnard and others by his contemporaries – paintings, works on paper, poster art, photographs and film – are part of the long-awaited show, delayed for three years because of the pandemic.

Bonnard is very much a painter’s painter. Margaret Olley, for one, was immensely fond of him. If you listen you can almost hear her saying his name, a smoky aspiration on the second syllable. William Robinson is also a fan. It would be quite interesting, in fact, to put some of Bonnard’s interiors side-by-side with Robinson’s – they speak a similar language of intimacy and contentment. And they share a kind of whimsical, playful humour, an appreciation that the small details of life can also be the source of the greatest pleasure.

Bonnard is of course famous for these intimate interiors, but it was only one aspect of his output. Less known are his ventures with graphic design, photography and even the performing arts. Early in his career, Bonnard had the good fortune to receive a commission to design a poster advertisement for champagne. He turned it into a work of wonder – a young woman in a yellow dress holds a fan and a glass of champagne, the bubbles frothing and overflowing. Neither the poster format nor the lithographic process were new, but the way he approached the subject and medium were an innovation as he combined the bold and simplified outlines of Japanese prints with a reduced colour scheme of pink, yellow and pinkish-yellow.

When the posters went up around Paris in the summer of 1891 they caused a sensation. For the art critic Felix Feneon, the colour and esprit of Bonnard’s poster made him feel that he was on holiday. Another admirer was the impish young artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. “Take me to your printmaker,” he begged of Bonnard. Toulouse-Lautrec took on the techniques of Bonnard’s lithographer Edward Ancourt, and was on the way to producing his own startlingly original posters of the Moulin Rouge.

“Really, without Bonnard and that champagne poster, there would be no Toulouse-Lautrec,” says Tedd Gott, the NGV’s senior curator of international art and our guide through this introduction to the artist.

“Imagine what the poster must have looked like in 1891 when it first hit the streets of Paris. Many people would have had trouble reading it, because it’s so abstract and deliberately anti-representational. But once you get your head around what the lines are doing, you then see the frothing champagne and the elegant lady getting tiddly on it.”

The point, Gott says, is that Bonnard was an artistic innovator, or at least an early adopter, of new techniques and ideas, including printmaking and photography. Some of his early paintings in Paris have the frozen-image quality of a frame of cinematography, such as The Cab Horse, 1895. He was friendly with the motion-picture pioneers August and Louis Lumiere, two of whose experimental early films will be shown in the exhibition.

The champagne poster was meaningful to Bonnard for another reason. His fee for the commission finally gave him a feeling of financial independence from his family, and vindication that his chosen path to be an artist was the right one.

He was born in the southern suburbs of Paris, in October 1867. His father was a senior official in the Ministry of War, and had decided that young Pierre on his graduation from the lycee would enrol in the law school of the University of Paris. Henri Matisse, who would become a good friend, was a near contemporary, being born two years after Bonnard and also intended for a career in law.

Bonnard was well into his legal studies when he started taking art classes at the Academie Julian. There, he fell in with a group of other young men, including Paul Serusier, who set up their own artistic movement, the Nabis, taking their name from the Hebrew word for prophet. After his graduation from law school he was accepted into the Ecole de Beaux-Arts and met two other artistic friends, Ker-Xavier Roussel and Edouard Vuillard.

Gott sets the scene, with Vuillard, Maurice Denis and ambitious impresario Aurelien Lugne-Poe moving into digs together in Pigalle. They pinned their prized Japanese prints to the walls, like the Blu-Tacked posters of later generations of students. You can hear their high spirits as Bonnard shows his paintings with his friends the Nabis at Le Barc de Boutteville, and as his champagne posters start to appear around Paris.

And imagine the fun when Lugne-Poe starts to put on his shows under the banner Theatre de l’Oeuvre including, in December 1896, the notorious Ubu Roi, by Alfred Jarry. Bonnard helped design the sets for the show – and, later, puppets – in which King Ubu is a kind of comic grotesque not unlike, Gott suggests, Sir Les Patterson.

“There are only two performances of Ubu Roi: the dress rehearsal and the opening night – which is also closing night,” he says. “It is immediately banned on the grounds of obscenity, corruption and immorality. It’s the first time that someone yells ‘shit!’ on stage. You have beheadings and poo jokes. On both nights it’s a riot with whistling and catcalls and throwing chairs at the stage. But it becomes a thing.”

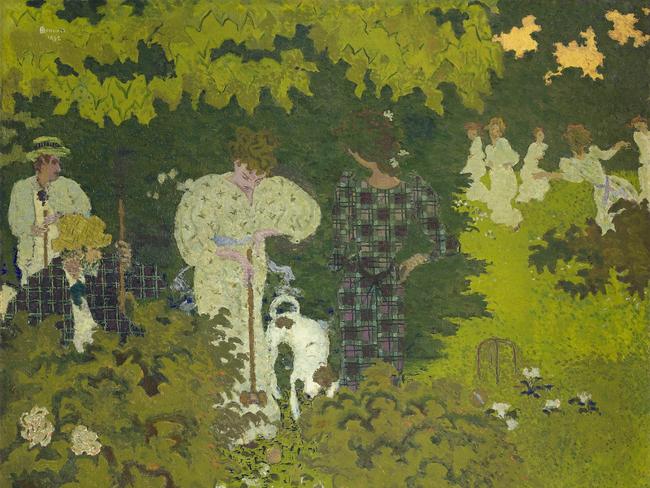

The Nabis as a group were characterised by their love of colour and pattern – sometimes the more mixed-up the better. From Gauguin they took the idea of strong blocks of vivid colour, and from Japanese prints they adapted the treatment of two-dimensional space. Bonnard, in particular, stuck with the manner of pictorial flatness that would become such a feature of modern art in the near-next century. Not for nothing was he known among the Nabis as “Le plus japonard”, the most Japanese.

“The Nabis turned around the landscape view of the Impressionists, and instead of trying to cut a window through a wall and look out – which is what a Monet landscape looks like – they emphasise the flatness of the wall itself,” Gott says. “They are not trying to create a three-dimensional illusion … Their paintings are about decoration, not about cutting a window to look out on to nature in the Impressionist mode.”

To say the Nabis’s work was decorative is not to diminish it, and its ornamental character will be emphasised in the NGV exhibition. The gallery rooms have been decorated by interior designer India Mahdavi, using the bold colour and patterned wallpapers that were a feature of Bonnard’s and the Nabis’s paintings.

“Monsieur Bonnard and I share the same passion for colour, the way he invites us in his home and intimacy is sublimated by his very own sense of colour,” Mahdavi says. “For this exhibition, we dived into Pierre Bonnard’s paintings and extracted some of his patterns and colours to recreate backdrops to his paintings, offering an immersive experience of a home to the visitor.”

Bonnard’s treatment of the nude is worth discussing because it says so much about his approach to painting. In 1893 he met a young woman, Maria Boursin – she preferred to be known as Marthe de Meligny – who became his model, muse and life partner. They lived together for many years, Marthe eventually calling herself Mme Bonnard, but did not actually marry until 1925.

Marthe appears in Bonnard’s paintings as a subject and sometimes as an anonymous figure, and adds immeasurably to their charm and intimacy. As a couple, they were frank about nudity: both appear naked in snapshot photos in the exhibition. And, unusually, Bonnard depicts himself full-frontal with Marthe in the painting Man and Woman, of 1900. They were not prudes.

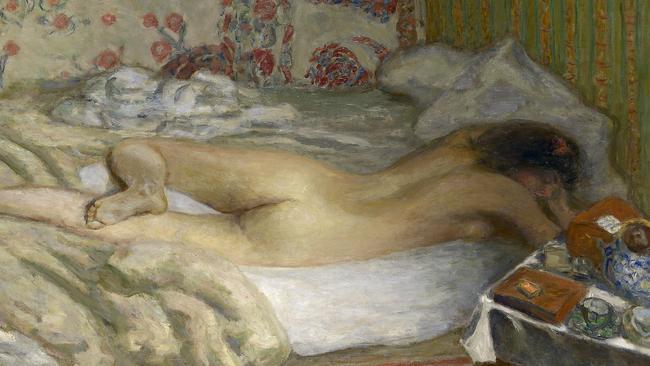

A neighbouring work in the exhibition is Siesta, 1900, from the NGV’s own collection. An important painting in Bonnard’s output, it has a fascinating provenance, being once owned by those great patrons of early modernism, Gertrude and Leo Stein, and later by the former director of Britain’s National Gallery, Kenneth Clark. It entered the NGV when acquired by the Felton Bequest in 1949.

Siesta shows Marthe lying on a bed, face down, her bottom turned towards the viewer. The pose is similar, Gott notes, to that of the Sleeping Hermaphroditus in the Louvre. And there’s a feeling that you’ve just walked in on her, dozing after she and Bonnard have had sex. These are two young people in love, not rich, but living their life the way they want to.

Gott says the painting is a transitional work for Bonnard as he started to break away from the Nabis – the group ended their formal association in 1900 – and establish himself as an independent artist. It’s the reason the painting is often requested for international exhibitions of Bonnard’s work.

“He’s had his first painting show in 1896, and it’s quite successful, but he’s still poor – he doesn’t want to use his dad’s money,” Gott says. “So he and Marthe are living in this little flat near the Place Clichy at the base of Montmartre. They can eat but they’re not rolling in money, and the painting reflects that. They probably have to climb up six flights of stairs, and there’s this squalid little apartment with the mattress just straight on the carpet. It has this combination of exoticism and shabby chic.”

Another feature of Bonnard’s pictures of Marthe is that she did not always pose for him in a formal sense. Bonnard painted not directly from life, but from memory, drawing on his sensations of light, colour and form, and working up the pictures in his studio.

“She poses for him and even when she is not posing for him, she is posing for him,” Gott says. “So she pops up in a lot of the Nabis works as a kind of background character.

“Siesta is the first painting in which he is showing their physical relationship. These are young people in Paris – they are not only liberated in their desire to not do Impressionist landscapes, they are also sexually liberated. Bonnard and Marthe live together openly, they are pushing the envelope of permissibility.”

Bonnard first visited Monet at the artist’s beautiful home and garden in Giverny in 1909, and he and Marthe bought a house in Vernon, not far from Monet. It’s where he painted Dining Room in the Country, described earlier. He remained friendly with the older artist until his death in 1926, as Monet with his failing eyesight needed the assistance of younger “eyes” like Bonnard’s.

By this time, Bonnard and Marthe had fallen in love with the beauty and lifestyle of the south of France. Eventually they moved to Le Cannet, a village just to the north of Cannes, and struck up a friendship with Matisse, who lived not far away in Nice. Much as Matisse had a friendly rivalry with Picasso, he had a similar relationship with Bonnard. Each artist would always keep a painting by the other in their studio.

It sounds like a cliche, but Gott assures it’s true, that Bonnard’s palette brightened considerably with the move to the Riviera. He had a characteristic way of working, not putting his stretched canvases on an easel but pinning the cut canvas to a wall, and working on several paintings simultaneously. When he and Marthe wanted to travel, he’d simply roll up the canvases and take them with him.

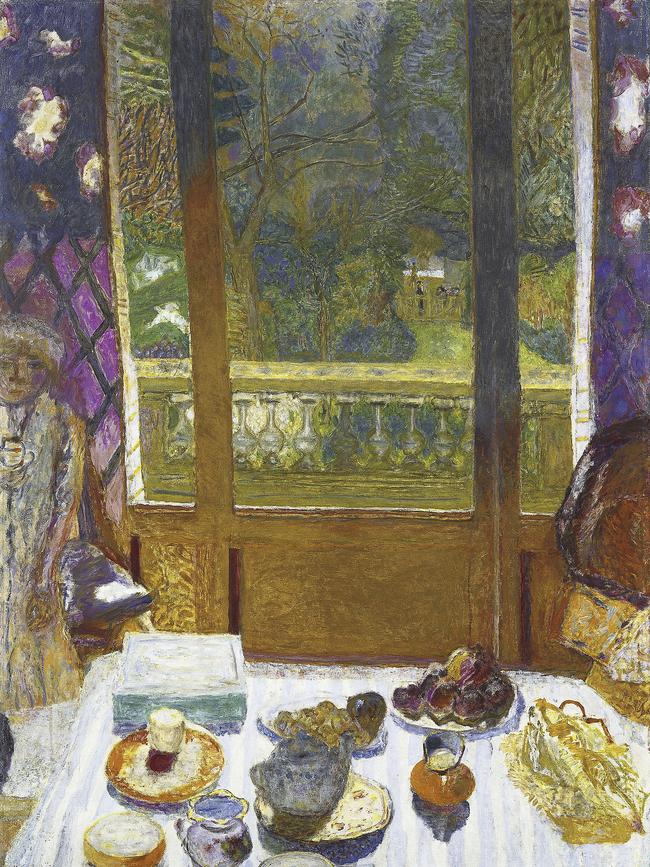

The decades from the 1920s are when Bonnard produced some of his loveliest works. Light saturates his White Interior, painted in Le Cannet in 1932. It shows a corner of a dining table, with a teapot, cups and a vase of flowers. The glowing red-orange sky and the Mediterranean can be seen in the distance through the open French doors. Marthe is leaning under the table, and appears to be reaching out for the cat. But it’s a painting with no definitive subject. All is light, colour and atmosphere.

“Bonnard invents something that’s really quite new,” Gott says. “The paintings are at once an interior view, and then through the window or door, you have an extensive landscape view. In the interior you have an amazing still life section, like its own little painting within a painting. And, usually, you will find Marthe, maybe bending under a table, and a dog or a cat. And the elements are not done naturalistically.”

Curated by the Musee d’Orsay in partnership with the NGV, and with loans from the Paris museum and other international collections, the exhibition has more than 100 works by Bonnard and paintings by his contemporaries Denis, Vuillard and Felix Vallotton, as well as films by the Lumiere brothers.

“This is the first full retrospective in Australia, with every media and every aspect of his career represented,” Gott says. “And marrying it with the design by India Mahdavi is a brilliant decision on the gallery’s part – it creates the excitement of what it must have been like for Parisians to come across these young people working with these beautiful new patterns and colours in the 1890s.”

This splendid Bonnard show has been several years coming. First programmed for winter of 2020, it was postponed because of the pandemic. Fortunately, the lenders of art works in the exhibition – from the Orsay to the Tate in London, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York – have been happy to again make their pictures available, three years later than planned. If you haven’t yet made an acquaintance with Bonnard, or already know the pleasure of his company, now is the perfect time.

Pierre Bonnard: Designed by India Mahdavi is at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, June 9-October 8.